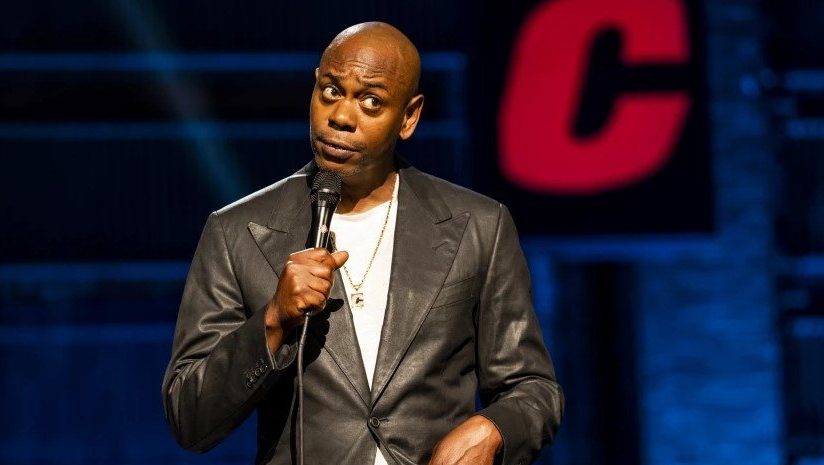

When the stand-up David Chappelle wanted to signal where he stood on the gender war, he only needed to drop one name: JK Rowling. “They cancelled JK Rowling,” he says in his latest Netflix special, The Closer, incredulously.

“They cancelled her because effectually she said gender was a fact… I agree. I agree, man. Gender is a fact.”

Chappelle declared himself “team terf ” – an acronym for “trans exclusionary radical feminist”, used derisively (and frequently in combination with abuse or threats) about those who critique the concept of gender identity.

Although The Closer includes jokes about women in general, lesbians specifically, poor white people as a whole, and Jews, it’s this section that sparked outrage. A small number of staff at Netflix were appalled enough to stage a walkout.

Since the show landed, there has been a torrent of articles expressing affront at Chappelle’s alleged transphobia, all prominently citing his endorsement of Rowling. One woman could stand as a shorthand for the entirety of “terfdom”.

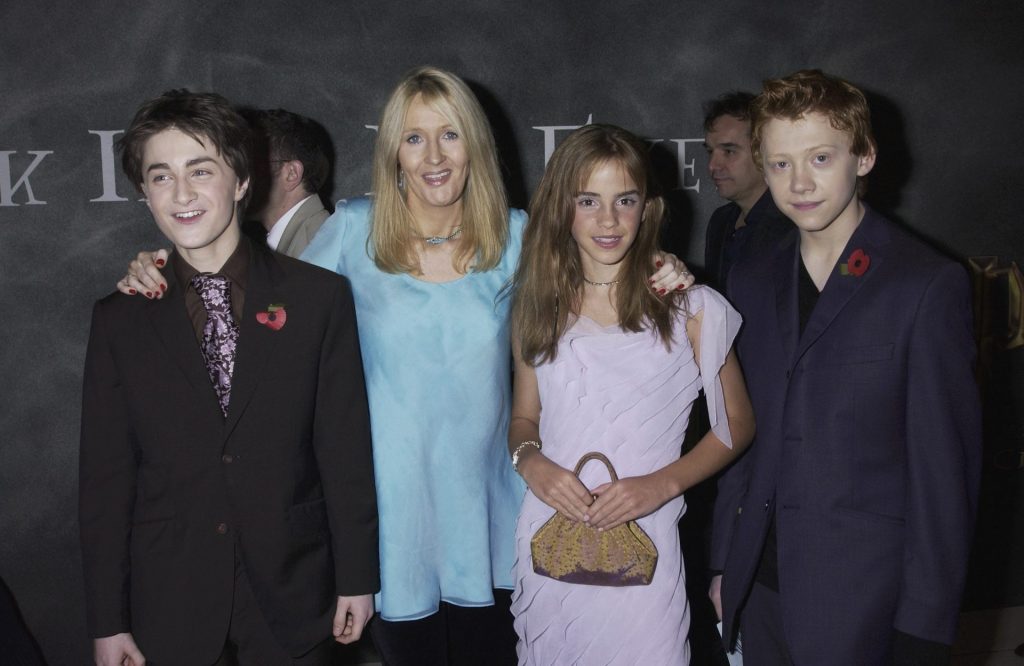

Rowling’s public profile has always been political, but until 2019, those politics were not the kind to turn her into an international hate figure. Ever since the Harry Potter series launched her into extraordinary fame – and astonishing wealth – she has lent quietly and consistently to the left. Most famously, and strikingly, she has refused to use tax-minimisation schemes to guard her wealth: in 2018-19, she received over £100million from royalties and other sources, and paid out £48.6million to the treasury.

That commitment to giving her share to the state is informed by her early experience of harsh poverty as a single mother in the 1990s. “I remember nights when there was literally no money,” she has said of life with her daughter after the break up of her first marriage.

“There’d been nights when I had one biscuit and that was dinner,” she said. Her initial advance for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was a modest £2,500, but to her, it felt like a “fortune”.

Since then, she’s believed to have made more than £1billion from her writing, and a further £200million from the film adaptations. It was hardly a painless path to success – she had to contend with denunciations and book burnings from evangelicals horrified by the supernatural content of the stories – but even as a higher-rate taxpayer, it has left her with substantial wealth.

Out of that, she has made generous donations both to the Labour Party and various charities. Her own charity, Lumos, was founded in 2006 after Rowling was shocked by the number of children being abandoned in orphanages in Moldova. It now works around the world to support families.

A few of her interventions were more contentious, however.

In 2014, she supported the unionist Better Together campaign in the Scottish independence referendum. Breaking up the UK, she said, would be “a historically bad mistake,” and she backed up her words with a hefty donation. Scottish nationalists on Twitter called her a “cowbag”, a “bitch” and worse in response.

Rowling also opposed Brexit – her frustration with what she saw as Jeremy Corbyn’s lack of leadership in the Remain campaign was one of the reasons she publicly criticised his leadership of Labour. That stance, too, led to trolling.

But those controversies could not dint her stature as a well-regarded public figure. It would have been laughable had anyone suggested three years ago that Rowling would come to be seen as the public face of social conservatism, disowned by her fans and denounced by the actors who became famous as the characters she wrote.

For that to happen, it would take an issue of staggering toxicity and an atmosphere of extraordinary moral certainty. For that to happen, it would take a collision with the trans activist movement.

Rowling’s position in the gender wars first began to emerge publicly in 2018. This was relatively late: the feminist journalist Julie Bindel had been covering the issue in the UK since the 2000s, and other writers gradually entered the fray thereafter.

There had been a steady increase in interest since 2016, when the Women and Equalities Committee published its report into transgender equality. This adopted several activist demands, including calling for gender to be legally recognised on the basis of self-identification rather than requiring the approval of experts.

It’s worth pausing here to look at exactly why self-ID is such a flashpoint. In the UK at present, the process of legally changing gender is governed by the Gender Recognition Act 2004. Anyone born male who wishes to be officially recognised as female, or born female who wishes to be officially recognised as male, needs to obtain a gender recognition certificate (GRC). Applicants must present evidence that they have a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (discomfort with their birth gender), that they have lived in their acquired gender for two years, and that they contend to live as that gender for the rest of their life.

Trans people have complained that this process is bureaucratic, intrusive and impersonal: applicants never meet the panel assessing them face-to-face.

Moreover, there is resentment of the idea that anyone other than the individual in question should be the arbiter of their identity. James Morton, of the Scottish Transgender Alliance, told the Women and Equalities Committee that “a number of trans people have been really traumatised and humiliated by the process.”

The proposed alternative would eliminate the demand for evidence, and instead issue a GRC to any individual who says they require one. For trans activists such as Shon Faye, writing in her book The Transgender Issue, this would be a “simple legislative change” that would make obtaining a GRC process “more accessible and less pathologising”. Faye claims that a similar process is already in place in several European countries, with no evidence of any ill-effects.

But such arguments have failed to satisfy sceptics on the self-ID issue. If gender becomes legally a question of what you say you are, it is impossible for anyone else to say that you’re not. This is a problem for any service, group or institution intended to serve one sex only.

Should a male person who states that they are a woman have access to women’s changing rooms? Women’s toilets? Women’s sports? Women’s refuges? Women’s prisons? Women’s prizes? Women-only shortlists?

All these have been established in response to the sex-based disadvantages faced by women – whether the threat of voyeurism from creepy men, the unequal physical size and strength of the sexes, or the under-representation of women in professions and politics. The fact that an individual is unhappy with their sex does not necessarily mean that sex becomes irrelevant for all purposes.

“If we think there are good reasons to retain same-sex spaces generally… these reasons don’t cease to operate when males self-identify as women,” writes the philosopher Kathleen Stock.

Experience has shown the legitimacy of such concerns. Cases such as that of Karen White – a male rapist who identified as a woman and was placed in a women’s prison (despite not having a GRC), and who went on to sexually assault women inmates – show that the embrace of gender identity can have real and damaging consequences for women.

Another important factor is that the definition of “trans” has changed dramatically since the GRA was introduced less than two decades ago. In 2004, the phrase “trans person” was rarely used – instead, the concept of “transition” was understood to refer to transsexuals, meaning people who had altered their sexual characteristics to live as the opposite sex. Think of the British author Jan Morris (who described her transition from male to female in her 1974 book Conundrum) or the American porn star Buck Angel, who both used surgery and hormones to better fit their bodies to their self-perception.

But during the 2010s, that understanding began to be seen as outdated. Increasingly, it was claimed that requiring someone to undergo surgery in order to be recognised as their “true self ” was unreasonable. GRCs had been designed as a way to give legal status to people who had physically “changed sex”; now, activists began to argue that making someone’s gender status contingent on surgery that effectively rendered them sterile by removing reproductive organs amounted to “forced sterilisation”.

In other words, having a fully functioning penis should be no barrier to being a woman.

So, if feminism was supposed to help the most vulnerable women, should that not include trans women? And if that was the case, wasn’t it an act of “cis privilege” (cis meaning not trans) to focus on female physical experiences inaccessible to trans women?

After the 2017 Women’s March to protest the election of Donald Trump, trans writer Katelyn Burns complained that she had been “excluded” by “vagina-centric rhetoric”. On the other hand, you had to take into account the people with vaginas who didn’t consider themselves to be women at all. Better, perhaps to avoid the word “woman” altogether.

Which brings us back to Rowling. On June 6 last year, she tweeted a link to a news story referring to “people who menstruate” in the headline. (This is one of a suite of circumlocutions designed to avoid the word woman. Others include “pregnant people” and “people with cervixes”, although terms for men such as “prostate havers” have so far failed to take hold.) Alongside it, she wrote: “‘People who menstruate’. I’m sure there used to be a word for those people. Someone help me out. Wumben? Wimpund? Woomud?”

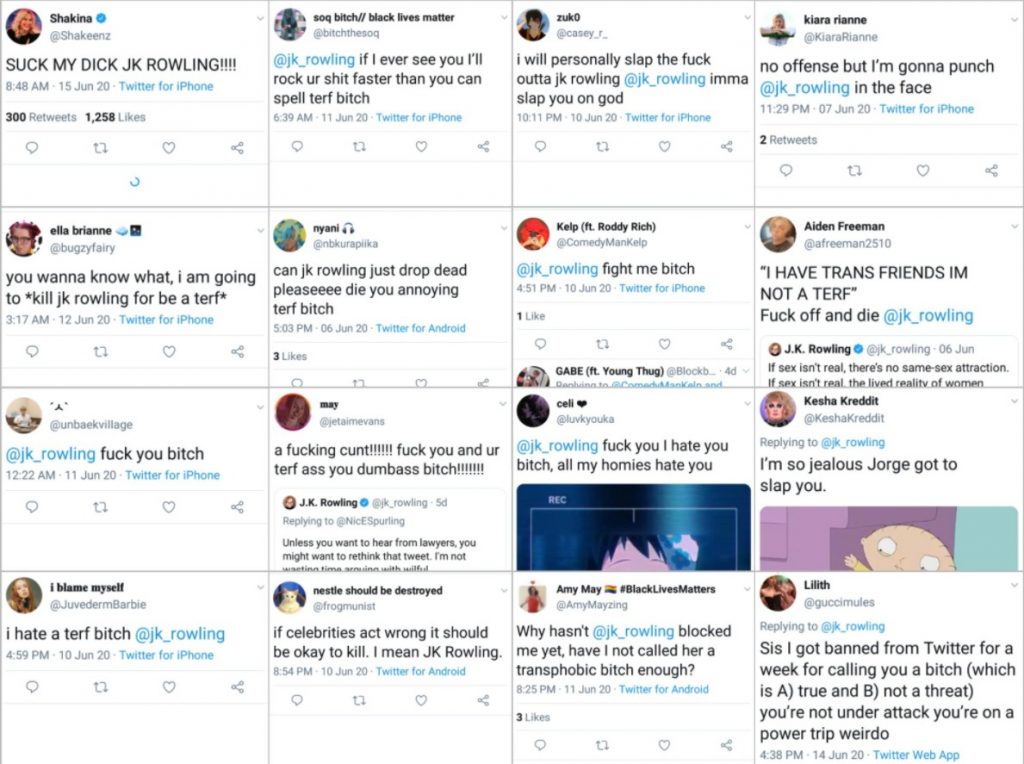

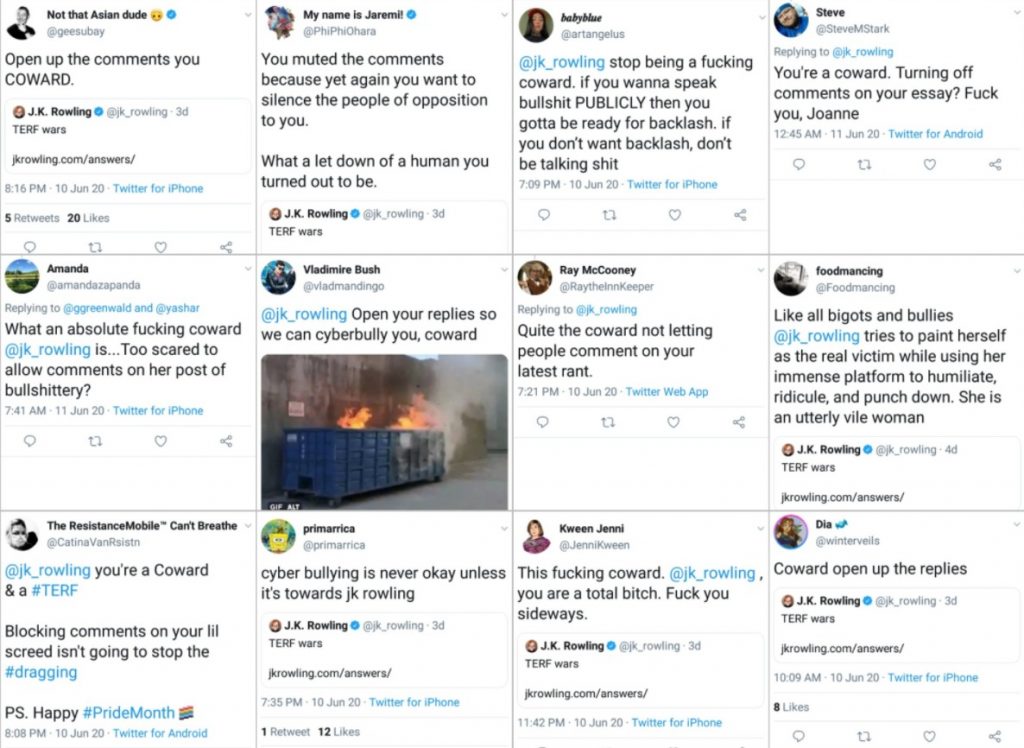

Variety described this as an “antitrans tweet”. NBC was more circumspect: saying she had been “accused of transphobia”. Those accusations took the form of thousands of furious social media posts – many containing horrific abuse and threats – all of which were of the opinion that wanting to use the word “woman” was an appalling affront to the trans community.

This hadn’t been Rowling’s first statement on the issue. The previous December, she had shared her support for Maya Forstater, a thinktank employee who lost her job after tweeting about her gender critical views (the term “gender critical” has been adopted by those who are critical of replacing the concept of sex with self-defined gender in policy and law). “Dress however you please. Call yourself whatever you like. Sleep with any consenting adult who’ll have you. Live your best life in peace and security. But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real?

#IStandWithMaya #ThisIsNotADrill,” Rowling tweeted. That time, Rowling’s detractors chose to patronise her as an essentially clueless, rather than malicious, woman. In 2020, though, she followed up with a detailed post on her website. She reiterated her support for trans people and her belief they should be able to live free from harassment; but she also revealed that as a survivor of an abusive marriage, she knew the cost of male violence, and did not want to see sex-based protections for women and girls dismantled.

It was an intimate and considered piece of writing that should have inspired sympathy even among those who disagreed. Instead, it lit a bonfire of condemnation. By the end of 2020, all three main Harry Potter stars had either directly condemned or unambiguously distanced themselves from Rowling: none offered support to her as a victim of domestic violence.

Potter fan sites hurried to assert their support for the trans cause, and opposition to the creator of the work they loved. If you visit The Leaky Cauldron, you’re greeted by a lightning bolt logo decked out in the pink and blue of the trans flag.

Even when Rowling was not being outright abused and ostracised, the best she could expect was to be pathologised: a profile in New York magazine asked “Who Did JK Rowling Become?” and concluded that she was a woman so scarred by fame that she had lost the ability to feel sympathy for anyone outside her immediate experience. Only psychological damage could explain why a woman whose politics had previously been “comfortably center left” could have embarked on a path which was – to her detractors – selfevidently bigoted and cruel.

But it’s not true to say that Rowling’s politics have always been “comfortable”. As her engagements on Indyref, Corbyn and Brexit show, she was very willing to get her hands dirty when she felt it was required.

Part of the severity of the backlash to her stems from the fact that – in the first two cases – she aligned herself against lost causes for which trans rights have subsequently become a proxy battle. In the case of Scottish independence, going further than Westminster on trans issues has been a way for the SNP to show its reforming credentials, while in the post-Corbyn Labour left, trans rights have been adopted as a badge of distinction.

This only helps to explain some of the reaction in the UK, though. The extremity of the global condemnation of Rowling has to be understood in the context of who she is. As the creator of a generation’s most beloved character, Rowling was not just treasured, but coveted. There was a feeling that she somehow belonged to her fans.

Her failure to take the required line was experienced as more than a disappointment. It was a crushing betrayal by a symbolic mother.

Rowling’s beliefs are that sex is real, that male violence is a problem, that women should be able to talk about themselves in clear language, and that no woman should lose her job for expressing such opinions. No critics have convincingly explained why believing these things hurts trans people.

The rage against Rowling is actually rage against her for being a woman who has not politely faded into the background, but who has instead asserted her voice and her boundaries. That is what is specifically infuriating about her – and it’s why one of the favoured tactics from her attackers was to reply to her tweets with images of pornography.

The sexual nature of the violation was not accidental. But Rowling has not buckled under the abuse. She is, for now, the inadvertent figurehead of a highly contentious issue; but she is too much her own woman to be reduced to a caricature by anyone.

- What do you think? Email your views to letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

- Become a member of The New European community by taking out a print and/or digital subscription from just £2.30 a week.