Jacques Becker had a vision. By the summer of 1953 the filmmaker, who’d

served his apprenticeship as assistant to Jean Renoir during the 1930s, had seen enough of French directors aping the noir thrillers coming out of the United States. He knew there was potential for a specifically French kind of

crime thriller that didn’t parrot tropes imported directly from across the Atlantic because France had the stories, characters, locations, actors and, most importantly, the mindset to create something unique to itself.

He’d written a screenplay adapted from Albert Simonin’s novel Touchez pas

au grisbi, a title that translates loosely as Hands Off the Loot, and had already

secured Jean Gabin for the lead role. One of France’s biggest stars of the 1930s, Gabin was approaching 50 and struggling to find roles suitable for an

aging matinée idol. In Max, the former gangster drawn back into the Parisian underworld by events beyond his control, Gabin saw an opportunity to restart his ailing career.

When casting Angelo, the aspiring big-time gangster who becomes Max’s

nemesis, Becker knew precisely what he wanted for the role but not who.

Someone intimidating, someone with the look of an Italian, someone with

charisma.

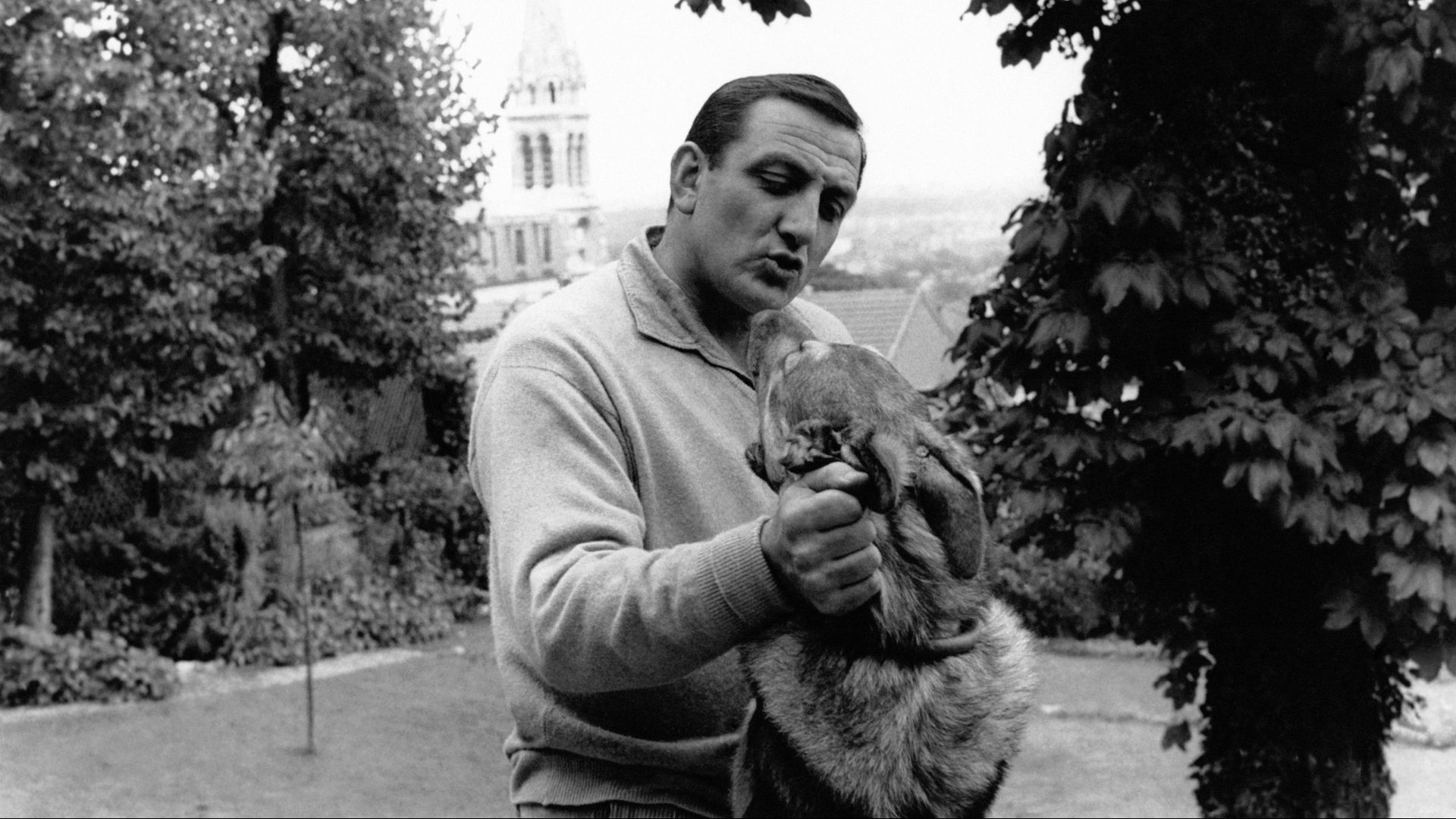

His scouting mission took him to the regular wrestling card at the Salle Wagram in Paris, which is where he first set eyes on promoter and former

champion wrestler Lino Ventura. Italian-born but raised in France, Ventura had the physique Becker was seeking and, with his fight-flattened nose, strong jaw and dark, hooded eyes, exactly the kind of gangster look that he

envisioned for Angelo.

When Becker asked Ventura to come in for a meeting, the 34-year-old arrived

clutching a folder of photographs of the wrestlers and boxers in his stable.

“I had gone to see Becker believing that he was interested in my roster but he asked me if I wanted to be in films,” recalled Ventura. “I said no.”

Certain he’d found his Angelo, Becker used everything in his power to convince Ventura to take the part. When his quarry plucked an astronomical

figure out of the air as the fee he’d require, Becker agreed, but it was the chance to work with the great Jean Gabin that really clinched the deal.

A film set was a different world to the fetid, smoke-filled halls that Ventura was used to. On his first day he was understandably anxious and uncharacteristically aggressive. As he left for the studios in Boulogne with his suitcase he told his wife, “The first person to get on my nerves gets my

hand in their face then I’m coming straight home”.

It was Gabin who put him at his ease immediately, even after Ventura had barged unannounced into the star’s dressing room within moments of arriving on set. There was an instant chemistry between the pair that transferred first onto the screen in Touchez pas au grisbi, then into four more films together and into a friendship that lasted until Gabin’s death in 1976.

Despite Ventura’s ill-judged first approach, the veteran star had immediately seen something in the lumbering colossus stammering a clumsy introduction.

“Screen presence in cinema is undefinable,” Gabin said of his co-star. “You can have people who are hugely gifted but unfortunately don’t have the presence or charisma to succeed like an actor who has both. It is not something that can be learned”.

Touchez pas au grisbi was a huge success, kickstarting Gabin’s career and

launching Lino Ventura to stardom. The film established an essentially French style of noir that blurred the moral lines between policemen and criminals and left a legacy still felt today: Martin Scorsese cited the film as a key influence on his 2019 movie The Irishman.

Becker’s film also established Ventura as one of European cinema’s great tough guys, whether playing a criminal, policeman or Resistance leader. The

film policier (thriller) suited him perfectly, more character-led than plot-driven, more interested in the psychology of criminals and those seeking to catch them than shoot-outs and car chases. For all his boxer’s nose and wrestler’s biceps there were layers to Ventura that made him a surprisingly

nuanced screen presence.

It took until the 1980s and a memorable performance as Jean Valjean in an adaptation of Les Misérables for Ventura to break out from a litany of firm-but-fair gangsters and world-weary detectives, meaning he never matched the international celebrity of more versatile contemporaries like Gabin, Alain Delon and Jean-Paul Belmondo.

He was a household name in France though, and his sudden death from a

heart attack at the age of 68 shocked the nation. The archetypal gentle giant,

Ventura was almost as popular for his charitable activities resulting from close family experience of disability as for his screen appearances. Indeed, once he was financially secure, Ventura’s film work became almost a sideline to the charity positions he took on, after one of his daughters was born with a disability. During the last three years of his life he turned down all offers in favour of overseeing the construction of specially adapted homes by the Perce-Neige (Snowdrop) foundation he’d started with his wife, Odette.

Ventura was eight years old when he arrived in Paris from his home town of

Parma with his mother, to join his father, who had left for France when Mussolini came to power. He had established himself as a salesman in the

French capital before sending for his family. Giovanni Ventura died soon after their arrival and Lino’s formal education ended then, at the age of nine, and he took on a string of different jobs to help put food on the table.

Away from work, two things kept Ventura occupied and away from malign

influences that could have tempted a street kid into a life of crime. He adored the cinema and would sit for hours looking up at the flickering screen, on one occasion claiming to have seen eight films in one day. His physical prowess also drew him towards wrestling.

“I owe a great deal to sport because it saved me from a lot of things,” he said.

“Sport gave me the opportunity to meet some extraordinary people.”

His ring reputation grew quickly, allowing Ventura to turn professional and, despite the war claiming what would have been his peak years, in 1950 he became the middleweight Greco-Roman wrestling champion of Europe.

He didn’t have long to enjoy his title, however, suffering a career-ending

broken leg in his first defence.

Reluctant to leave the sport that had hauled him out of poverty Ventura

moved into promotion, becoming a familiar figure, limping around the

venues of Paris while also helping Odette to establish a successful children’s clothing business.

He’d always been a grafter, always bounced back from every setback, always lived on his wits, but this felt different. This felt like a future. As Lino Ventura set off for the Salle Wagram one summer evening three years after the cruellest of ends to his wrestling career, he thought it would take something

pretty remarkable to change things now.