As our interview begins, James Timpson is preoccupied at his desk, filling out a condolence card for the family of an employee who had recently passed away. If almost any other CEO had been “caught” doing that at the start of a media appearance, it would almost certainly come across as staged and in the worst possible taste.

Within just a few minutes of talking with Timpson, though, cynicism was banished: he had a brief minute in a busy schedule and wanted to get the card signed while he could.

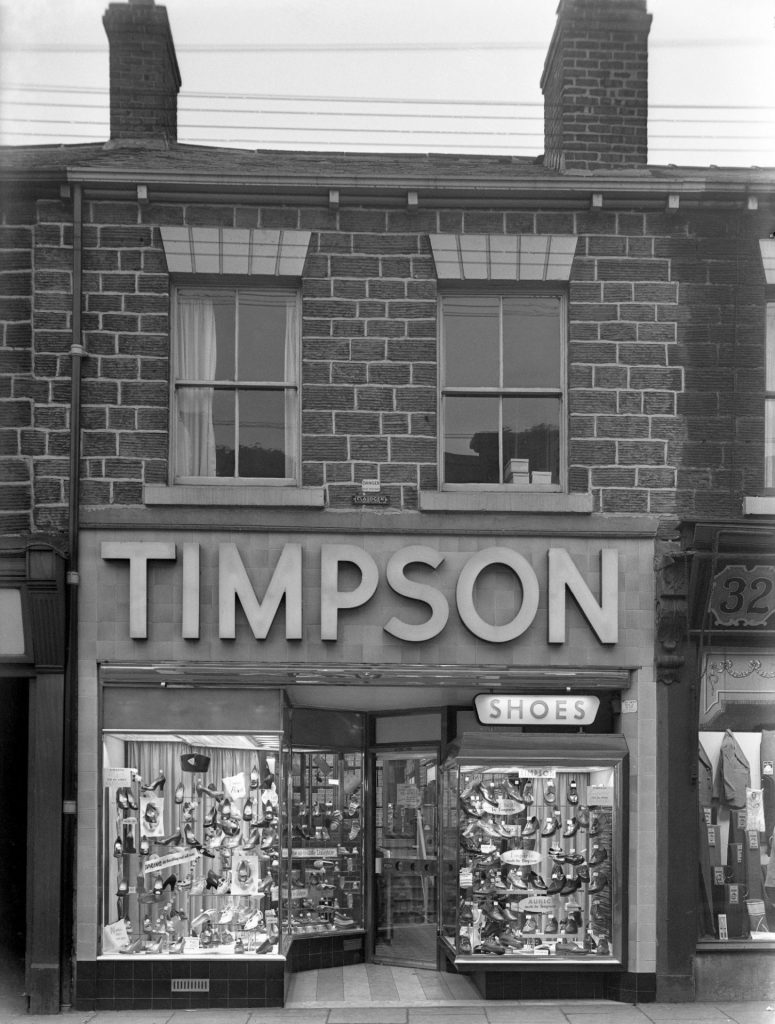

If you know one thing about Timpson’s, it’s that it’s the key cutters and shoe repair shop that’s still on most high streets – hardly a regular visit for most of us, but definitely very welcome when you need it. If you know a second thing about Timpson’s, though, it’s that the company has had a proactive policy of hiring reformed offenders from prison – so much so that they now make up around 10% of the staff, and fill out some of its senior roles.

This happened, as Timpson tells it, almost by chance initially. Just over 20 years ago, he and his wife were given a tour of a local paper, led by a guide called Matthew. He’d gone out to celebrate leaving school, and then “got into a fight, went to prison, thought his whole life was over,” Timpson recalls.

More than anything, on release Matthew wanted “a new job” but thought no one would give him one. Timpson offered him one on the spot, and kept his word.

Expanding that process did not work like a fairytale, Timpson recalls. At first, he hired people who hadn’t yet broken the cycle of offending, or who didn’t fit his usual hiring criteria. But once he had a process down, Timpson not only continued to regularly employ ex-offenders – he naturally sees the irony of hiring prisoners to cut keys – but also people still serving their sentences, albeit on day release (where you go to work, but come “home” to prison every night).

“The fact that we’ve got these people who have failed society, but in so many cases, society’s failed them. They’re good people. They’re no different from you or I,” he says.

Of the day releasers, he does add: “I’m sure their friends pop in and they use the phone and go to McDonald’s [during lunch break] and all that sort of stuff. But when they go to prison, they get their head down and go back to work the next morning.”

There is more to Timpson than just this heart-warming story of second chances, though. For one, the business empire is larger than you might expect: Timpson’s isn’t just the key-cutting company, but also encompasses Snappy Snaps, Johnson’s Cleaners, vending machines, and even a few hotels in France.

Notably, many of Timpson’s businesses are in industries everyone admits are in decline, if not outright dying – shoe repair “has been in decline since the 1960s,” Timpson notes – but they turn over £300m a year, and make £40m operating profit on that.

At a time when everyone says the high street is dying, Timpson appears to run an ethical business, making a profit, that treats its staff well. Given that, it is unsurprising he has now published a book giving advice on his methods – The Happy Index: Lessons in Upside Down Management.

The journalistic instinct upon reading, let alone writing, a paragraph like the one above is to start looking for what’s wrong with it, as when something sounds too good to be true it generally is. But if Timpson’s business has its demons, they are well hidden.

Working at Timpson’s might not be for everyone. The company has “fun days” of sorts, and a strict rule not to bring your politics into the office. There are days off and cash gifts upon getting married, having children (by whatever means), and even for pet adoption.

There is a company gym at head office, but the vending machines have all been replaced with fruit. Timpson’s perks come with a touch of paternalism, but given their retention rates that seems welcome to most of the company’s staff.

Timpson’s own commitment to his causes is also hard to doubt. At a time when there are endless stories about how the criminal justice system – especially prisons and the probation service – is falling apart, Timpson has quietly engineered a massive success story.

The UK releases prisoners from just over 90 prisons across the country. Working with the Ministry of Justice, Timpson has helped set up boards of local employers to liaise with officers and help find work for people as they come up for release. Within three years, every single release prison now has such a panel, and the employment rate for recent prison leavers has doubled.

Timpson acknowledges the win is a rare one under the current government administration, but is full of praise for the officials and ministers who worked with him to set up the initiative. His brother is the solicitor general of the government and has been a Tory MP for all of its recent iterations, though he is standing down at the next election.

Given the no-politics-at-work rule, and his own interactions with the government, does that factor into any of his work? “It’s unrelated, really,” is the unusually curt angle.

It would be a mistake to think of Timpson as someone solely motivated by altruism, though. It is clear he has a focus on what works and what doesn’t for his business. Almost everything within Timpson’s is the kind of business you need to be there for: shoe repair, key cutting, dry cleaning, photo printing, and which will benefit hugely from word of mouth when someone needs one of these services (which is generally infrequently).

As a result, each shop usually has only one member of staff, who runs it pretty much as their own independent business. There are no centralised records, no electronic tills feeding information back to HQ, and no strict rules as to what staff can and can’t allow. “About one in 25 of our customers a week, we do a job for free, that we could charge for,” he says (and this excludes offering free cleans to unemployed people with job interviews and the like).

“Our colleagues are given a lot, a huge amount of trust and flexibility. So they can adapt, rather than following ‘the computer says’, approach. They’ll try and find a way of doing it.”

This is particularly valued by staff hired from prison, he notes. “If you give someone lots of trust, especially someone who’s had that taken away, they value it greatly.”

HQ takes in sales figures and cash reports from the companies, but no more than that. But that doesn’t mean there is no attention to detail.

In his book, Timpson brags that he can say how much cash is in the business on any given day, to a high level of precision. Suspecting hyperbole, I ask him to do that during the interview – at which he agrees

to give the figure, provided I do not print it.

He gets it to within around £100 off the top of his head, and within a few seconds more reads it to the nearest pound from a note by his hand on the desk. The business can only do good for communities if it is on a sound financial footing itself, after all.

As our conversation comes to a close, I note that while lots of how Timpson’s is run – high-tech gym, enlightened hiring, and the like – could be framed as modern, when talking to him it feels extremely old-fashioned.

In the Victorian era, the idea of the responsible business owner came to the fore, particularly in the ethos of Quaker confectioners like Fry’s, Rowntree’s and Cadbury (even if the process by which their key ingredient was obtained was reprehensible).

Factory owners had a sense of responsibility for their employees, often going so far as to build homes, schools and community infrastructure primarily for those families.

This often came with a moralising edge – many banned drinking and other “immoral” behaviour, extending their control outside working hours. Cynics also note that such efforts made it hard for people to switch jobs.

But in the generous view, such efforts to make working for such a company a shared endeavour in which the benefits reached everyone, there is a resemblance between these Victorian patriarchs and Timpson. It is not one he rejects.

“They were like… maverick personalities,” he said. “They tried to sort of circumvent government where government was failing. They just took their business and tried to fix it.”

Is Timpson’s, with headquarters in the north and stores on thousands of “failing” high streets trying to do the same in a very different era, then, I ask.

“In our own way, yes,” he concludes. “But it only works if it benefits the business as well.

“Otherwise, you know, we do give money to lots of charities, and we’re very philanthropic. But the best philanthropy we do is giving jobs to people who wouldn’t get a job.”

The Happy Index: Lessons In Upside Down Management is out now, published by HarperCollins