Reading Emmanuel Carrère’s 2011 memoir of the late Russian opposition politician and writer, Eduard Limonov, I was struck by this line: “Cliche has it that poets in Russia are as popular as singers in the west, and like many cliches about Russia, it is, or at least was, absolutely true.” Which begs the question: was it true because of something intrinsic to Russia and Russians, or to poetry?

My stepmother, who was half-Russian, had an annoying tendency to go on about the Russian “soul” – a figuration of Russian identity as purer, more lyrical, and closer therefore to the godly than the benighted west. Owing its origins to the great Russian writers of the 19th century, by the time the Soviet regime really got into the repressive swing of things, the notion seemed worse than obsolete – a wilted fig leaf, ill-concealing the party’s zeal for rapine, torture and murder.

Yet it was precisely during the Soviet era that Russian poets fully realised the cliche: the likes of Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Anna Akhmatova and Joseph Brodsky were indeed regarded by their contemporary readers with the awe now reserved for rock stars. When their verses were permitted, any sort of official publication they wrote sold out in vast editions in a few hours – while when fully repressed, they entered the collective consciousness via memory and repetition, or through being copied and recopied, over and over again, then clandestinely circulated.

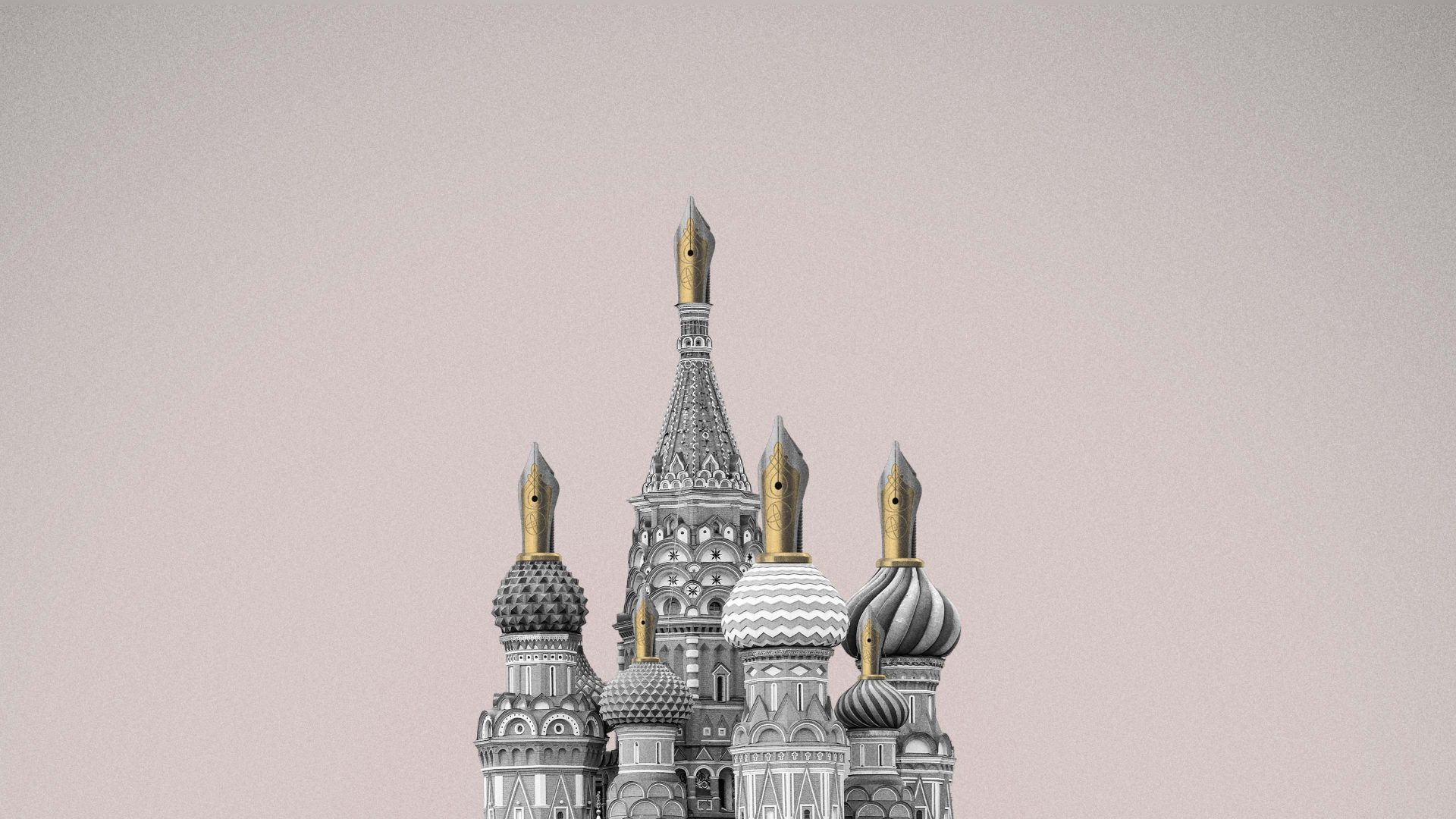

When you consider it, this form of publication – “samizdat”, literally “self-publishing” – is a far more truthful register of literary significance than anything practised in the west; for, in order for your priceless prosody (or peerless prose), to reach readers, those readers themselves had to become your publishers. This makes samizdat the complete inversion of self-publishing in the west, which is less literature than an opportunistic crime committed by vanity and money working in cahoots.

Reproductive technology and political repression are surely both bound up in poetry being popular – in Soviet Russia it was hand-copying, but in the England of the early 1800s, mechanised printing had yet to advance to the point where it was easy to print large runs of extensive prose texts. Lyric and epic poems, ballads and even epithalamiums were the order of the day – while Lord Byron’s scandalous behaviour made him a sort of Regency dissident, raging against the hypocrisy of sexual repression, the way Akhmatova et al were to against political repression.

Published in 1812, Byron’s Childe Harold sold 500 quarto copies in the first three days of publication – and there were numerous and rapid reprints. Byron went pretty much overnight from obscurity to notoriety, and became the first true literary celebrity – at least, in the English-speaking world. But if the inception of offset printing combined with loosening morals led to the eclipse of poetry in the west; in the east, the need for ideas and impressions to be conveyed in a compressed and easily-remembered format meant that poetry remained paramount.

After all, what can be said of the Russian soul save that it’s received such a kicking from the Russian body over the years that it’s become either punch-drunk – stomping all over the place, and crushing everything in its path – or wholly traumatised and so dissociated from the body-politic. Under such circumstances the instrumentality of language naturally becomes suspect – what are novels, if not instruction manuals for social realities? – so its figurative capabilities come to the fore.

Whether or not this poetic predisposition has survived into the Putin era, I’ve no idea – but if not, it’s surely only that the plethora of available methods of publication mean readers no longer have to commit to its comprehension – let alone reproduction. After all, why trouble with the terza rima when you can post on Telegram or Tik-Tok instead? Here in the land of mists and mellow fruitfulness, apart from the obligatory obeisance to the idea that we’re so steeped in poetry – look at how the language of Shakespeare/the King James Bible/Carol Ann Duffy (delete as appropriate) percolates our own! – we don’t actually need to pay any attention to it whatsoever.

Consider the lamentable lucubrations of our latest official poetaster on the occasion of our beloved sovereign’s coronation. With “An Unexpected Guest” Simon Armitage condenses every twee image of the little people lovin’ it (“it” being the McMonarchy™), that you could wish for. Meanwhile, the nation’s real Poet Laureate, Adele, continues her residency at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, a venue that for sheer dictatorial vulgarity is surely on a par with Vladimir Putin’s palace at Cape Idokopas on the Black Sea.