Britain left the EU’s single market and customs union, and ended freedom of movement, in the middle of the Covid pandemic. Now that the pandemic restrictions have been lifted and the country has gradually reopened, it’s becoming evident that the UK economy has suffered considerable damage.

Predictably, the UK government likes to claim that the damage is entirely caused by Covid and is nothing whatsoever to do with Brexit. It points to factors affecting all countries, such as disruption to shipping and global energy price rises.

Equally predictably, prominent Remainers are claiming the reverse. The truth, as ever, is no doubt somewhere in between. But whether due to Covid or Brexit, or some combination of the two, Britain is facing a stagflationary winter. The question is how long it will last.

It was always likely that there would be some inflation as the economy reopened after the pandemic. Covid control measures severely restricted consumer demand, but more importantly, damaged the supply side.

International supply chains were severely disrupted by Covid-related measures imposed by countries all over the world. And large parts of the UK’s important service sector were shut down completely for months on end: many businesses did not survive. Hospitality, particularly, is considerably diminished.

But there are additional sources of inflation. The first is sharply rising energy prices. Demand for energy crashed in the beautiful spring and summer of 2020, as transport evaporated, offices and shops closed, and people sought solace in outdoor activities. Petrol prices fell below £1 a litre for the first time in 20 years.

In response to falling demand, oil producers cut production. But now, as economies reopen and demand for energy returns, energy prices are rebounding from last year’s lows. In fact, because it takes time to ramp up production again, they have overshot.

The overshooting is amplified by disruption to supply chains and speculative activity on commodity markets. For how long energy prices will continue to rise depends on how long it will take the supply side to adjust to increased demand, and the extent to which demand will be dampened by rising prices.

High energy prices will force many businesses to raise prices for customers, cut back production, or lay off staff. Some could go out of business.

Households may have to cut back discretionary spending, especially those at the lower end of the income distribution who are also facing benefit cuts and tax rises that will squeeze their incomes considerably.

The government’s plans to impose a green levy on gas bills in pursuit of its climate change targets will make matters worse. In the coming winter, some may be forced to choose between heating and eating.

A second source of inflation is labour shortages. Unemployment is somewhat elevated and likely to rise as the furlough scheme ends.

In conventional economic models, high and rising unemployment dampens inflation. But there are no conventional economic models that combine unemployment with labour shortages in what were previously considered (wrongly) to be low-skilled sectors, such as seasonal fruit picking, animal slaughter, and HGV driving.

Employers are responding to these shortages by raising wages, in some cases considerably. The additional costs will inevitably be passed on to consumers in some form. Whether these labour shortages arise from domestic issues such as the IR35 tax change that came into force in April 2021, or from ending freedom of movement for EU workers, or some combination of both, is at present unclear.

But whatever the cause, policymakers in post-pandemic, post-Brexit Britain are rapidly re-evaluating their view of labour markets and the way they affect inflation. The Phillips Curve – which suggests an inverse relationship between unemployment rates and wages rises – though perhaps not dead, is certainly undergoing major surgery.

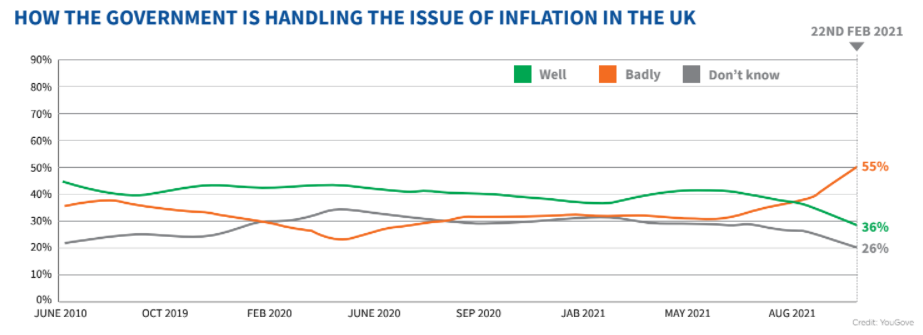

A third cause of inflation is shortages of goods because of supply chain disruption. Some food prices, for example, have been rising. Again, this could prove short-lived if demand adjusts downwards and/or businesses adjust their supply chains.

But shortages of labour and goods could prove lasting if they are primarily caused not by the pandemic but by barriers to trade and restricted movement of people. And even if they are not, government policies deliberately aimed at raising wages for large numbers of lower-paid people without increasing productivity could cause accelerating inflation without much in the way of economic growth.

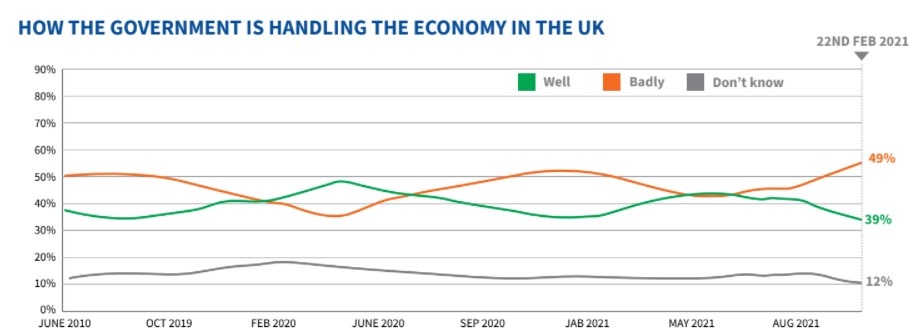

Inflation without growth is known as ‘stagflation’. It was last seen in Britain in the 1970s, though its ghost briefly appeared in 2011-12 when growth slumped and inflation touched 5%.

The very high interest rates of the 1980s eventually tamed the inflation of the 1970s, but at the price of what was then the deepest recession since the Second World War.

Unemployment, particularly among young people, rose to the highest levels since the 1930s. It took a decade to bring it down again – a decade which saw the destruction of much of the UK’s heavy industrial manufacturing base, especially in the north and the Midlands.

The government’s levelling-up agenda seeks to reverse the decline suffered by these regions since the 1980s. In his speech to the Conservative Party conference, Boris Johnson outlined an intention to develop a high-skill, high-wage economy.

The principal strategy for achieving this appeared to be restriction of immigration. But upgrading the domestic workforce’s skills to plug the labour market gaps will take time. And although many would welcome higher wages, if wage rises feed through into price rises, no-one will be any better off. If there is to be a post-Brexit dividend, it must take the form of higher productivity. Sadly, the history of the last few decades suggests that this will not be easy to achieve.

This creates a policy dilemma for the Bank of England. Should it raise interest rates to bear down on inflation by dampening demand, or should it ignore near-term inflation and concentrate instead on measures to increase economic growth?

The mood music from a growing number of Bank officials is that inflation could prove stubborn, and that the Bank might therefore raise interest rates sooner than previously thought.

But I look back to 2010, and recall how energy price increases, tax rises and benefit cuts knocked the stuffing out of an economy only just emerging from the post-financial crisis recession.

It was years before growth returned. The pandemic recession has been much deeper, and whether caused by Covid or Brexit, the supply side damage is much more extensive.

The government is already tightening fiscal policy, even though robust growth has not returned and wage growth is really only returning to the pre-pandemic trend. And the barriers to trade created by Brexit are raising costs for businesses and making it harder for them to compete internationally.

I fear that the post-Brexit stagflationary winter could prove long, hard and very cold.