Months before Britain’s rift with China widened over cyberattacks on parliamentary critics of Beijing came a sign that Europe was disentangling itself from links with the People’s Republic.

When world leaders converged on Beijing in October last year to celebrate the tenth anniversary of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), representation from the “collective west” was thin on the ground.

Six heads of state or government from the EU had attended previous iterations of the Belt and Road Forum – a talking shop for the global infrastructure and diplomacy strategy in which untold billions would flow from China in return for the recognition due an aspirant superpower. But this time, only China’s diehard ally in Europe, Hungary’s Viktor Orban, was able to make it.

The other notable attendees included Russian president Vladimir Putin, regarded in many of the 155 countries signed up to BRI as a pariah for his invasion of Ukraine, plus Turkmenistan’s “national leader” Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow and the Taliban commerce minister, Haji Nooruddin Aziz.

The recent forum was also notable for coinciding with the first-ever departure of a country from what Beijing calls its “Belt and Road family.” After almost a year of speculation, and just months after the Taliban officially petitioned to join, Italy sent its withdrawal request.

But Europe’s relationship with the BRI wasn’t always so cold. In the years following the initiative’s launch in 2013, when Europe was still reeling from the Global Financial Crisis, everyone was looking East for salvation.

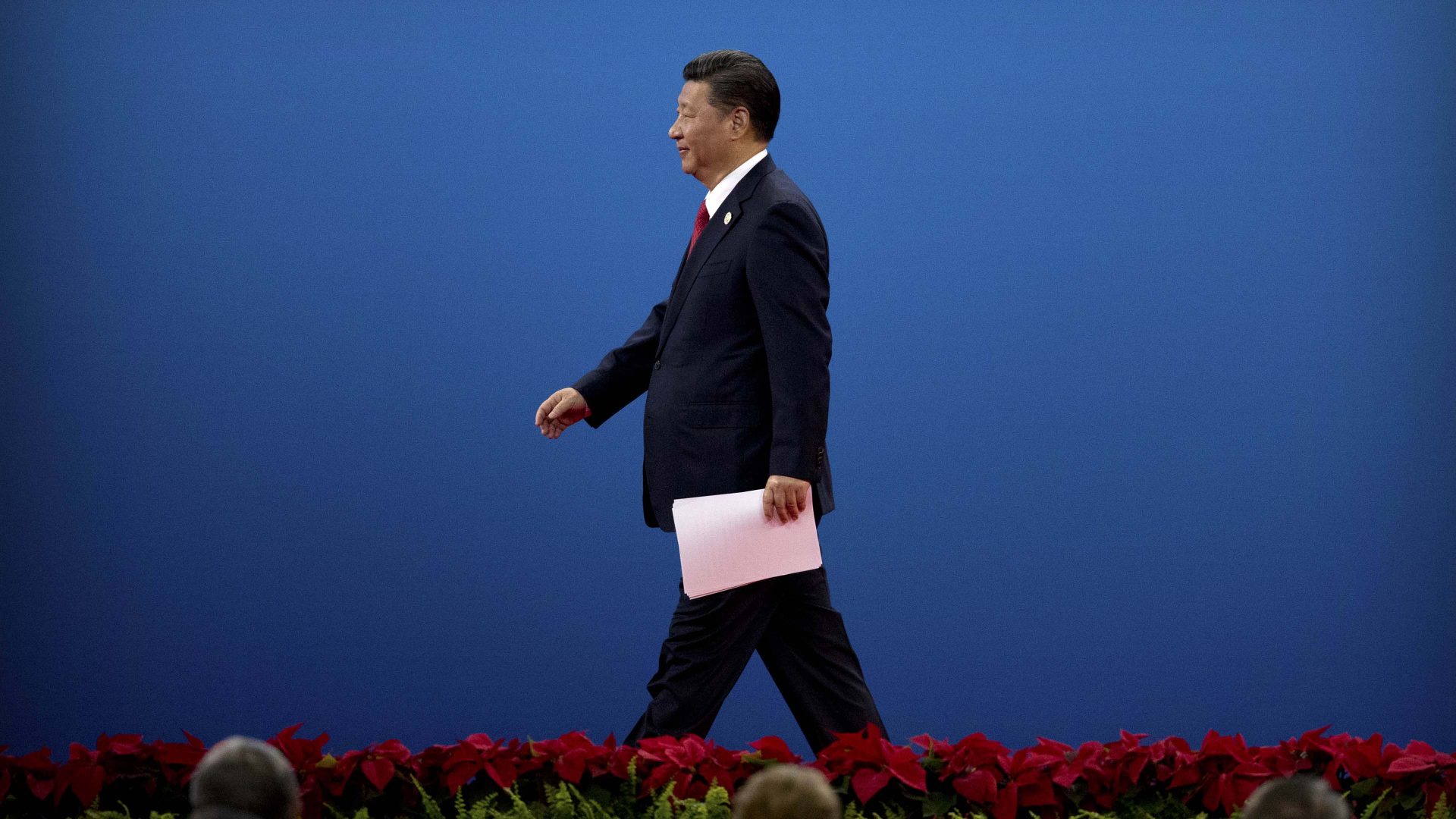

The BRI was officially launched on September 7, 2013, when the newly anointed general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping, stood behind a dark brown, varnished lectern at Nazarbayev University in the capital of Kazakhstan, and proposed the construction of a “Silk Road economic belt” across Eurasia. A month later in Jakarta, Xi put forward a “21st-century maritime Silk Road” while addressing the Indonesian parliament. Together, this continental “belt” and maritime “road” form the “Belt and Road Initiative.”

The BRI is vague, amorphous, and deeply conceptual. You can’t point to it on a map and there is no definition of what constitutes a BRI project. According to official documents, it encompasses every possible field of human endeavour, from sports exchanges, to atomic energy.

Geographically, its scope is limitless, reaching the Arctic and even outer space. The BRI is whatever Beijing calls the BRI. Rather than a concrete initiative, it is more akin to a brand – a brand for selling a world in which China takes centre stage.

But back in 2013, this was apparent to few Europeans. Reinhard Bütikofer, a member of the European Parliament who was also a leading figure in the EU’s turn against the BRI, says, “I saw a geopolitical dimension to the BRI, but in the beginning that feeling was little shared in Europe.”

The BRI arrived in Europe during the ongoing aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, at a time when politicians were betting on a Chinese future. In this age of optimism – some would say naivety – the United Kingdom under David Cameron was far from alone in pushing for a “golden era” in relations with China. Hungary became the first country to join the BRI in 2015, followed by Bulgaria, Czechia, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia that same year, with nine other member states joining in the years that followed.

The core idea behind the continental Silk Road Economic Belt contains a compelling physical dimension. It is about connecting East and West through the Eurasian heartland. It hinges on a narrative of revival, tying Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream” of national rejuvenation to a continental, Eurasian dream of new historical relevance.

As late as 2019, every official between Brussels and Beijing would speak about how they intended to harness EU-China trade to become a strategic hub along the New Silk Road. “I remember conversations in Poland about Chinese funding for the Central Communication Port, a major aerial logistics hub,” says Grzegorz Stec, a Brussels based analyst with the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). “For a lot of member states, the thinking was that this would be free money.”

When Italy signed up to the BRI, it did so with the same hope that its cash-strapped government could attract Chinese investment across a hugely ambitious range of sectors.

Political interest in the BRI was more muted in the West than in Central and Eastern Europe, but everywhere the business community was chomping at the bit. On the sidelines of Davos in 2018, the CEO of Siemens, claimed that the BRI would become the “new World Trade Organisation.”

Bütikofer recalls German business people being asked at a 2018 conference in Jakarta how many of them expected to gain from the BRI. “The overwhelming majority expected to benefit,” he says, “but when asked who had benefited already, the number was terribly low – here you see the gap between belief and reality regarding the BRI.”

Eventually, this gap between expectations and reality began closing. “A part of it is that China overplayed its hand,” says Stec, “the numbers it floated around and hopes it ignited through speeches and memorandums simply didn’t materialise.”

One reason those numbers didn’t materialise is because of how the BRI works. Beijing is now more careful about lending money, but in the BRI’s heyday, the average size of loan contracts was upwards of $300 million. The BRI was powered by Chinese financial firepower, wedded to Chinese engineering muscle. Throughout the 2010s, Chinese banks lent colossal sums of money for projects, few questions asked, providing the cash was paid to a Chinese contractor.

Countries outside the EU, like Serbia, have built many Chinese projects this way, but EU member states can’t simply hand out contracts for large projects without competitive bidding. Hungary is the only EU country that tried, but in doing so they triggered an EU inquiry.

Neither are the conditions for these loans especially fantastic. “EU member states are smart enough – Why ask for a loan when you can get EU funding for free?” says Dr Tamas Matura, Founder of the Central and Eastern European Center for Asian Studies.

When it was first launched, the BRI was a mirror for Europe’s dreams. Eventually, it began to dawn on policymakers that the BRI is first and foremost an engine for moving Chinese companies up global league tables.

Through BRI loans, Beijing subsidies Chinese companies while shifting the cost onto taxpayers in developing countries. It’s a good enough deal if you need a bridge built and can’t raise the funds, but it’s not the investment many in Europe were hoping for. Neither is there room in this China-centric constellation for Bütikofer’s German businesses – BRI contracts are handed out behind closed doors, and generally not to European companies.

When Italy decided to leave the BRI, it was in large part due to disappointment – Chinese investment actually declined from 2019 to 2020, while promises to transform Italian ports went nowhere.

Around the same time as Italy was signing up to the BRI, Brussels’ response to the initiative began changing, from cautious engagement to active competition. A new connectivity strategy was revealed in 2018, and this evolved into the Global Gateway, launched in 2021 as a more assertive response to the BRI.

According to Noah Barkin, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund, “the EU sensed in 2018 that the BRI was a challenge, but the bloc’s positioning was different – it denied that the Connectivity Strategy was a response to the BRI.” Since then, Barkin says, “the relationship has deteriorated and the EU is more comfortable naming China as the target.”

In 2019, the European Commission adopted a new framing for its relationship with China, labelling Beijing a “partner, competitor, and systemic rival.” The move was part of a general shift in Europe, away from what Bütikofer likes to call an era of “blue eyed self-deception” about China and towards a more cynical view of Chinese intentions.

It’s difficult to pinpoint an exact turning point in this journey – for some early adopters, the 2016 Chinese takeover of German robotics firm Kuka was a moment of awakening. For others, it took right up until the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and Beijing’s persistent support for Moscow.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen leads the pack when it comes to taking on China. During the past five years, there has been a tug-of-war over China policy between the European Commission and member states.

According to Barkin, “if you look hard enough, there are still those in Europe who would like to work with China as if the tensions of the past few years never happened,” yet he notes that the “political space to do that has shrunk significantly.”

No CEO of any major European company will again publicly declare the BRI a “wise and powerful force,” but this rhetorical shift might not reflect intentions in boardrooms and national capitals.

The BRI is just a branding exercise for Chinese economic power. Brussels has helped make this brand unfashionable in Europe, but Chinese power is still a reality. Facing economic stagnation and geopolitical turmoil, many would prefer a less antagonistic relationship with China, even at the cost of long-term security. In the event that Beijing invades Taiwan, dependence on China could prove catastrophic, but until that day, many European companies would rather make hay while the sun shines. If Ursula von der Leyen is still at the helm after the European Parliament election this year, she will have to continue dragging quietly resisting Europeans towards her vision of a more muscular, competitive relationship with China.