Even though he has not achieved it yet, it was there on the list of Rishi Sunak’s achievements in his first year as prime minister. “Smoke-free generation,” it said, referring to Sunak’s plan, now assailed by Conservative libertarians like Liz Truss, to legislate so children currently 14 and under will never be able to legally purchase tobacco products.

“The government should abandon its profoundly unconservative plans for the ban on tobacco sales to those born after 1st January 2009,” Truss wrote on social media last month, signalling the opening of yet another front in the Tory right’s war of attrition against Sunak. “A Conservative government should not be seeking to extend the nanny state. It only gives succour to those who wish to curtail freedom.”

Defenders of the Sunak strategy ignore all this and say that backing their bill will produce a healthier workforce and considerable savings to the NHS. That sounds good, but the prime minister does not deserve much credit for the idea – it is borrowed from Labour, who borrowed it from former New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern.

Then again, in the history of human interactions with tobacco, hardly anyone who has had anything to do with the plant has been able to step away with much credit.

I must count myself in that unfortunate company: the enthralling combination of vanity and addiction that had me smoking Gitanes, the soul-filling joy as the rasping smoke of brown tobacco hit the back of my throat while I prepared to fight off the jeunes filles en fleur who would surely come flocking around me as a direct result.

The crucial date in the history of plant and human interaction is 1492, when Christopher Columbus took his first voyage to the New World. This initiated the Columbian Exchange: wheat, cotton, rice, citrus fruits and bananas went to the Americas, while potatoes, tomatoes, maize and chillies came to Europe. Along with tobacco.

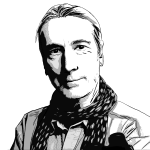

Tobacco creates nothing in us beyond the desire – the need – for more. This makes it the ideal trading commodity and also a rebuke to the idea that the power of market forces is universally beneficial. But perhaps the most fascinating thing of all about tobacco is that it is completely useless to humanity.

The energy for (almost) all life on Earth comes from the sun. But there is only one set of organisms capable of using that energy to make food, and that’s plants. Plants make the sun’s energy accessible to all other forms of life. Either we eat the plants, or we eat the plant-eaters (Plant-eaters include fungi, so mushrooms are more closely related to us than they are to tomatoes).

But plants don’t take this lying down. They have developed many ways to avoid getting eaten and as a result, their consumers have developed many ways of getting round these defences. Throughout millions of years of life on Earth, an arms race has continued between plants and plant-eaters.

Nettles sting, gorse is prickly, trees have bark, while some plants ingeniously employ insects as guardians. And other plants manufacture poisons; these make consumption unpleasant at best and lethal at worst. Among the most famous poisonous plants are the nightshade family, which has 2,700 species. These include deadly nightshade, potatoes, tomatoes, aubergines – and tobacco.

With the middle three of these, the plants can be made palatable by selecting which parts you eat and by preparing them properly. But the poison put out by tobacco plants – there are 70-odd species – is the whole point. Humans consume tobacco in order to get at the poison.

This poison was named for Jean Nicot, a 16th-century scholar, the French ambassador to Lisbon and a great promoter of the health-giving benefits of tobacco. Nicotine affects the muscle-response signal to the brain. “Let us take the air in a tobacco trance,” wrote TS Eliot, another enthusiastic smoker. In sufficient doses nicotine causes constant muscular contractions that lead to paralysis and death.

Tobacco was used in the pre-Columbian Americas in religious ceremonies, as a painkiller, as a trading item and even as currency. Its use in Cuba was described by Bartolomé de las Casas, priest and historian, in 1502: “I knew Spaniards on this island of Española who were accustomed to take it, and being reprimanded for it, by telling them it was a vice, they replied that they were unable to cease using it. I do not know what relief or benefit they found in it.”

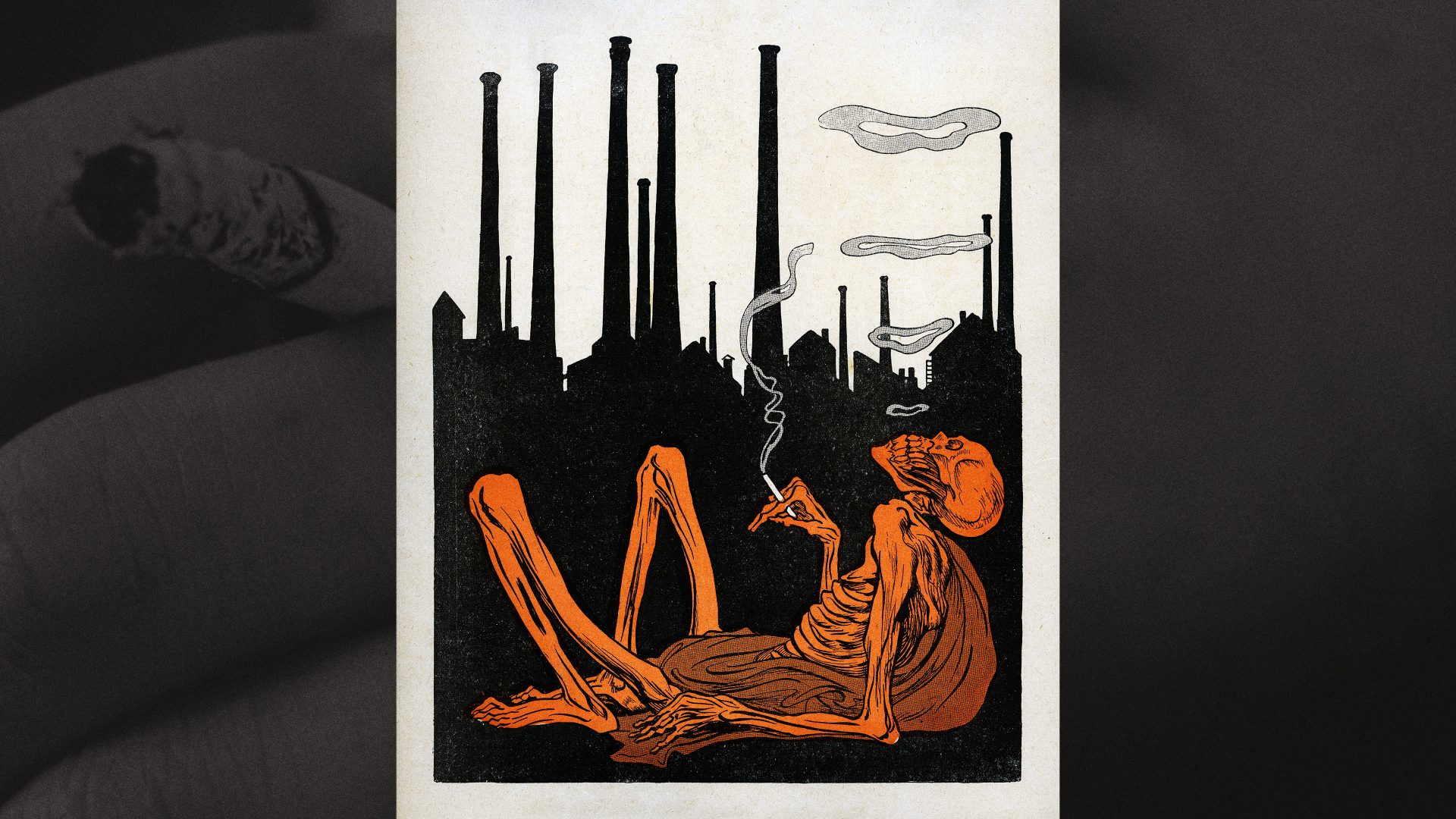

Tobacco crossed the Atlantic and became rather a hit: “All they that love not tobacco and boys are fools,” wrote Christopher Marlowe. Only that natural contrarian, James I, was against it, and published A Counterblaste to Tobacco in 1604.

So let’s go back to market forces. There was a growing market for tobacco, notably in Europe, and plenty of people eager to supply it on the far side of the Atlantic. The only problem was that producing smokable tobacco was not a straightforward business. It is difficult work and highly labour-intensive. It requires cultivation, harvest and then, crucially, curing: the leaves must be dried, but not allowed to dry out. Those who used indentured labour found it almost impossible to turn a profit.

But if your labour was free, profits were easy. In 1619, 20 African slaves were brought to Virginia and a profitable trade in tobacco was established at last. The world has been feeling the repercussions ever since.

Tobacco could be smoked in pipes, or rolled in leaves as cigars. It could be chewed, it could be taken as snuff or as snus – a moist powder placed between gum and lip, while the sweepings could be rolled up in paper and smoked as a cigarette. In 1881 James Bonsack invented a machine to do the rolling and at once cigarettes were the easiest way of consuming tobacco. “A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure,” said Oscar Wilde. “It is exquisite, and it leaves you unsatisfied.”

What followed was a kind of golden age of tobacco, a time when smoking was not so much accepted as expected. What’s more, it was sophisticated, glamorous, elegant and altogether aspirational. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers looked almost as graceful smoking as they did dancing. Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall looked tough and stylish as the frail stalks of their cigarette smoke entwined. And could anything be more enchanting than Audrey Hepburn with her two-foot-long cigarette holder in Breakfast at Tiffany’s?

Cigarettes were everywhere, and cigarette smoke was an inescapable part of everyone’s environment. On the back of Bill Bryson’s child memoir of the 50s, The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, the blurb reads: “It was a happy time, when almost everything was good for you, including DDT, cigarettes and nuclear fallout.”

Matthew Engel’s excellent The Reign reports: “People smoked everywhere, including the non-smoking portions of trains… The non-smoking compartments were clearly marked, but the etiquette was that you could smoke in them if no one objected. It was polite to ask, “Anyone mind if I smoke?” Silence was deemed to convey consent. The answer ‘Yes, I do mind’ was considered most unsporting.”

Smoking was also permitted on the top deck on buses: “Found my way upstairs and had a smoke,” sings Paul McCartney in the middle section of

A Day in the Life, recalling the 82 bus he took to school. A friend of mine who did national service in the navy was issued with 600 cigarettes a month. When Brendan Behan won the essay prize at borstal, as he reports in his memoir Borstal Boy, his prize was 100 Players.

The first people to take against smoking were the Nazis, who taxed tobacco heavily and forbade smoking in public. Even in the 1950s, there were vague notions that smoking wasn’t entirely beneficial: older readers will remember adverts like “For your throat’s sake smoke Craven A”; a slang term for cigarettes was “coffin nails”. The first studies of the possible health damage from smoking came in 1948 under the British physician Richard Doll; a connection between smoking and cancer was established two years later. In 1964 the surgeon general of the United States, Luther Terry, published a report, Smoking and Health.

The response of the tobacco industry was not an instant refusal to continue selling tobacco. Instead, they fought tooth and (coffin) nail for survival. Kent cigarettes stressed the power and effectiveness of their “micronite filter”; which contained asbestos. An advertisement on US TV claimed, in a famous and cleverly ambiguous slogan, that “more doctors smoke Camel than any other cigarette”, and it can be found on YouTube; a white-coated doctor enjoying a fag (they didn’t call it that in America) between patients.

The cover-ups and denials of the links between tobacco and cancer within the tobacco industry can be instructively compared with the response to climate change by the Big Oil companies. And when campaigns of ridicule and discrediting failed they turned their attention to new markets – women and the developing world.

Virginia Slims was a brand for women. As a marketing ploy of genius, they attached their name and their cash to the rising women’s tennis circuit, playing a small but significant role in the development of feminism.

While tobacco companies fought bans on advertising and sponsorship and the introduction of health warnings on cigarette packets, they also turned to less-developed countries with less-developed tobacco laws. When I was in Hong Kong in the late 70s, there was an advert for Viceroy Super Longs. It showed a white-suited Chinese man leaning on the taffrail of a yacht, a blonde girl in the background. “Everything I have I’ve earned. Success in America. The yacht. The right to smoke the cigarette I choose…”

And smokers still have the right to smoke the cigarette they choose – for now, at least. The pariah status of today’s smoker has become a perverse attraction: there are times when I wish I was part of that freemasonry, standing in doorways, offering lights, exchanging laconic comments on what’s happening inside, being part of the brother-and-sisterhood of self-destruction.

And there’s another kind of pleasure involved as well: a sort of “fuck you, I’m a smoker. You got a problem with that? You want to get in the way of my pleasures? I have a libertarian right to poison myself and by implication poison the air all around me. If you don’t like that go and breathe some other air.”

The lingering libertarian principles that Liz Truss defends – that allow tobacco to remain on sale, and that are opposed to education, discouragement and legislation against tobacco smoking – are doing one thing: dumping the problem on the NHS. As if that hard-pressed organisation didn’t have enough problems.

Perhaps this is one rare occasion when Rishi Sunak has actually made the right call.