Occasionally a Private Eye cover really nails it. One such was in 2014. “Where to, Guv?” asks the cab driver. And the reply comes back from the Ukip supporter: “1957 – and step on it!”

That cover was so astute as it recognised that the idea of Brexit had precious little to do with Europe. Rather, it was fundamentally, and especially on the part of those older voters who made the decisive difference to the outcome, a grumble-cum-howl of protest, or even despair, about the modern world.

Did Private Eye get the chronology right? Were the 1960s, that most mythologised of all decades, when it all began to go wrong? I believe one can make a plausible case that that was when the long, slow-burning fuse was lit for half a century later.

We must start with de-industrialisation. Although the great step-change would come in the traumatic early 1980s, as Britain lost one-quarter of its manufacturing capacity in just two years, even in the 60s the direction of travel was unmistakable. At the start of the decade, employment was roughly equal between manufacturing and services, but by the end it had tipped decisively towards the latter, a change neatly symbolised by the moment the number of hairdressers passed the 100,000 mark.

Textiles, coalmining, shipbuilding, steel: all of Britain’s staple industries were in significant decline, as were the railways. This decline inevitably triggered the erosion of a working-class way of life, deeply in tune with industrial rhythms that had been established in the late 19th century and had come to seem permanent.

Take shipbuilding. It was hard not to be struck some years ago by the BBC TV documentary Billy Connolly: Made in Scotland, where The Big Yin reminisced evocatively and fondly about the unashamedly male-centric culture (in the words of one reviewer, “football, beer, swearing, hammering at colossal pieces of metal and being funny”) that he had imbibed as a young welder on the Clyde. Yet, implacably, it was a fast-dying industry in the 60s, and therefore a dying world.

No one has written more powerfully about the social and psychic impact of de-industrialisation than Jeremy Seabrook, who on the very day that Britain voted to leave published in the New Statesman a characteristically impassioned piece about the death of the industrial way of life. “The ravages of drugs and alcohol and self-harm in silent former pit villages and derelict factory towns,” he observed, “show convergence with other ruined cultures elsewhere in the world.”

Almost all of this still lay ahead at the end of the 60s, but the left-behind signs were starting to become clear. And given that in some distinct ways Brexit has been a very male – even alpha-male – phenomenon, it is relevant that the 60s themselves saw, more markedly than in either the 1950s or 1970s, a growing proportion of women in the British labour force, once such a masculine preserve. And soon, unimaginable not long before, they would even be entitled to equal pay.

As with de-industrialisation, so too with that pet hate of the Brexiteers, “globalisation”. Although it did not become a recognised phenomenon as such until the 1990s, and although exchange controls were still firmly in place, there were indications during the 60s of the way things were going. Not only was foreign ownership of British companies increasingly prevalent, epitomised by Nestlé taking over Crosse & Blackwell as early as 1960, but these years saw the rapid flourishing of international finance centred on the City of London. This led to the rise of what became known as the Euromarkets, which involved a dominant role for American banks and in effect represented stage 1 of the internationalisation of the City, to be followed two decades later by the much more publicised stage 2, the Thatcher-era deregulation known as “Big Bang”. The Square Mile was becoming ever more adrift from the UK economy.

As well as this, the remorseless corporate tendency in the 60s towards increasing size and concentration meant that the warning lights were on for old-style family capitalism, with its localism and often paternalism, and its two-way loyalty in the employer-employee relationship. Ownership of capital was increasingly divorced from managerial control; and, abetted by the arrival of American or American-style management consultants, we were inexorably on our way towards the bracing, shareholder-value, unsentimental, alienating world of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, now made flesh in the buildings of Canary Wharf.

In short, Harold Wilson’s 1960s rather than Margaret Thatcher’s 1980s was the decade when postwar capitalism began to go fatefully wrong.

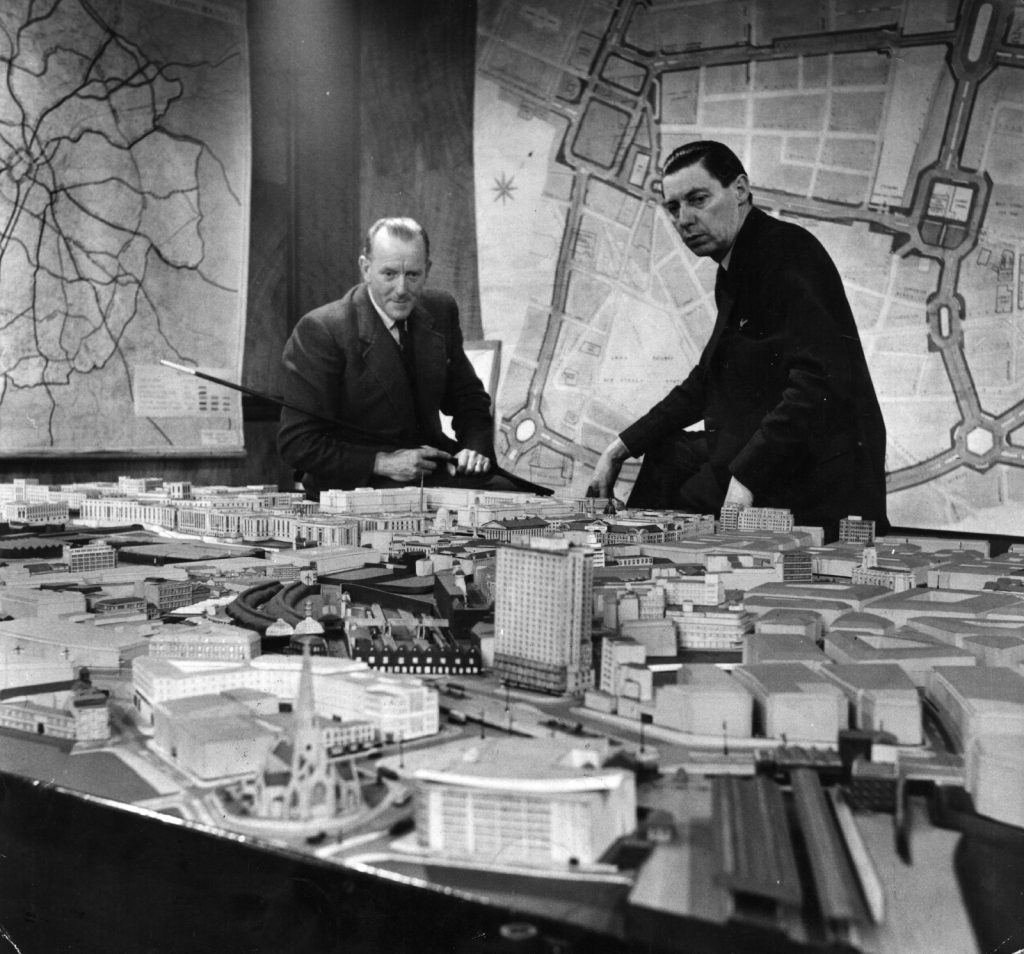

Fatefully wrong would also be how I’d describe what happened in the 60s to most of our city and town centres – a trail of wanton destruction, all too often to make way for uncompromisingly brutalist replacements. In Birmingham, car city, the architectural year-zero was caused by the construction of the inner ring road; in Blackburn it was the knocking-down of the entire central area for a huge shopping centre with accompanying car park; in Bradford, which JB Priestley in the late 50s had urged to get up to date, it was the demolition of Kirkgate Market to make way for an unlovely Arndale Centre. The mournful list goes on to include Newcastle, where under the leadership of the corrupt, charismatic, progress-loving visionary T Dan Smith the city was turned into what the architectural historian Gavin Stamp would sardonically call “the Croydon of the north”.

Much of all this, especially in urban conurbations outside the south of England, was understandable. Elderly Labour city and town councillors were strongly prejudiced against all things Victorian, an epoch they associated with Dickensian squalor. Opportunistic architects, developers and construction companies had little difficulty in pulling the wool over their eyes. The bipartisan mood at Westminster was strongly in favour of modernity and modernisation, often without examining too closely what that meant in practice, and public opinion was largely passive and fatalistic, albeit very seldom consulted.

An unblinking decade of top-down radical urban renewal left almost all our centres less human, less intimate, more brutalised, more homogeneous. And the legacy of this sudden loss of so many intricate and familiar local environments? I believe it has been a powerful one that still resonates, especially among older people, and its key components include a sharply reduced faith in progress, a widespread nostalgia for a lost world, and a desire to retrieve local identities from the commercial and consumerist monolith. A significant long-term cause, then, of the 2016 vote? To my mind, yes.

To all of which one has to add the related 60s story of what happened to working-class housing, in what was still, after all, a predominantly working-class society. For this was the decade of relentless slum clearance – up to a third of which could have been avoided with more imagination, more ingenuity and a different political climate. Instead of a humane, incremental, street-by-street approach, too much of the slum clearance was done in far too drastic and heavy-handed a way. This continued into the early 70s, when a TV documentary showed the great architectural critic Ian Nairn driving from Stockport to Manchester, and on both sides of the road it looked like Dresden the morning after. An emotional man, Nairn could barely contain his grief.

All of which meant the destruction of many, many working-class communities, with little conceivable possibility of reassembling them – not least given that much of the new housing was unsuitable and poorly built high-rise. This soon left many residents feeling trapped and quite quickly led to alienation, loneliness, serious drug problems (especially once heroin arrived big-time in the 80s) and higher levels of antisocial behaviour.

One can, I know, romanticise those old communities. But on the whole, they were a force for good, certainly a source of social and psychological stability, in comparison with the modern and infinitely more atomised world.

This was also the decade when Britain not only decolonised and explicitly retreated from great-power status, but also turned from an overwhelmingly monocultural society into something more diverse and multicultural. Undeniably, this was not a universally welcomed development, and a trio of landmark moments stand out.

First, the October 1964 general election, when – against the national trend of a swing to Labour – the largely white working-class Smethwick seat in the West Midlands saw a rare Tory gain, after a local and notorious campaign that had relentlessly played the race card. Then in April 1967, a major report by the think tank Political and Economic Planning (later published as a Penguin Special) revealed in conclusive detail the substantial degree of discrimination being practised in everyday life against non-white immigrants. A year later, on April 20 1968, Enoch Powell delivered his infamous “rivers of blood” speech, given at the same time that the Labour government was extending race relations legislation to cover housing and employment.

Amid other incendiary rhetoric, the shadow minister and Wolverhampton MP declared that the new law would be a further blow to ordinary English men and women who had “found themselves made strangers in their own country”. That was on a Saturday. Two days later he was sacked by Edward Heath from the shadow cabinet, and on the Tuesday 1,000 London dockers marched to Westminster with placards backing Powell. Meanwhile, Powell was receiving a flood of letters – over 100,000 of them by the end of May, most of them supportive. And soon three words would be born, to be heard in pubs and working-men’s clubs over the next 10, 20 or more years – the words “Enoch was right”.

Not, I must emphasise, that it was just a significant chunk of the indigenous white working class whose prejudices were legitimised by Powell; it was also large numbers of white middle-class people – “the carnivores” as opposed to “the herbivores”, to use Michael Frayn’s immortal coinage about the contrasting middle-class types.

One of those carnivores was my father, a retired army officer, when in about 1977 he had a letter in his local paper, the Shrewsbury Chronicle, in effect saying three other words: “Send them back”.

Tellingly, when it came to Powell’s massive postbag in the spring of 1968, very many of the supportive letter-writers went out of their way to insist they were not “racialist” and did not believe in the biological inferiority of non-white races. Instead, to quote Clair Wills from her superb Lovers and Strangers, “they feared for British culture and traditions which could not survive under the pressure of so many newcomers, who brought with them alien ways of behaving.

A surprisingly small proportion of letter-writers focused on the economic consequences of immigration – the strain on social services, or the burden on taxpayers, for example. The overwhelming emphasis was on cultural rather than economic losses.”

So, once again then, there arises the crucial concept of loss – and loss is a powerful emotion that one should in general be willing to empathise with, if not necessarily to endorse. After all, I suspect that in 2019 there were many New European readers who felt, as I did, that following that summer’s hard-right Tory coup, they were somehow no longer living in their own country, that almost by the day Britain was becoming a different place. Inevitably, one’s emotions were of loss, of bewilderment, of impotent anger. To understand is not to condone; but it is to understand.

But what about peace and love and all that? What about Beyond the Fringe, the Pill, That Was the Week that Was, the Profumo scandal, the end of deference, the conclusive end (or so it seemed at the time) of Etonian prime ministers, the abolition of capital punishment, the decriminalisation of homosexuality, the legalisation of abortion, less restrictive divorce legislation, an ever more visible and radical-minded youth culture – what about all these emblematic 60s phenomena?

Naturally enough, they will always have pride of place in any progressive, liberal-minded account of the 60s, as life loosened up after the constraints of the 50s. Yet the inconvenient historical truth was that at that time, or indeed looking back, many millions of people would have wished it otherwise. Social conservatism remained deeply entrenched.

When it comes to shifting social trends, the diaries of obscure, “unknown” people are often the most revealing. Take Gladys Langford. A retired teacher, she was living a solitary and rather miserable life in Islington, but still determinedly keeping her diary.

“These young thugs smashing seaside resorts on Bank Holidays are the curse of the Welfare State, so rich in money allowing them so much for clothes, cars, scooters and travelling,” she reflected on Whit Monday 1964. And she added: “A big percentage are Irish. They need birchings or fire hoses turned on them & their transistors.” Or on a hospital visit in January 1967: “Foot agonising. Saddened to learn attractive younger chiropodist uses the ‘four-letter word’. I dislike the mascara around her eyes.”

Inevitably, the box in the corner was a main focus of complaint about the way things were going.

“It joked about religion and sacred things” and “It was often coarse” were the two main reasons why in 1963 so many viewers objected to That Was the Week that Was – and when Jonathan Miller took over the arts programme Monitor, a representative comment was that he was “too clever by half”.

In a category all of her own, as a critic of the seeming zeitgeist, was Mary Whitehouse. She made an almost instant national impact when, in January 1964, she launched the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, aimed at reducing sex and violence on TV.

Soon afterward, Miss FM Arthur of West Kirby in the Wirral congratulated Whitehouse on her initiative and gave a list of “What I would like to see on Television”. Her suggestions included “more travel films, especially with Johnny Morris in them” and “more films about animals”, while “programmes of which I never tire are Dr Finlay’s Casebook, This Is Your Life (with Eamonn Andrews of course), Dixon of Dock Green, Mr Worth, Eric Sykes & Hattie”. By contrast: “I dislike most of the Television plays, which are morbid, immoral and disgusting… I hate Beatles & screaming teenagers & put them off as soon as I can reach the TV knob…”

In short, taking these examples as a whole, we are talking about culture wars; and this was the decade when the battle-lines were drawn, often a long way from swinging London.

To end with the story a friend once told me… It was 1969, a Sunday evening in Goole (a town about 30 miles inland from Hull), and he had taken his girlfriend to the pub – where the barman refused to serve them. Their crime? She was wearing trousers. Carnaby Street and the King’s Road may have been at their fashionable height, the Rolling Stones may have been playing at Hyde Park, but Goole was still Goole.

Over the ensuing half-century, the forces of social conservatism would enjoy two defining moments in the sun. The first came in 1979, as Margaret Thatcher was swept to power not, in my opinion, because of her free-market views, but instead because many believed (on the whole mistakenly, as it turned out) that she was the person to turn the clock back to a Britain, above all an England, as it had been before the 60s; and of course the second came in June 2016, when incidentally the Leave vote was higher in Goole than almost anywhere else. “Nostalgia for the past” was the instinct to which the EU’s Michel Barnier would attribute the Leave vote. To a large extent he was right.

David Kynaston’s A Northern Wind: Britain, 1962-65, the latest of his Tales of a New Jerusalem series, is published by Bloomsbury in September