Some time at the beginning of the 1970s, James Baldwin asked me to take a taxi ride with him.

He was visiting my home town of Chicago. We met and, later, he asked me to travel to the airport with him.

For years, for decades, I erased that ride out of my mind. Thought for a time that it was a false memory, something I had made up, something my mind had dramatised, not an uncommon thing to happen to a person who writes plays.

And then, in the early 2000s, I visited the taxi ride briefly for something I published. After I wrote it, the memory faded again. Until about almost a year ago, when something told me to write about it again, write a book about it maybe.

I did not know then that next year would be the centenary of Baldwin’s birth. So maybe something in the air told me to do it.

I talked to a younger friend of mine about the man I call “Jimmy”. She is an African-American woman living in Europe, living on this side of the world like me. From Chicago, like me.

Unlike me, she studied Baldwin, still does. Her university intake in the late 1980s studied something called Afro Am, or African-American Studies as it came to be known.

Her professor at Berkeley specialised in it and so she’s read a lot of James Baldwin, knows a lot. So I asked her a couple of things.

I asked her if he would have been sipping bourbon or whiskey or whatever out of a paper cup as he talked to me in that taxi.

She said yes.

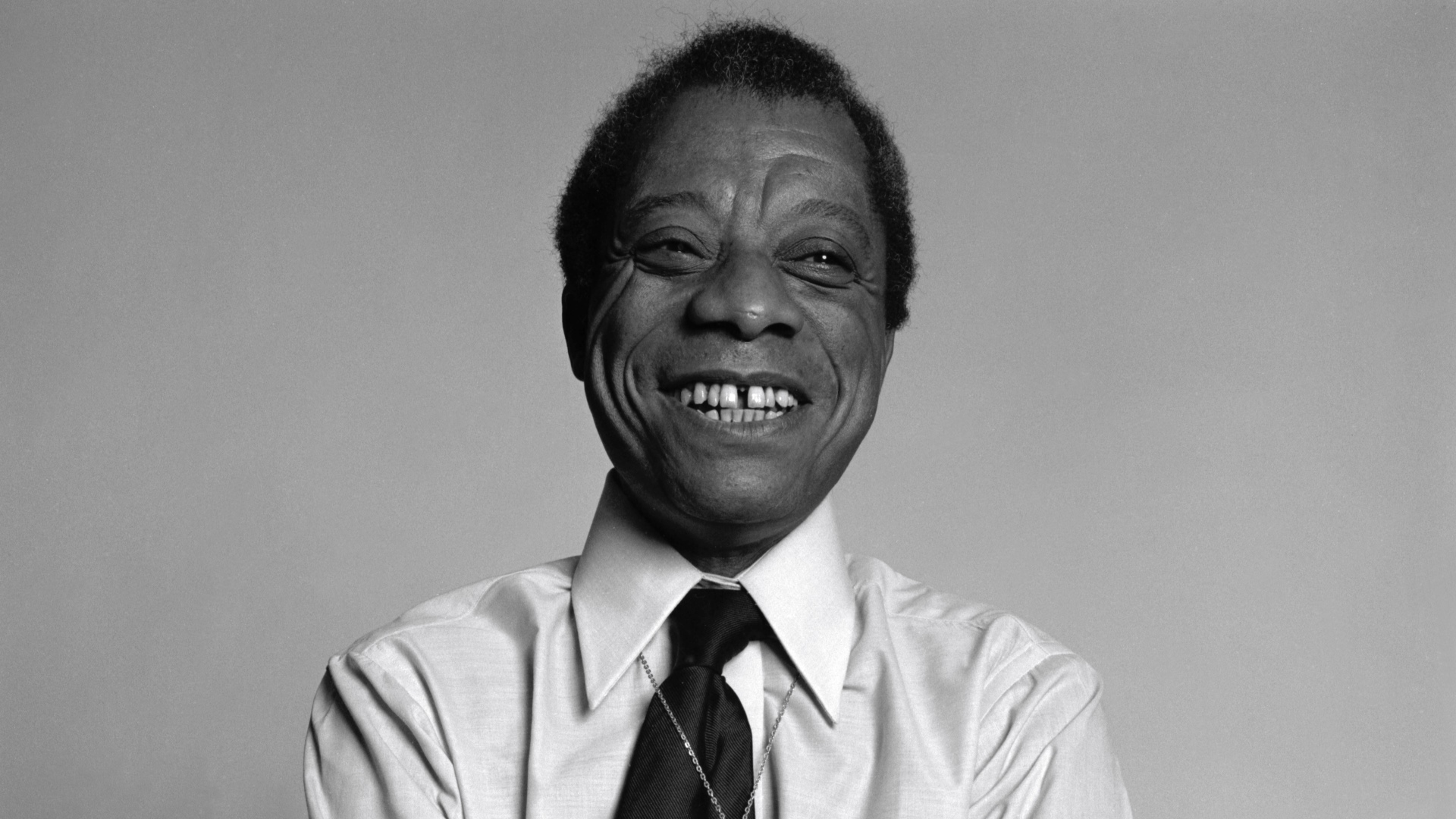

I asked her if he walked like a dancer and if he had a smile that covered his face, and she said yes.

I asked her if he would have cried as he talked to me, was he that kind of man, and she said, oh yes.

So what I’m writing about is an investigation, not only of that taxi ride, but of the era in which the taxi ride had taken place and even much, much earlier than that.

I was born a few days after Baldwin left the United States for Paris for the first time. Or rather fled to Paris; fled there so that he would not be arrested by the police for murder. Not a specific murder, but the one he had in his mind against those white people who denied him his human agency.

So he has been a part of my life all of my life.

I started reading his novels at a young age, and I know that this is true because I read his novel Another Country under the covers by flashlight. I am guessing that it belonged to my factory-worker dad, an autodidact and devoted to Baldwin.

I was astounded by that novel, and so when Baldwin sat next to me in the taxi cab on the way to the airport, weeping, something in me must have shut the whole experience down. Sealed it.

Baldwin is considered now to be an icon. A freedom fighter wailing against the forces of racism. And so he was. He understood completely the tragic irony of the United States, “the land of the free and the home of the brave”. Its essential absurdity.

Many people have pointed this out before, had said it before. But James Baldwin, who had been a preacher when he was a boy, knew that his job was to witness it, Christian witness it. Black witness it.

That meant “testimony”. What African Americans call “testifying”.

Baldwin had to speak out loud and to as many people as could hear him, and that is what he did with my generation.

But my generation, in many ways, was not present to hear him. Not everyone. But enough of us.

We, in some part, rejected him.

It took my friend’s generation: Generation X, the generations of my friend based in Brussels and her university teachers, to bring him back again.

What I am discovering, in re-reading his novels and essays and speeches and interviews, is the immense capacity not only of his mind, but of his humanity. His utter empathy.

There is in him, too, this driving, passionate, urgent search: for our common humanity.

He took no prisoners in this pursuit, because his prison is one in which it is necessary – a matter of urgency – to tell the truth.

I ask myself sometimes what he would make of the young of today. I think that he would be impressed. I think that he would be moved by them when they function at their highest: their care about the environment; other species; humanity. He would want to be a part of them, like he had wanted, he told me in the taxi, to be part of my generation.

So that he could be of service to us.

But I think his love for this new generation would come with a kind of health warning: not to become too attached to the necessity to triumph.

He would say to them, I think, to beware the need to excel at all costs. And the need to be seen.

Jimmy was completely devoted to the human spirit, especially as it ran within his people. Part of his fame came from extolling this.

It is easier now than in his day to become famous, to become a celebrity, to become known.

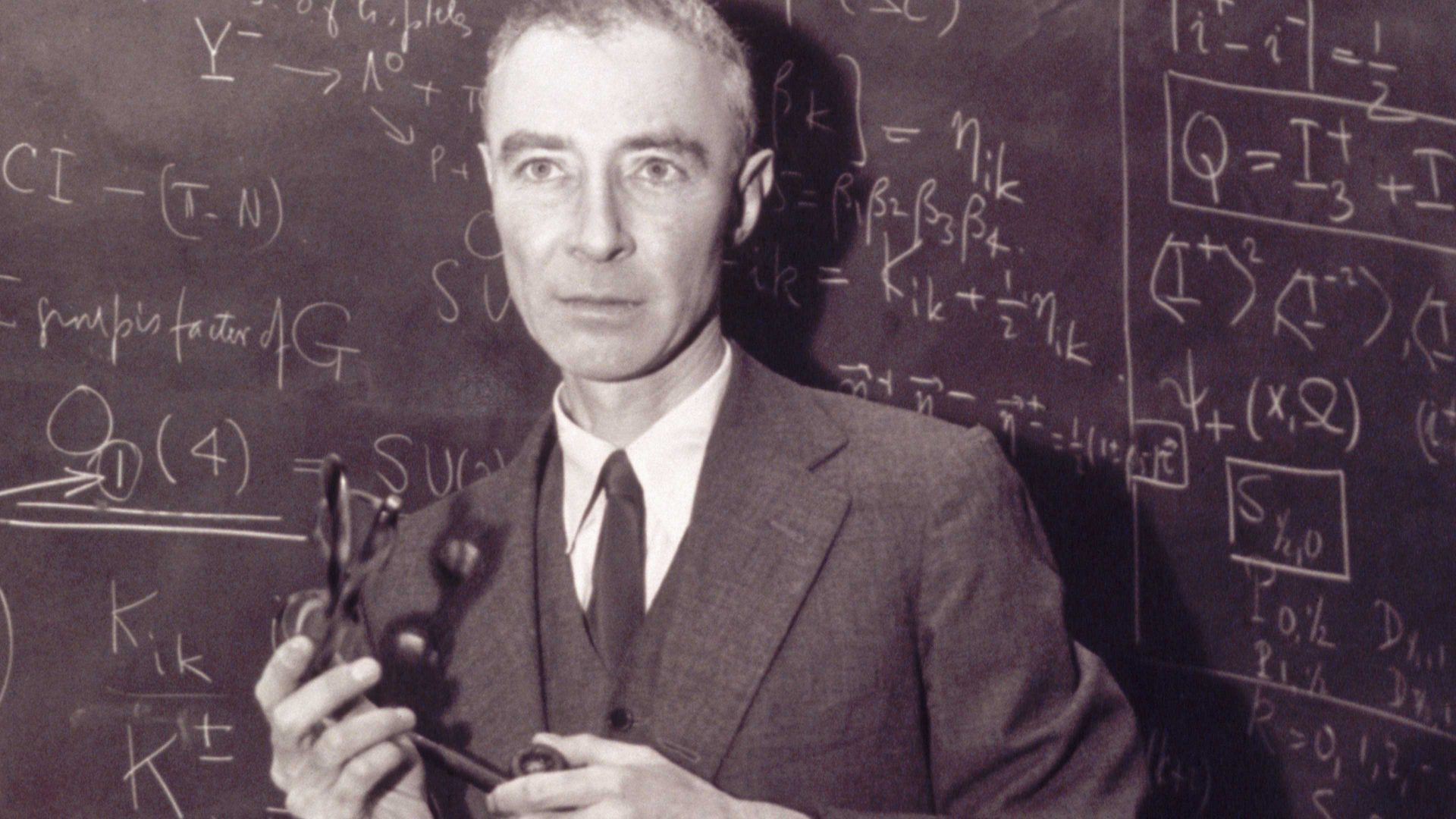

I think of James Baldwin and Robert Oppenheimer, for example, famous for their genius.

All of the group that were called “the prima donnas” of physics wanted, at the beginning, to be with Oppenheimer.

Everyone wanted to be on his team, to be commanded by him, to be lauded, understood by him.

And then one day Oppenheimer declared his humanity and, for him, it was over.

Part of what I’m exploring in my proposed book about Baldwin is how and why the fame and adulation and respect for him came, for a time, to an end.

What do we do with the geniuses who discover that genius is not enough?

That fame is not enough?

That what Baldwin called witnessing is the key, the core of our existence?

I think it is time for that new generation who are discovering the complex humanity, and the “witnessing” of Robert Oppenheimer, to discover James Baldwin.

Time for all of us.