You wait ages for a Tobias Smollett anniversary then two come along at once. March this year brought us the 300th anniversary of his birth, next week marks 250 years since his death in Italy on September 17, 1771. March passed with the landmark almost entirely unremarked upon; this month looks likely to be equally low key.

Which is a shame, as Smollett was with Laurence Sterne, Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson a pioneer of the novel as we know it today, an architect of modern literary criticism, a pretty decent poet, a meticulous chronicler of history and a man whose sheer force of character – irascible, opinionated and immensely fond of a feud – still simmers from the pages of his work today.

He was always cross about something, but he was funny with it. Robert Burns admired Smollett’s “incomparable humour”, William Makepeace Thackeray called his final novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker “the most laughable story that has ever been written since the goodly art of novel-writing began”, while in George Eliot’s Middlemarch, Brooke instructs Casaubon to “get Dorothea to read you light things, Smollett – Roderick Random, Humphry Clinker. They are a little broad, but she may read anything now she’s married, you know. I remember they made me laugh uncommonly – there’s a droll bit about a postilion’s breeches.”

One could even argue that without Smollett there would be no Charles Dickens, as among the small selection of books owned by Dickens’ father was a selection of Smollett which the future novelist read and re-read until he could virtually recite them. The Pickwick Papers in particular, with its cast of larger than-life characters making their way around the country, is pure Smollett.

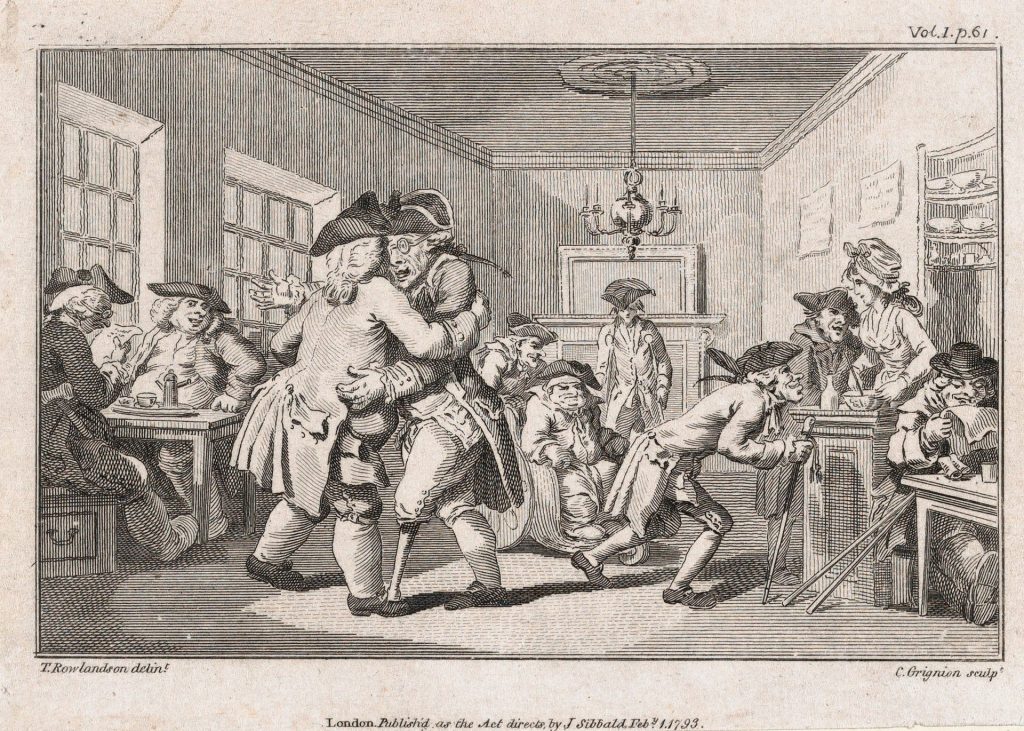

He was also achingly funny. Sir Walter Scott wrote that, “Smollett excels in broad and ludicrous humour. His fancy seems to run riot in accumulating ridiculous circumstances one upon another, to the utter destruction of all power of gravity; and perhaps no books ever written have excited such peals of inextinguishable laughter as those of Smollett.”

In the light of these endorsements ringing like a peal of cathedral bells, it’s hard to understand why the bracketing of Smollett’s birth and death anniversaries within 2021 are not being more widely marked. He has been out of the limelight for a while, it’s true. His fiction is not exactly subtle, packed as it is with vehement satire on the mores, hypocrisy and injustices of 18th century England as well as a level of scatological humour that sometimes feels as if every bodily function of every character is the launchpad for a gag.

You won’t find much in the way of depth and nuance in his characters either, but the satire still bites, the plots rattle along and the jokes are still hilarious more than 250 years after they were written.

Smollett’s output was phenomenal too. He translated Cervantes’ Don Quixote into English and edited The Critical Review, one of the first literary publications dedicated to books. He wrote a four-volume Complete History of England, put together the enticingly-named Compendium of Authentic and Entertaining Voyages, edited a midwifery textbook, ghost-wrote a diplomat’s travel memoir, edited and contributed entries to the ambitious Universal History from the Earliest Account of Time to the Present, translated a journal of French economics, contributed translations to and edited the complete works of Voltaire in 34 volumes and produced the eight-volume The Present State of All Nations.

No wonder fellow satirist John Shebbeare, one of many writers with whom Smollett found time to conduct a lengthy feud, said he “undertakes to fit up books by the yard on all subjects”.

Born in Dalquhurn, just north of Dumbarton in 1721 to the laird of Bonhill, a landowner and judge, Smollett studied medicine at Glasgow University but had literary ambitions from an early age. He travelled down to London in 1739 with the script of a play he’d written, The Regicide, under his arm hoping to see it performed but was unsuccessful. Instead, he took a naval posting as ship’s surgeon on HMS Chichester and sailed for Jamaica.

He witnessed first-hand the carnage of the disastrous Battle of Cartagena, scenes that never left him, and in Jamaica met and married Anne Lascelles, the daughter of a plantation owner who kept a large number of slaves.

By 1744 Smollett was back in London to establish a medical practice, first in Downing Street, then Chelsea, but he still harboured ambitions to make a living from his pen. The publication in 1748 of The Adventures of Roderick Random, based on his naval experiences, made his name. Witheringly critical of the hypocrisy of contemporary society and the leadership of the Royal Navy, it was a daring work that gave an unflinching account of conditions on board ship. It had an impact, too.

Sixty years later Leigh Hunt was writing to Percy Bysshe Shelley of how Smollett “is understood to have done immense good to the poor wounded sailors in naval fights by those pictures of pitiless surgery and amputation in Roderick Random”.

It was The Expedition of Humphry Clinker that would be his most enduring legacy, however. Published a few months before Smollett’s death in 1771 it was written with its author exhausted from a lifetime of relentless toil and travel and in declining health with asthma and tuberculosis, yet is probably his least misanthropic work.

It’s an epistolary novel following a Welsh squire named Matthew Bramble and his entourage on a recreational tour taking in Gloucester, Bath, London, Harrogate, Durham, Edinburgh and Glasgow, presented as a collection of letters from different characters. There is plenty of Smollett himself in Bramble, and the novel betrays a valedictory air.

Bramble mellows tangibly as the book progresses and there are recognisable tributes to friends of Smollett’s alongside emphatic skewerings of enemies. Humphry Clinker is his masterpiece, and one hopes that Smollett, dying in Italy when the novel was published in London in June 1771, managed to hold a copy in his hands.

“It galls me to the soul when I think how much that poor dear man suffered when he wrote that novel,” said his widow after Smollett’s death. Anne had also had to bury their only child, Elizabeth, in 1763. The death of the 15-year-old devastated both her parents and possibly hastened Smollett’s decline.

His final years were spent mostly abroad. Elizabeth’s death, Smollett’s respiratory issues and his campaigning political journalism on behalf of fellow Scot the Earl of Bute making him a target in a wave of anti-Scottish feeling in England made it prudent for the couple to head south to warmer, less hostile climes.

“Genius is lost,” he complained of England in a parting shot, “learning undervalued and taste altogether extinguished.”

His subsequent exile was turned into a feisty travelogue, Travels in France and Italy, which satirised the Grand Tour and catalogued the reality of life on the road in 18th century Europe. His experience of Brits abroad sounds uncomfortably familiar, all “raw boys, whom Britain seems to have poured forth on purpose to bring her national character into contempt: ignorant, petulant, rash and profligate”, and the book’s unflinching critiques of Europe’s inns and cuisine led Laurence Sterne to lampoon him as the miseryguts Smelfungus in A Sentimental Journey, a book effectively written in response to Smollett’s.

Many have sought to condemn Travels in France and Italy as xenophobic but it was British attitudes he was aiming at, not the countries he passed through. Indeed, he praised Nice so much there’s now a Rue Smollett running through the city.

In his travel writing as well as his fiction and journalism Smollett was way ahead of his time. Two hundred and fifty years on from his death by the sea in Livorno – his last words to his wife “all is well, my dear” – we can only wonder what he would have made of the 21st century. A Humphry Clinkeresque wander through Brexit Britain would be quite something, as would a Smollettian update of his Complete History of England.

“I am old enough to have seen and observed that we are all the playthings of fortune,” he wrote in a letter to the actor David Garrick, “and that it depends upon something as insignificant and precarious as the tossing up of a halfpenny whether a man rises to affluence and honours, or continues to his dying day struggling with the difficulties and disgraces of life.”

As a last line to a volume of the Complete History bringing the story of England up to the present day, that would more than suffice.

A European Library

A weekly selection of fiction and non-fiction, new and old, to build a comprehensive literary portrait of our continent.

6. THE PRISONER OF ZENDA by Anthony Hope (Oxford World Classics, £7.99).

The ultimate in swashbuckling adventure, Hope’s 1894 account of English gentleman Rudolf Rassendyll being persuaded to stand in for the incapacitated Prince Rudolf of Ruritania, whom he resembles to an uncanny degree, at his coronation in order to thwart a coup attempt was a bestseller on publication and has produced countless imitations since. The fictional small, German-speaking Kingdom of Ruritania was conjured so vividly it formed many British people’s idea of ‘Europe’ for generations, and was so convincingly drawn travellers even went looking for it (Ruritania is described as being a short train ride from Dresden). A hugely enjoyable rip-roaring adventure of chivalry and romance.