Because he was Jewish, in 1942 Curt Bloch was forced into hiding in the Dutch city of Enschede, to escape Nazi persecution.

Conditions in his hiding space were cramped and uncomfortable – and also boring. Bloch needed something to do. So he set up a magazine.

The Dutch word for “going into hiding” is onderduiken, meaning “to dive under”, and as a play on that meaning he gave his magazine the title Het Onderwater Cabaret, or The Underwater Cabaret. Between the summer of 1943 and April 1945, Bloch produced 96 issues of his magazine containing poems written in both Dutch and German.

Het Onderwater Cabaret

Those poems, with titles such as Yes, Yes Commissioner Sir!, Proposal to Dr Goebbels and German Cultural life in 1944 were bitingly satirical, attacking Nazi propaganda and Dutch collaborators, and ruminating on the life of someone forced into hiding. In They both look very sour, a poem about a newspaper photograph of Hitler and Goebbels, Bloch writes:

They both look very sour indeed,

I can understand it well,

They know their days are numbered,

No wonder they’re wetting their pants.

Elsewhere he deals with the terrible fate of his family. In a poem dedicated to his mother and sister he writes:

I am in a terrible bind

A fearful son and brother.

I do not hear from you two any more,

Where you are…

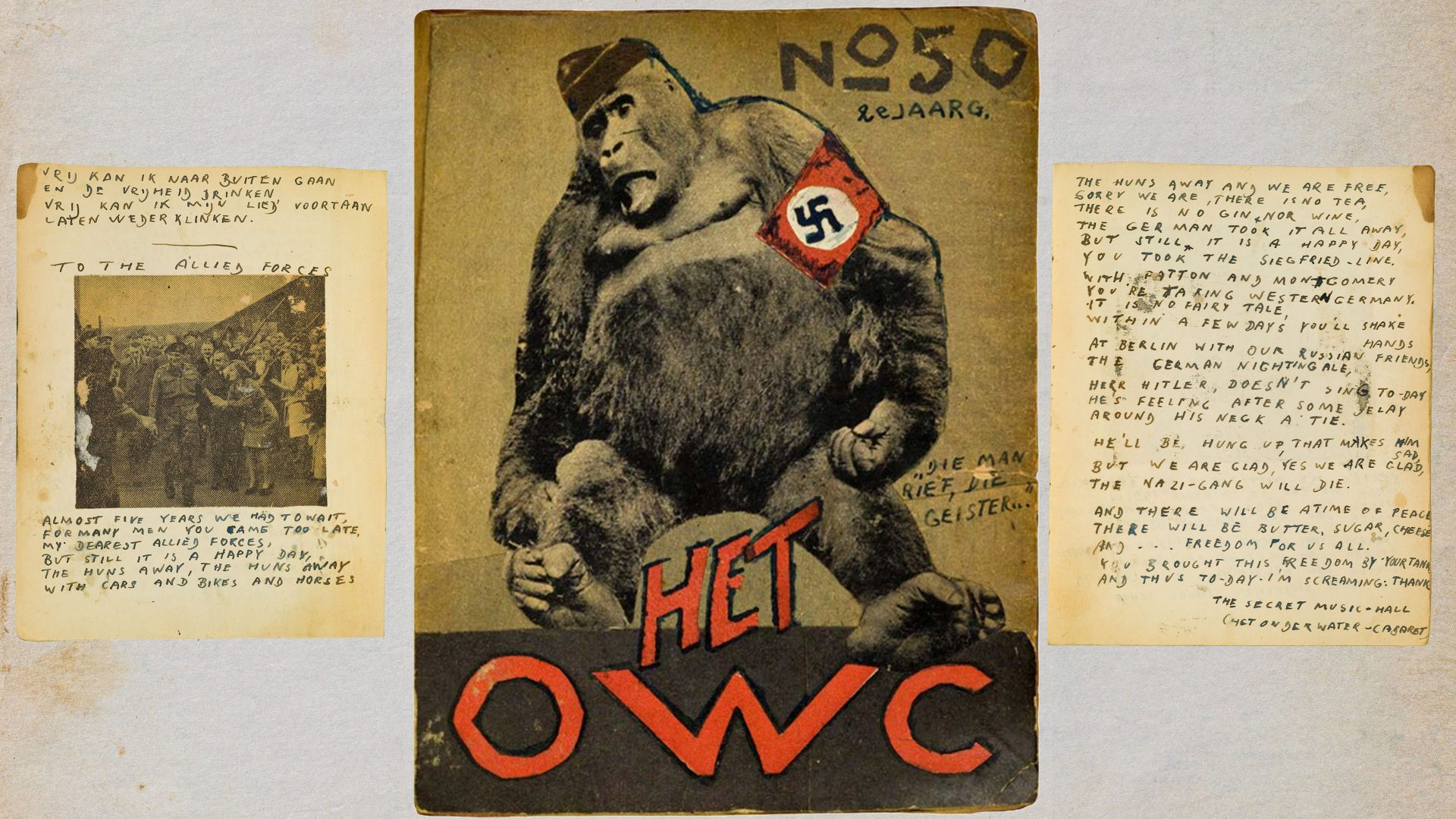

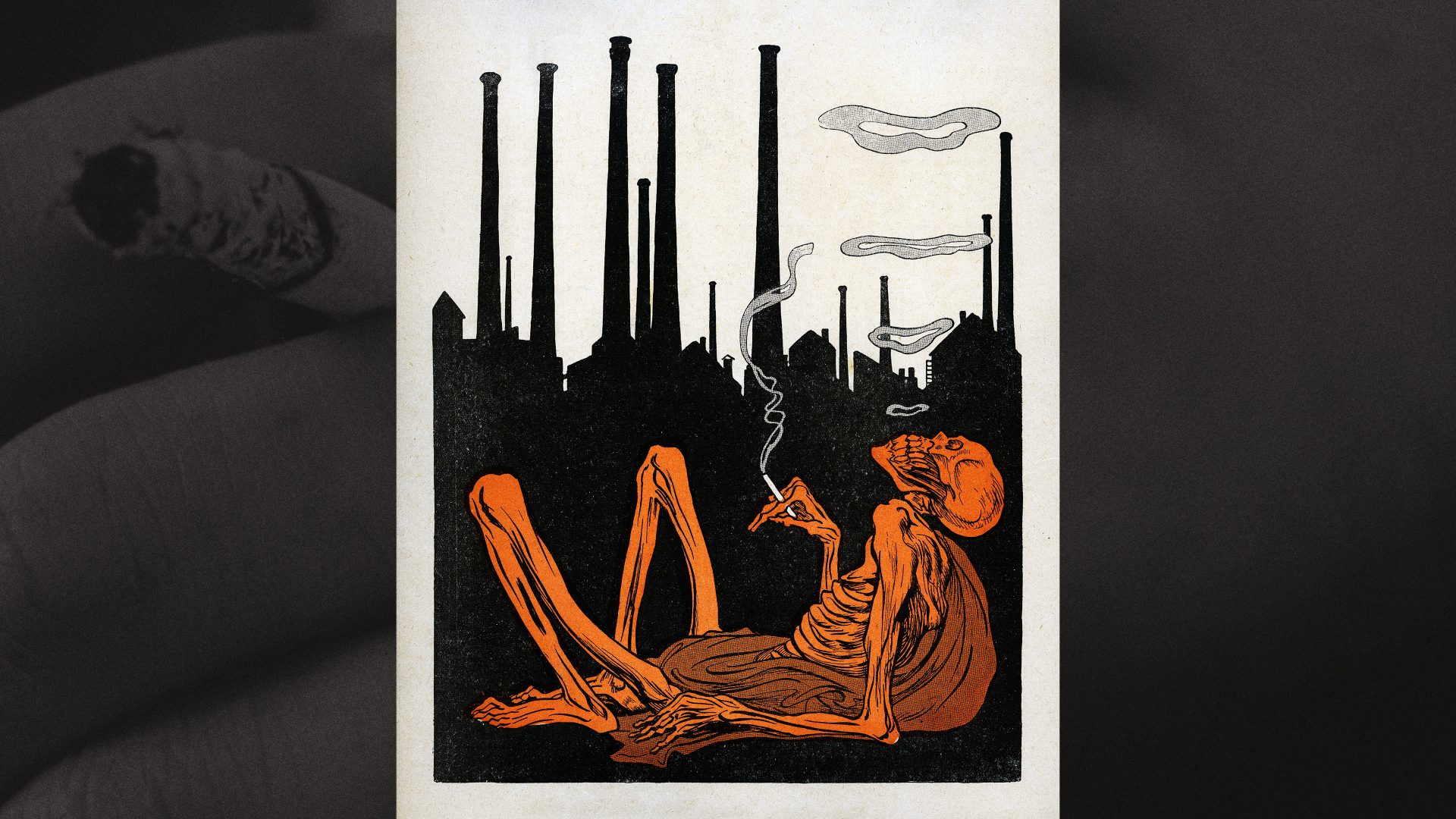

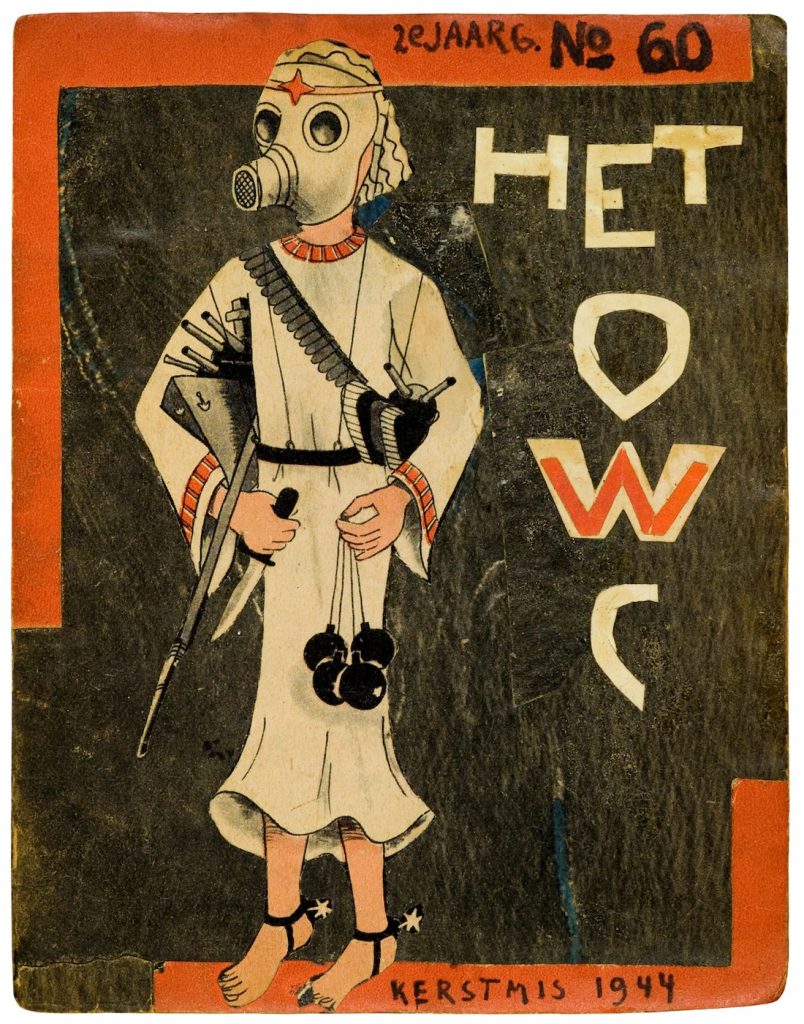

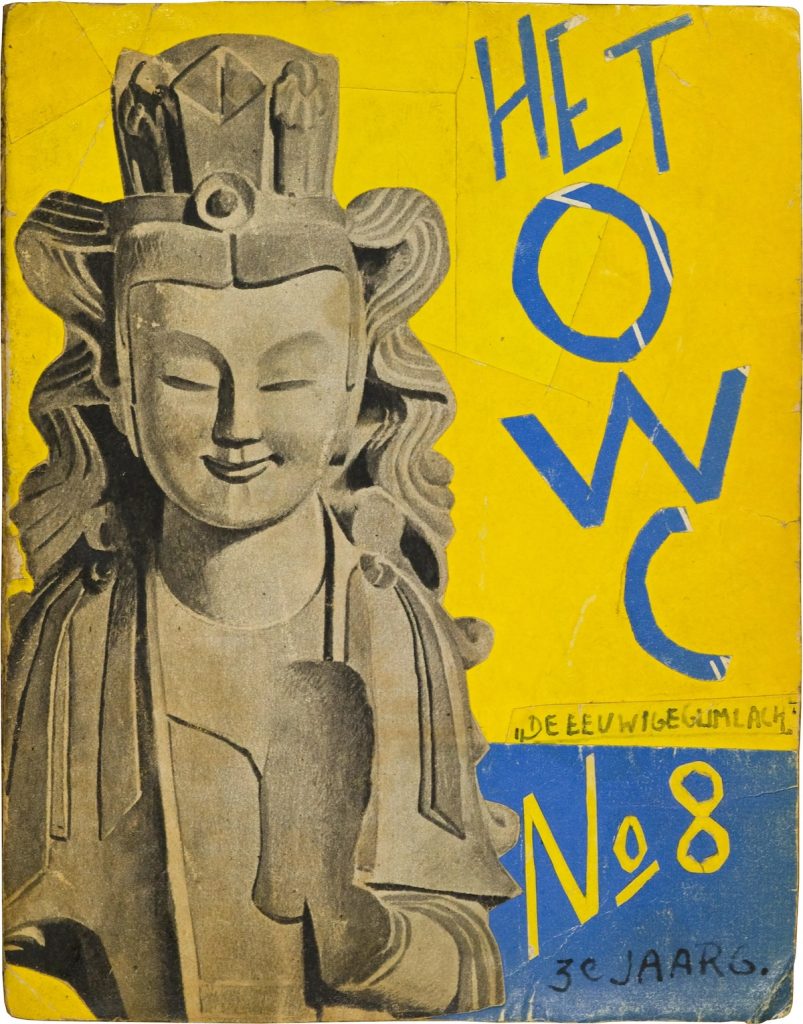

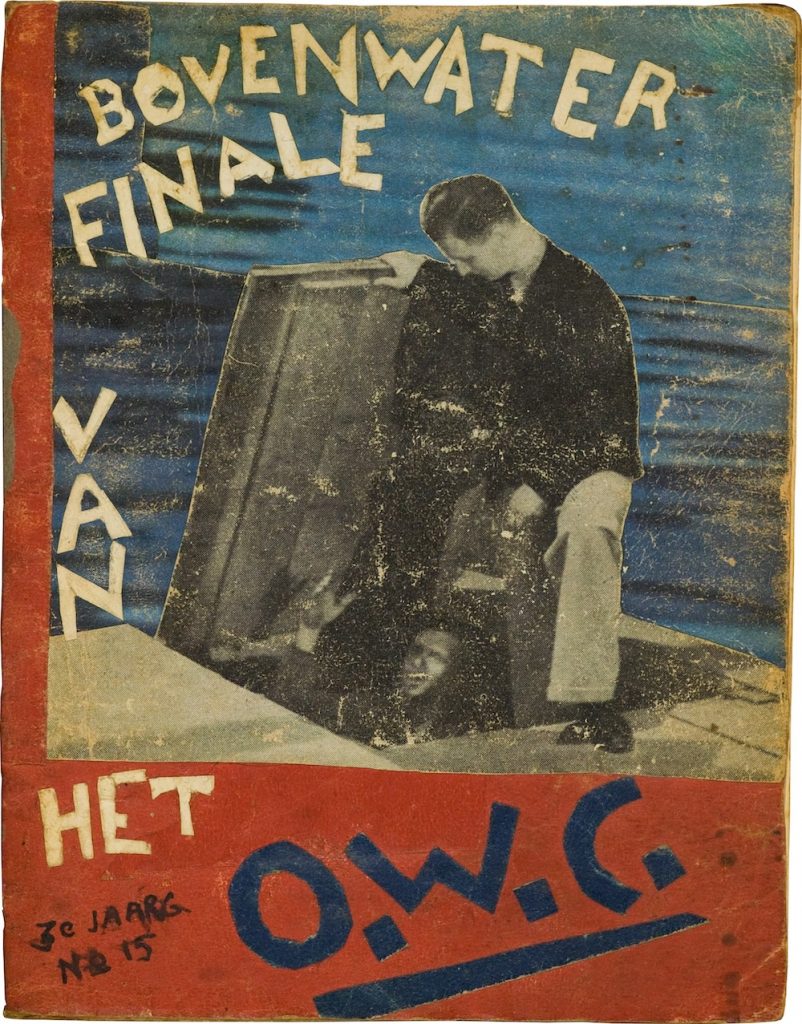

And then there are the magazine’s front covers, which Bloch created himself and a selection of which can be seen on these pages. Before the war Bloch was an importer of Persian carpets, and it was perhaps this that gave him a feel for pattern and form. He pieced the front covers together using the limited materials available, and the results are remarkable.

The collage style of cut-out photographs and hand-written headlines is strongly reminiscent of Dada, the art movement that emerged after the first world war, and the idea of an Underwater Cabaret has a pleasingly anarchic, Dadaist – almost Surrealist – feel to it. But even so, none of the artworks of the 1940s looked anything like Bloch’s magazines. To find a mixed media artist creating imagery of this sort, you would have to look to the 1960s and to artists such as Robert Rauschenberg.

In the final issue, in March 1945, the titles of the featured poems reflected the euphoria of the allied liberation of Holland: To the Allied Forces; Speak To Me About The War No More; and Freedom! In a poem titled Liberated! he wrote:

Always having to hang around

in the same place

And yet I didn’t keep my beak shut,

No, I sang my songs.

And later in the poem:

I can go out freely

And drink this liberty,

From now on I can let my song

reverberate in freedom.

But Bloch’s emergence into the light revealed a terrible picture of desolation. Europe was in ruins – and the reality of the Nazi persecution of the Jewish people was becoming horrifyingly clear. Bloch consequently discovered that both his mother and sister had been murdered in extermination camps. He was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust.

After the war, Bloch met and married Ruth Kahn, an Auschwitz survivor, and in 1948 they moved to New York. He took a full collection of his magazines with him to the United States, where he died in 1975, and the copies remained untouched in the family apartment for 75 years.

In 2021, his granddaughter, Simone Bloch, created an online archive, making the full collection available for the first time, and in 2023 a book was published in the Netherlands, The Underwater Cabaret: Kurt Bloch’s Satirical Resistance.

From February 9 to May 26, a collection of his work will be on display at the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

Bloch’s work is all the more striking for looking so modern – there is a vibrant, almost punk-like immediacy to his designs, and to their subversive, cutting humour. And it is hard to see them without thinking of people today who are also trapped in war zones, who are also hiding from the enemy and who, like Curt Bloch, are longing for freedom.