Any journalist who has been doing the job for long enough has one story that they’re known for, either by those in the industry, or – if they’ve risen to prominence for one reason or another – by swathes of the country at large.

They also have absolutely no say over which story it is, or why – it’s just whichever one broke through enough to lodge indelibly in the mind of their colleagues, and from that moment on, you’re “the reporter that did x”.

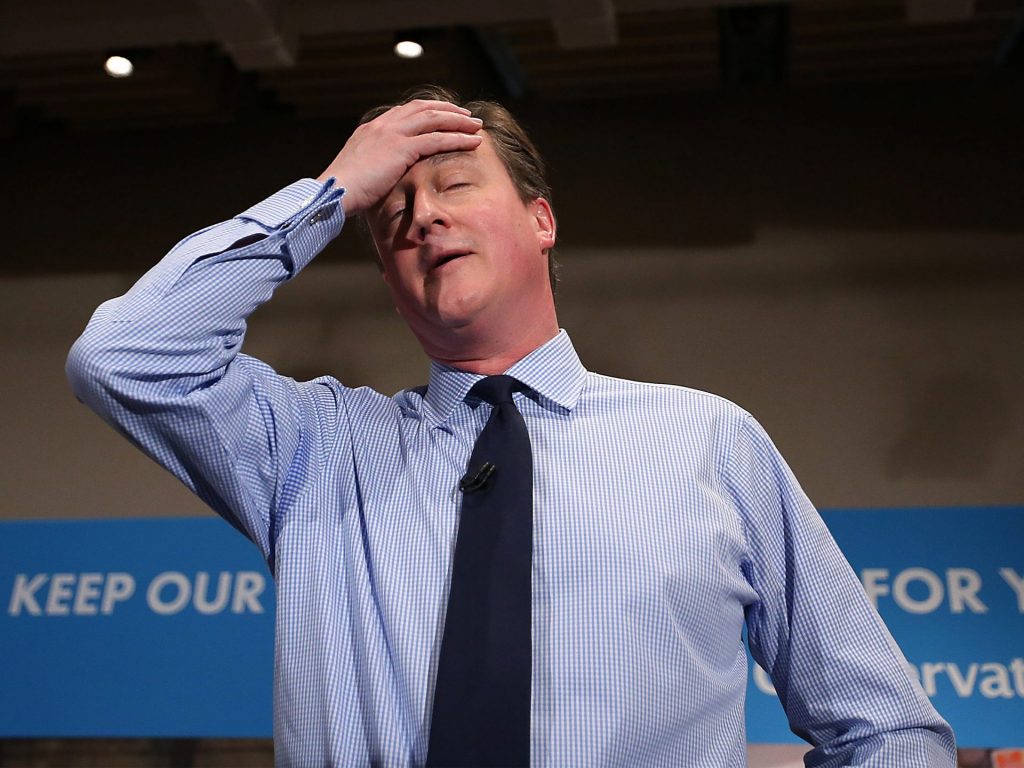

So it is, that whatever else she has achieved or will go on to achieve in her life, Isabel Oakeshott will always be the journalist who wrote a front page article accusing David Cameron, then the prime minister, of performing a sex act on the corpse of a pig.

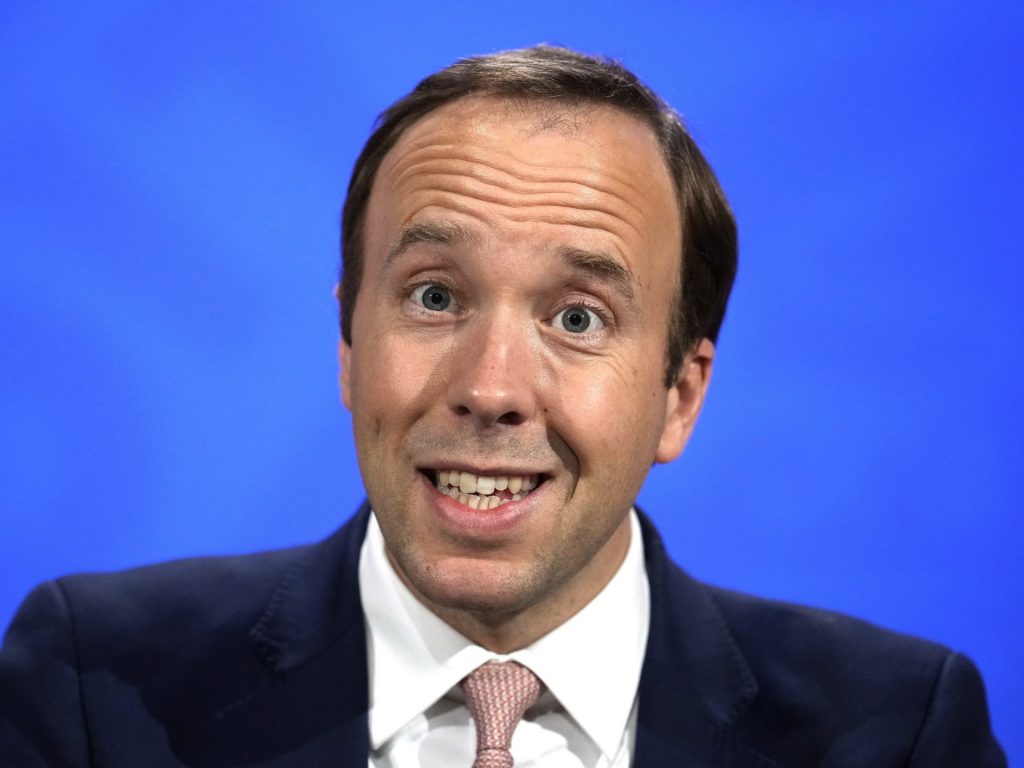

That is not, though, to deny Oakeshott her due for the extraordinary political impact of her journalism – which has led to the resignation of a UK ambassador to the US, to the jailing of a former government minister (along with Oakeshott’s own source) and to the (further) humiliation of everyone’s favourite political punchbag, Matt Hancock.

But Oakeshott is a bigger figure than just her own work would suggest, as she is also half of one of the right wing’s most prominent power couples. Since 2018, she has been in a relationship with Richard Tice, a multimillionaire businessman from the property sector.

Tice had been a prominent Conservative donor, but his frustrations with the party over Europe led him to co-found first the Leave.EU campaign and then the Brexit Party in turn, with Arron Banks and Nigel Farage respectively. After the referendum, in part over their frustrations over the handling of Covid-19 and their chafing at lockdown restrictions, Farage and Tice broadened the Brexit Party’s remit, renaming the party Reform UK. Tice now serves as its leader.

Away from politics, Tice has done pretty well. He was CEO of CLS Holdings from 2010-2014, and played a role in the development of ultra-prime UK property, including Vauxhall Square and The Shard.

This business success, coupled with the eventual “success” of securing Brexit – of which he was a very early supporter and financial backer – helped convince Tice he should play a bigger role in politics, rather than sit back as a funder. Associates suggest he has a very high degree of confidence in his abilities as a politician and a campaigner, and thinks his views should hold commensurate weight. He is also reputed to take criticism to heart, and to hold grudges.

Reform may not perform well in polls or at the ballot box, but it wields a disproportionate influence on the right of British politics to pose a threat of the Conservative party. Tice’s political goals and Oakeshott’s journalistic targets are extraordinarily intertwined. While Oakeshott’s first marriage, to journalist Nigel Rosser, was largely in the background, no one can make that same accusation about Brexit’s alpha couple.

Given her alignment with the firmly anti-establishment “bad boys of Brexit” crowd (a term popularised by her own book of 2017), Oakeshott herself is something of a consummate establishment figure. Privately educated in the prominent Scottish schools of St George’s and Gordonstoun – where King Charles III famously unhappily boarded – she has enjoyed nearly two decades as a lobby journalist for the Sunday Times and a political editor-at-large for the Daily Mail.

Oakeshott has been waspishly described by those who know her as charming and extremely easy to like, but far more difficult to stay liking – not least in part thanks to her extraordinary willingness to sacrifice friendships or other bonds of trust in the service of a story she wants to tell. Such is Oakeshott’s record of betraying sources, friends, or even ghostwriting clients that an often-asked question in Westminster is how she ever gets anyone to trust her in the first place.

One lobby insider noted that this, in a way, made Oakeshott the perfect journalist for the Johnson era of politics – a PM who would do almost anything to advance his own causes (in his case, himself), mirrored by a journalist who would do the same.

But where critics see a willingness to betray those around her, advocates note that she can’t be accused of putting cosy “bubble” relationships ahead of the public’s right to know. Either or both camps could be correct – but it is certainly a tangled web that Oakeshott weaves.

The story that propelled Oakeshott to industry notoriety, where before she had been a relatively well-regarded figure, was her revelation that a then-serving cabinet minister, Liberal Democrat Chris Huhne, had persuaded his wife, economist Vicky Pryce, to pretend she had been driving when he picked up a speeding ticket several years previously.

Pryce was, at the time, in the midst of a very acrimonious divorce from Huhne, and had been looking either for vengeance or to get a sense of his “true” character out to the public. Oakeshott helped provide Pryce with recording equipment to entrap Huhne in a confession of the cover-up, but when this failed, Pryce also approached another journalist with a version of the story in which someone else rather than her took the points for him.

The farrago not only ended Huhne’s ministerial and political career, but led to jail time for both Huhne and Pryce – with Oakeshott testifying in the court case that led to the imprisonment of her source, breaking one journalism’s few strict taboos: you never reveal the identity of someone who spoke to you off the record.

Oakeshott’s unapologetic public stance about the case was all the more extraordinary because of her personal ensnarement with Huhne and Pryce, with whom she shared at least some degree of friendship, not least via her cousin Matthew Oakeshott, a Liberal Democrat peer and friend of the former couple. If anyone concerned had thought themselves protected by being part of her circle, they were proven very wrong indeed.

The startling tale about David Cameron involved less public betrayal, but caused perhaps nearly as much public drama and came to highlight Oakeshott’s later modus operandi of causing a ruck with splashy political books.

Oakeshott’s Cameron biopic was the start of a successful alliance with the multimillionaire Conservative donor (and former peer) Michael Ashcroft, who owns, among other businesses, the political publisher Biteback. The otherwise conventional biography included what turned out to be a second-hand tale from David Cameron’s days at Oxford University: That at an initiation for the decadent Piers Gaveston society (known for holding the university’s best parties), Cameron had inserted his penis into the mouth of a pig’s head.

The uncorroborated piece of gossip would normally never make it anywhere near publication in a mainstream newspaper outlet, but thanks to its publication in a book, the Mail splashed with the story, and – in part thanks to its uncanny resemblance to a Black Mirror plotline – it went enormously viral. Rumours circulated for months that Ashcroft had offered to indemnify the Mail against any possible libel claims over the story, but these were never corroborated.

Photos: Peter Macdiarmid; Matt Dunham/WPA Pool/Getty

Oakeshott’s success at causing a political splash was established by her Cameron book and its successor, The Bad Boys of Brexit – which profiled Nigel Farage, Arron Banks, Andy Wigmore and her soon-to-be partner Tice as the real architects of Brexit. A much-touted Hollywood film of the book has failed to appear, sadly depriving us – as the Telegraph promised in 2017 – of the sight of Farage being played by “Oscar-winner Kevin Spacey”.

Interestingly here, Tice somewhat corresponds with his partner, in that while some feverish Remainers imagine that the “Bad Boys” still regularly meet and plot together, the reality is that they often fall out in lumps, with some barely on speaking terms with the others. That is, after all, a lot of egos for a small political space.

It is perhaps Hancock’s eternal need for both attention and validation that blinded him to the risks of choosing Oakeshott as his ghostwriter for his largely derided (and hagiographic) autobiography. Her relationship with Tice was a matter of public record, and both were serious critics of the government’s approach to lockdown (though neither has engaged in the full Covid conspiratorialism of many who share their politics).

Yet Hancock clearly thought he had some form of legal or contractual protection, and so shared tens of thousands of WhatsApp messages to help Oakeshott write and give colour to the book – which several months later she turned over to the Telegraph, publishing story after underwhelming story based on an absolutely extraordinary breach of trust.

Hancock was hardly a likely candidate for a political comeback even before the leaks, but they did help to cement his position as a Westminster laughing stock, even without his stay in the jungle.

The recent fractious infighting of the Conservative Party leaves Oakeshott and Tice at a fascinating political juncture. Farage was largely stirring the pot when he suggested Boris Johnson and a coterie of Conservatives could find a new home in Tice’s Reform UK party, but, depending on the course of the next election, it could actually become a political force.

If the Conservatives lose the next election, a civil war inside the party is a virtual inevitability. A victory of the right wing culture war faction would move Tice’s views and his party towards the mainstream – perhaps opening the door to his becoming an MP or a peer for the new Conservatives.

A victory of more moderate or “wet” Tories could benefit the couple in other ways, as it would inevitably provoke a splinter from the culture warriors. In those circumstances, Farage’s slightly cheeky offer (designed to grab a headline or two) could become a serious one.

The near future looks like a win-win for Tice and Oakeshott – she now earns £250,000 a year at TalkTV – and their agenda. Insiders at the channel were said to be understandably annoyed to see her publishing scoops at the rival Telegraph, and she and Tice were a disappointment when they jointly filled in for Piers Morgan. During one February show, the 90-year-old Lord Heseltine ran rings around them.

Oakeshott never needed to do any of this – she had a comfortable existence and a good establishment reputation. Tice could similarly have remained a wealthy political donor, far away from the political cut-and-thrust. Them being where they are – and the decisions they’ve made to get there – are no accident. They have chosen this.

Many who have encountered them on the way, though, may be ruing the choices they made with regard to the couple. But experience suggests that even now, someone else might be getting the charm treatment – how might that work out for them?