Idly listening to Front Row on Radio 4 last week, I heard its presenter, Tom Sutcliffe, talking to the archaeologist Mike Pitts about the new Hieroglyphs show at the British Museum. Sutcliffe was saying that he wondered if the

museum weren’t sending a subtle message about retaining at least one of its most famous – and infamously looted by Napoleon’s troops – artefacts, to wit: the Rosetta Stone. Apparently, in one of the info-screeds in the exhibition, the point is made that there are more than 100 examples of such translation stones, where the same inscription is written in other scripts as well as hieroglyphs, enabling the latter’s translation.

Pitts said – so far as I can recall, even the very recent past is such a slippery realm – that he wished the museum would be a little less subtle, that they were engaged in excellent outreach work, and that – for example – they

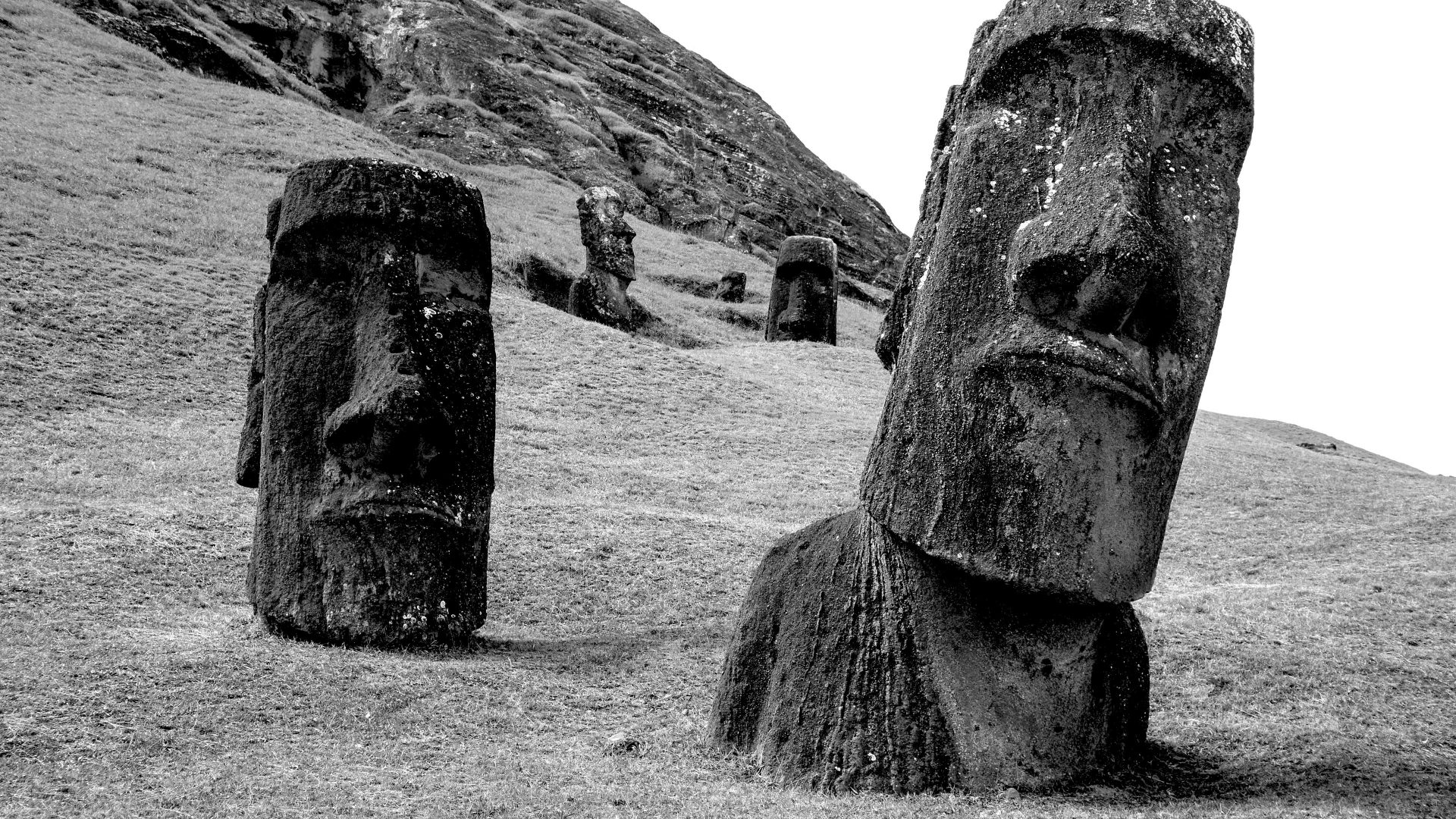

were involved in a project with local people on Easter Island concerning the moai (giant sculptured head) that they retain in their collection. Then there was some further talk about the disastrous fire there had been at the quarry beside the Rano Raraku volcano, which is where these extraordinary statues were first hewn. Pitts said he hoped the fire wasn’t actually as bad as reported – but, the implication was, these events proved the necessity of conservators from all over the world being involved in the preservation and explication of such important artefacts.

But then he would say that, wouldn’t he? I remember meeting Pitts years ago when I was writing a piece on the latest iteration of the highly remunerative theme park run by English Heritage called “Stonehenge”. I liked him – and liked his nominative determinism: an archaeologist called “Pitts”, you couldn’t make that up; but I did think he represented the somewhat troubling alliance between exhibitors and expositors, whereby the latter spin exciting yarns hypothesising how things came to be, and the former use them to generate footfall. After all, as Pitts admitted to me at the time, in the final analysis, no one can be entirely sure what the megaliths on Salisbury Plain were for.

By contrast, we have a reasonable idea of what the moai were for, because despite the terrible deracination of the Rapanui (Easter Islanders) since the arrival of Europeans in their Pacific Ocean fastness – including an episode of outright slavery when the bulk of the population were hauled off to Chile – there is a continuous folk memory concerning the statues’ erection, purpose, and the consequent environmental depredations. I went to see this storied isle for myself in the early 2000s and learnt all about how this ancient Polynesian society was brought to its knees by competitive statue-building.

Were the moai built, in part, to ward off the Europeans? This we don’t know – although some have pictograms of four-masted sailing ships incised on their mighty breasts, it seems unlikely: they were set up to face into the island’s hinterland rather than out to sea, and were erected in the centuries immediately preceding European contact, not subsequent to it. That they were built competitively, with individual clans struggling to hew, carve, then erect the biggest and most resplendent (complete with obsidian eyes), we do know – and it’s this competitiveness that led to the environmental devastation of the island, as more and more trees were chopped down to make the necessary rollers in order to transport the statues from the quarry.

It’s this quarry – where unfinished moai still lie, half-cut from their womb-like rock chambers – that the fire swept through; so, I suspect the damage – contra whatever Pitts wishes for – has been considerable. The fire may have

been started deliberately or accidentally, but that it was able to spread so rapidly and devastatingly is, once again, a function of an environmental crisis – but a global rather than a local one. Once they’d chopped down all their giant palms to make moai-rollers, the Rapanui – once mighty mariners – were unable to leave their island fastness and when the Europeans arrived, they toppled their impotent stone gods. Now humanity, collectively, has burnt all the carboniferous residuum of ancient woodlands, and we’re beginning to realise (unless we’re Bezos, Musk or Branson) that our machine-dreams of colonising other worlds were just that.

So, it seems to me surpassing ironic that the tragedy of the Rapanui and their extraordinary statues should now be farcically repeated. Perhaps, contra what Mike Pitts says, far from seeking to connect with other peoples and interpret their culture for them, we should look to the mighty stone edifices – from Martello towers to contemporary military installations – that ring our island fastness, and acknowledge that they, too, have failed to protect our culture from its inevitable decline… and fall.