“One conquers the world, one dominates it, one uses it; thus, quiet and proud, a beautiful fish circles in this bowl.”

This challenging, lovely sentence was written 100 years ago, during the birth of surrealism, a movement then rooted in poetry and literature but beginning to spread out into painting and sculpture. Typeset on a single sheet of blue A4 paper with the heading Blue 1, it was one of six answers – to unknown questions – in a tract by Paul Nougé (1895-1967), a Belgian biochemist and writer whose view of the nascent movement was already diverging from those of his peers.

Nougé, whose influence on surrealism is acknowledged in one of two exhibitions dedicated to its centenary, sent his tract, dated November 22, 1924, to 100 chosen recipients. A clue to how he felt about the whirlwind of creativity he had been caught up in came in the fourth response: “Watching games of chess, or ball, or the seven arts may amuse us a bit, but the emergence of a new art is hardly our concern. Art, anyway, has been demobilised, what matters is to live.”

There was a rankled edge to Nougé’s words. In France, a “new art” was indeed emerging, led by the writer and poet André Breton (1896-1966), later dubbed the “Pope of surrealism”.

Nougé and Breton, future adversaries, are likely to have met up during military service in the first world war. Breton, a medical student, had been enlisted as a medical orderly. Nougé was deployed as a chemist, his lifelong profession.

Both witnessed human suffering during the war and it affected their postwar writing; Breton, influenced by the psychoanalytic theories of Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, explored dream-thoughts, the unconscious, and automatic writing as he developed his template for a movement that brought the fantastical and the illogical to art and literature.

Nougé’s form of surrealism ignored Freud and other Breton obsessions, (the occult, alchemy) taking a different, more rational path. His interest lay in Cartesian theory – rooted in the separation of mind and matter and led by 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes – with emphasis on the experimental language of poetry and prose.

The Belgian-American critic Lucy Sante has written that Nougé “believed that the task of poetry… was to disturb mental habits, to break the template of conventional thought that kept people imprisoned in their lives. He believed that by pushing relentlessly on the pillars of cognitive convention, they would eventually give way.”

In France, a few weeks before Nougé’s first tract was distributed, Breton’s surrealist group was established with his publication of Manifestes du surréalisme (Manifesto of surrealism). He defined surrealism as “pure psychic automatism”, letting go of realism and reality.

He was not alone; the French-German poet Yvan Goll, leading another rival group of surrealists, launched his Manifestes du surréalisme too. It was published two weeks before Nougé’s tract, and a week before the first issue of the French surrealists’ publication La Révolution surréaliste on December 1, 1924.

In France, under the collective Bureau de Recherches Surréalistes (Bureau of Surrealist Research) a “Declaration of 27 January 1925” signed by 26 writers and artists, including Breton, was published to establish a revolution to liberate the mind. “Surrealism is not a poetic form,” it stated. “It is a cry of the mind turning back on itself.” The rifts between the surrealism of Nougé and Breton were widening.

The term “surrealist” was devised in 1917 by French writer Guillaume Apollinaire, (1880-1918) promoting the idea of a “new spirit”. The baton was then taken up by the Dadaists, an anti-establishment movement of dissent and disorder, founded in 1916 in Zürich. After Dada was disbanded in 1919, many members became surrealists, spreading out worldwide.

Nougé, a quiet man, never put himself forward to lead the Brussels group of surrealists but he was its intellectual leader. As a biochemist – he held a full-time job until 1953 – he preferred anonymity, to think, to write and let others in Belgian groups explore surrealism in prose, poetry and art – as they would to such shocking and remarkable effect.

At one point he refused to even use the word “surrealism”, wanting it deleted from a gallery show of surrealist art. He disliked the commercialism attached to the term.

However, he continued to promote the art of his friend, the Belgian-born surrealist René Magritte (1898-1967). Magritte’s aesthetic, putting familiar objects into unfamiliar surroundings, was a visual interpretation of Nougé’s literary interventions.

In a tight-knit group, Nougé worked with writer and photographer Camille Goemans and poet Marcel Lecomte, founding the periodical Correspondences in 1924. Later the three were joined by the musician and composer Paul Hooreman – for a short period – and poet-musician André Souris, linking literary and musical experimentation.

The trio – with emphasis on anonymity – delivered leaflets of remarkable originality, each one printed specifically on a different coloured paper. The one-page tracts laid the foundation for surrealist interventions in literary works.

The first, which expressed that disinterest in “new art”, began a series of 22 tracts. Around 100 copies of each were distributed to chosen recipients until June 20, 1925.

“We’re looking for accomplices,” wrote Nougé. But he was not overly concerned about his theories becoming widespread, or about reaching out to others of a similar mind. The provocative texts challenged past and current literary thought, from Socrates to Marcel Proust, André Gide and the French surrealists. Tract “Orange 19” was dedicated to Breton.

Under Nougé’s influence, surrealism in Belgium maintained its literary background, continuously questioning, rather like a scientific experiment. Nougé commented: “Before being a doctrine, surrealism is fundamentally an attitude of mind.”

And in 1927 the Belgian surrealists broke with French surrealists altogether, rejecting their focus on Freudian theories and automatic writing. Nougé stated that the Belgian movement was “an ethic based on a psychology coloured by mysticism.” The same year Magritte painted a fractured double-image Portrait of Paul Nougé.

Magritte, following in the footsteps of the eerie, nocturnal works of self-taught Symbolist painter Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946), constantly questioned pictorial representation. “Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see,” he explained.

His amusing, disturbing The Cut-Glass Bath (Giraffe in a glass), 1946, confirms this viewpoint. The first known version illustrated a new edition of poems entitled Les Nécessités de la vie et les consequences des rêves précédés d’Exemples (The Necessities of Life and the Consequences of Dreams) originally published in 1921, by Magritte’s friend, the French-born surrealist and poet Paul Éluard.

Now, in the centenary year of surrealism, Magritte’s artwork has been chosen to promote Histoire de ne pas rire: Surrealism in Belgium, one of two major explorations of the movement being held in Brussels.

At the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, the spectacular IMAGINE! 100 Years of International Surrealism tells the more familiar story and focuses on the international surrealists, showing around 140 exhibits.

It opens with Breton, and links fin-de-siecle Symbolist works such as Sleeping Medusa, 1896, by Fernand Khnopff with the emergence of surrealism. The Fireside Angel (The Triumph of surrealism), 1937, and Birth of a Galaxy, 1969, by Max Ernst are here, and naturally so are Marcel Duchamp with La Boîte-en-Valise (Box in a Suitcase), 1935-41, as well as Salvador Dalí’s Soft Construction with Boiled Beans, 1936, and The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 1946.

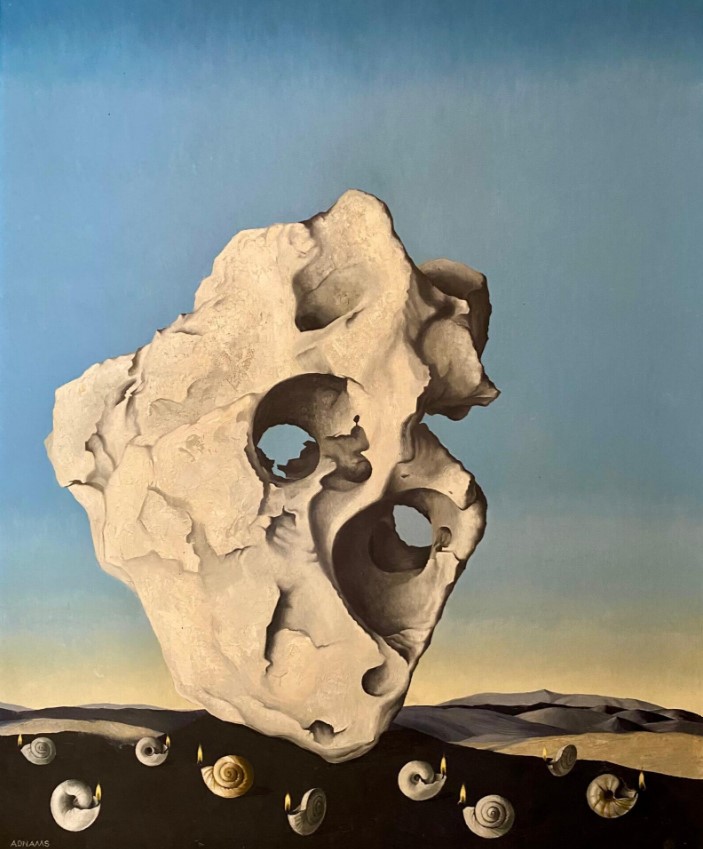

The contributions exemplify surrealist thought expressed visually, as in Soulless Children, 1964, by Cuban artist Wilfredo Lam (1902-82) who emigrated to Paris in 1938. Dora Maar’s cryptic photomontage Sans Titre (Main-coquillage), 1934, and Dorothea Tanning’s A Very Happy Picture, 1947, mix with works by Alexander Calder, Alberto Giacometti, and the English artist Marion Adnams (1898-1995) with her enigmatic A Candle of Understanding in Thine Heart, 1964. The works of 17 female artists are included.

Nougé’s fleeting but vital contribution to the story of surrealism is to be found around the corner at Bozar (Brussels Centre for Fine Arts), where curator Xavier Canonne titles his history of 75 years of Belgian surrealism Histoire de ne pas rire (Story with No Laughs) – a phrase taken from Nougé’s writings.

Canonne calls Nougé the “brains” of the Brussels surrealist group and explains how humour, as a subversive strategy, was a Belgian surrealist trademark. The 260 artworks and over 100 documents in the exhibition explore this narrative, tracking the expanding ideas of the Belgian surrealists and showing how they diverted from the mainstream.

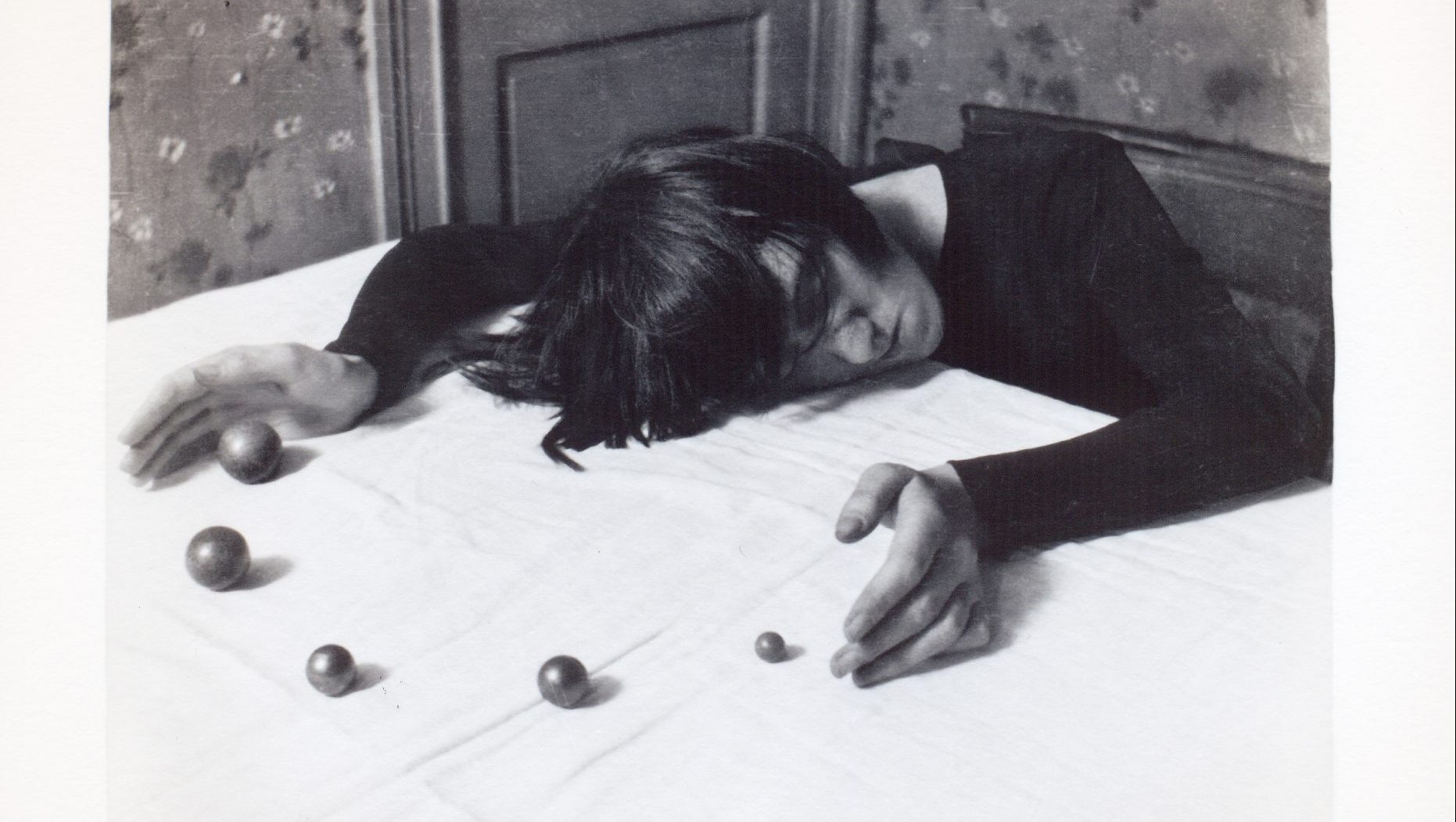

Nougé’s The Juggler from the series Subversion of images, 1929-1930, reveals him to be an adept, creative photographer. The literature, including Nougé’s Correspondence, 1924-25, and the magazines Oesophage, 1925, and Marie, 1926, is a surrealist feast. Among the artworks is The Drop of Water, 1967, by French-born Belgian surrealist Jane Graverol (1905-84) in which the Belgian surrealists, including Nougé, are portrayed.

In 1929, Nougé wrote to Breton: “I would like it if those among us whose names are getting to be known a bit would step aside.” There was little chance of this on Breton’s side; while he never attained the wealth and international celebrity that Dalí and Magritte achieved through their surrealist paintings, his willingness to be credited as the instigator of surrealism makes him remembered as a major figure in 20th-century art.

Nougé, meanwhile, lived in obscurity, publishing little and being best known for collaborating with and influencing Magritte. Their friendship though would dissolve over a feud in the early 1960s.

After Breton died in 1966, surrealism was officially dissolved in France with the publication of a death certificate in Le Monde newspaper. No such dramatic pronouncements followed Nougé’s own death, in Brussels, a year later, and his vision of surrealism has remained firmly in the shadows of the movement’s giants. Until now.

Histoire de ne pas rire: surrealism in Belgium is at Bozar, the Centre for Fine Arts, rue Ravensteinstraat 23, Brussels until June 16. IMAGINE! 100 Years of International surrealism is at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, rue de la régence 3, Brussels until July 16, then touring to Paris, Madrid and Hamburg from September 2024 to October 2025