Imagine the following: in response to last week’s disclosure that July 2023 was set to be the hottest month on record, and to the warning by United Nations secretary-general António Guterres that “the era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived”, it is agreed at an emergency meeting of the UN security council that the time for incrementalism and half measures is over.

In a single, sequestered location – a complex of buildings somewhere in Europe – 2,000 of the world’s most brilliant climate scientists, engineers, green tech entrepreneurs, data analysts and public policymakers are convened with a single, unambiguous objective. By August 2025, they must produce a planetary manual of detailed reforms to ensure that the 2015 Paris Agreement is honoured; to halve carbon emissions by 2030; and to reach net zero by 2050.

Crucially, their 18-volume “Green Book” becomes the single item at the COP summit that follows its publication. The work of the 2,000 must be turned into a binding international treaty for immediate implementation, bristling with meaningful sanctions to be imposed upon non-compliant nations.

Hard to envisage, isn’t it?

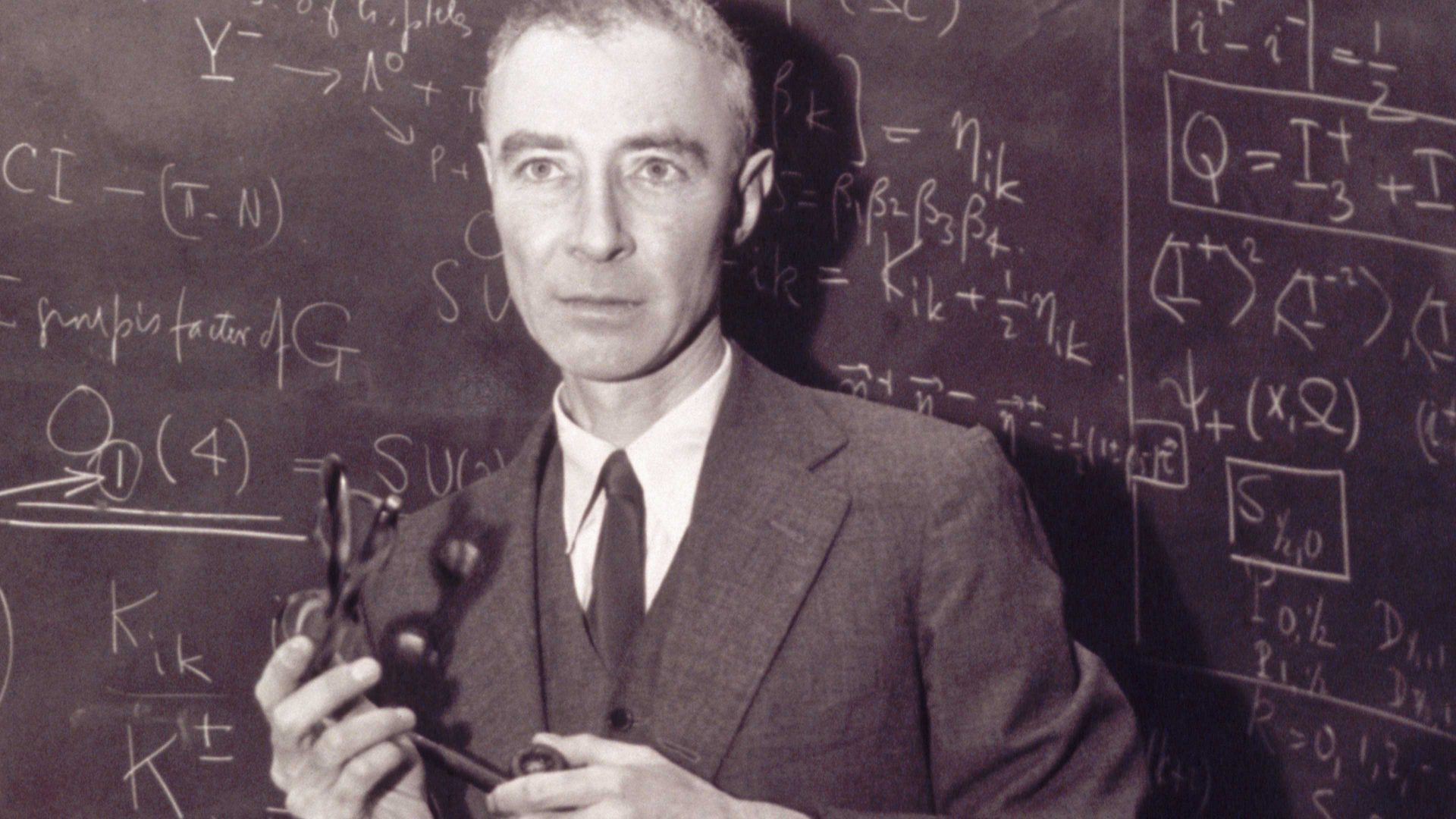

I have now seen Oppenheimer three times, and I’m going again today (I know, I know). More than any movie I can recall, Christopher Nolan’s epic cinematic saga rewards repeat viewings. The central dilemma faced by J Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the director of the Manhattan Project, is mythic in scale: how did a quantum physicist justify the creation of an atomic weapon so powerful that it killed 70,000 in a single blast? Was the success of his team a triumph of the intellect, or a betrayal of all that science stands for?

In this respect, the movie shreds the nerves and troubles the conscience to brilliant effect. But it also poses an unavoidable question: could anything resembling a Manhattan Project be organised today? Could the greatest minds and practical geniuses of our age be recruited to a single, integrated team to collaborate and tackle one of the many emergencies facing humanity: the towering challenges of artificial intelligence; of pandemic resilience; of global, national and intergenerational inequality; or of antibiotic resistance?

Probably the last undertaking to match this model was the Apollo mission in the 1960s, under the leadership of extraordinary individuals such as George Mueller, the head of Nasa’s Office of Manned Space Flight, and Gene Kranz, its chief flight director. And there were echoes of Oppenheimer’s work at Los Alamos – or at least its urgency – in the race to develop Covid vaccines and, in this country, in Kate Bingham’s leadership of the Vaccine Taskforce.

Dominic Cummings – wrong about so much else – was absolutely right that the government needed to take a lead once more in tackling the great problems of the age and “tapping distributed expertise”. The UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria) that he championed is now up and running; explicitly modelled on Darpa, the US agency founded in 1958 that (for instance) drove the development of the internet. But Cummings is long gone from Downing Street and Aria – however well-intentioned – is scarcely a priority for Rishi Sunak.

It has often been argued that the Manhattan Project faced a unique threat: the danger that the Nazis might develop an atomic bomb first. In a similar vein, the success of the Apollo mission is frequently ascribed solely to the specific pressures of the cold war. But such claims are a cop-out. The existential perils faced by humanity today are different to those of the 20th century but no less pressing – and certainly more numerous.

The true obstacle to new Manhattan Projects is the debasement of political culture. Modern populism recoils from intense strategic inquiries and state-of-the-art policy formulation: it thrives on the attribution of blame rather than the quest for solutions. Why pursue big ideas when you can persecute those in “small boats”?

Today’s politicians prosper in loud and transient news cycles. As Richard Fisher puts it in his recent book, The Long View: Why We Need to Transform How the World Sees Time: “The currency of political journalism is controversy: salient fights over issues in the present, with opposing actors, winners and losers.” In this context, governments have lost the ability and the hunger to marshal talent and put it to work in the service of grand, focused strategies.

One of the thinkers most favoured in the resurgent Labour Party is the economist Mariana Mazzucato. In Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism (2021), she writes that “what made [the moon landing] possible and successful was leadership by a government that had a vision, took risks to achieve it, put its money where its mouth was and collaborated widely with organisations willing to help”.

Exactly so. In a speech in February, Sir Keir Starmer framed his core ambitions for government as five key “missions”. Yet, in recent weeks, the prospective prime minister has seemed intent only on keeping the Labour rocket earthbound – especially in his panicked retreat from the green agenda after the Conservative victory in the Uxbridge and South Ruislip by-election.

In the last lap before the general election, nobody should begrudge Starmer a measure of caution. But there is a difference between caution and stasis. If he hopes to be a consequential prime minister, rather than simply an office-holder, he must turn his back definitively on the era of populism and its bogus claim that there are easy solutions to complex problems.

As John F Kennedy declared in his great speech at Rice University in September 1962: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

The horizon facing the next PM will be full of hard things. Most of them are global rather than narrowly domestic in character. We stand badly in need of the spirit of Oppenheimer’s Los Alamos, of the intensity and courage of Apollo’s mission control. Will our leaders recognise the urgency of the hour?