“From a sort of indolence of mind, from some inexplicable terror of written thought, from I know not what weariness even before beginning – I do not read.”

This was quite an admission from one of France’s most successful authors. That he made it during his acceptance address on admission to the Académie Française in 1892 marks out Pierre Loti, one of France’s most successful authors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as someone who didn’t exactly play by the rules of the literati.

Anatole France called him the “sublime illiterate”. A young Marcel Proust loved Loti’s first novel Aziyadé so much he could recite long passages from memory. Sarah Bernhardt would alter her schedule to dine with him whenever she learned he was close by. Yet, despite his literary success and celebrity, Loti never gave up the naval career that inspired his early novels, spending relatively little time in France and even less among his peers in the salons of Paris. Even the news of his acceptance to the Académie took weeks to deliver and was waiting for him when his ship docked at Algiers.

Loti is rarely read now and is far from a household name, especially outside France. His novels were notoriously difficult to translate, their simple, repetitive, assonant style that drew the reader into his exotic landscapes and tableaux almost impossible to reproduce effectively in other languages.

On the page he was as confident and assured as he was at the lectern that day in 1892, even using part of his speech to criticise the “naturalist” school of literature popular at the time and its main exponent, Emile Zola, in particular, who was sitting in the audience.

Yet, away from the pen and the stage, Loti was a wholly different character, never comfortable in himself, always seeking a new identity, constantly reinventing, never finding a persona in whom he could be wholly content. Even his name was an invention, Pierre Loti being the pen name and literary persona of Lieutenant Louis Marie-Julien Viaud.

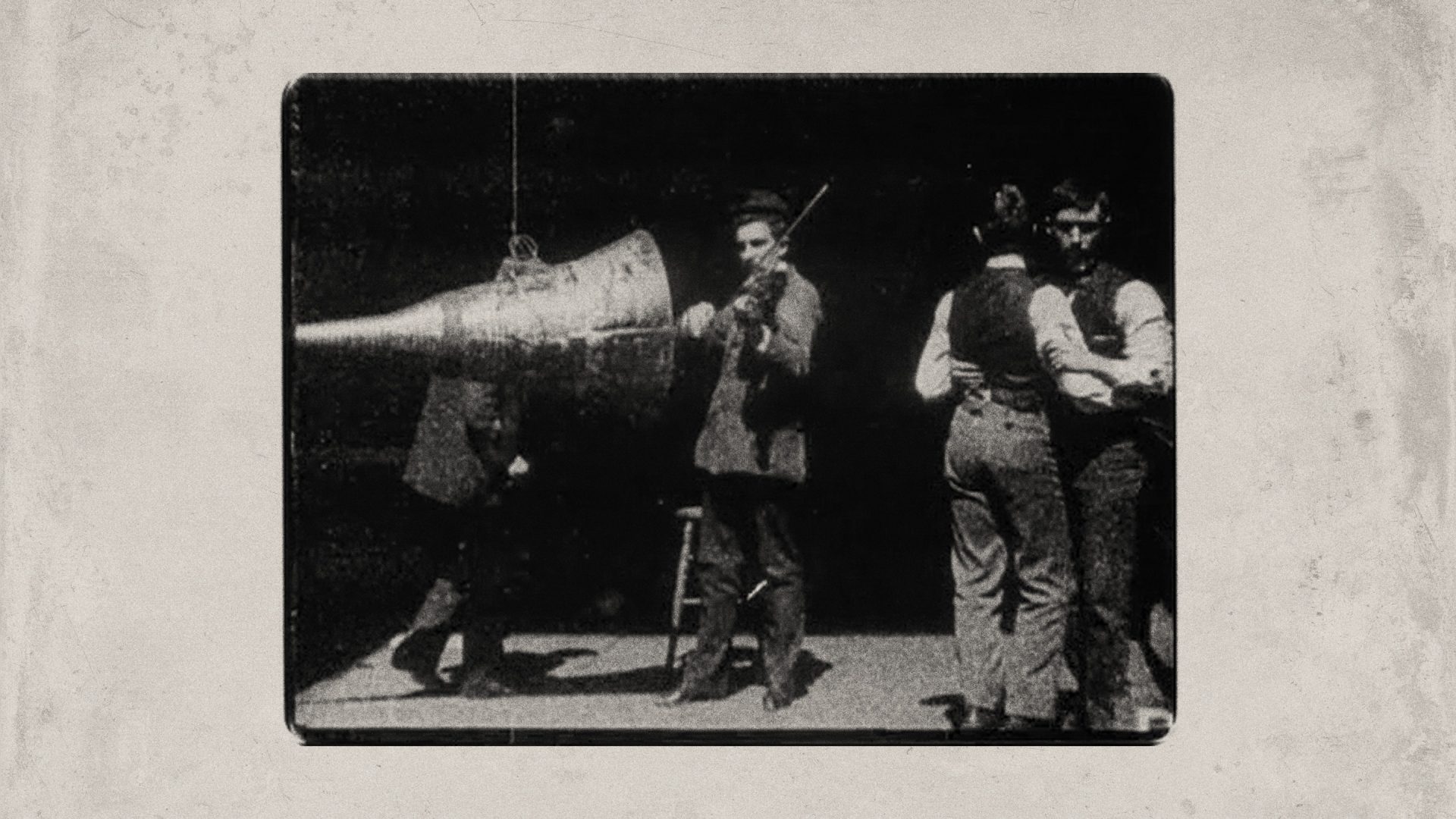

His evolving personas, influenced by his life of global travel, often meant the adoption of elaborate costumes from Asia and the Middle East in which he particularly loved being photographed. Bernhardt recalled that at their first two meetings, Loti arrived dressed in first traditional Japanese, then Turkish attire. Ahead of their third meeting, she asked if he might just come dressed as a 19th-century Frenchman.

Louis Viaud was born into an ancient family of Huguenots, the youngest of three children by 14 years. His elder brother was a naval surgeon and it was his gift of a picture book of stories from Polynesia that fired a desire to see the world in the dreamy youngster. At the age of 17, two years after his brother died at sea in the Indian Ocean, Loti enrolled in the French naval school at Brest.

Within three years he’d seen action in the Franco-Prussian war but it was voyages farther afield, to north and west Africa and to South America and beyond that inspired Viaud to begin writing down stories and incidents from his naval service. In 1872 he spent several weeks in Tahiti, immersing himself in local custom and culture to the point where Queen Pomare IV bestowed on Viaud the nickname “Loti”, after a local flower.

He turned his time in Papeete into his first big literary hit, 1880’s Le Mariage de Loti. Although clearly autobiographical and the title containing his pen name, the enigma of Loti saw to it that the character based on Louis Viaud was an English officer named Harry Grant, with the world he creates and the people in it based on the author’s deep immersion in Tahitian culture.

His naval career was a steady and unspectacular one, other than the year’s suspension he received for detailing in the pages of Le Figaro some of the atrocities he’d witnessed committed by French soldiers at the Battle of Thuận An in North Vietnam in 1883. The fictions he conjured from his travels, however, were vivid and extraordinary, transporting readers to remarkable places evoked in beautiful prose.

It was as if he were writing a version of himself, that Pierre Loti was the person he wished Louis Viaud could be, living the life he wished he could live. Yet the stories he created were all based on his own experiences – his 1879 debut novel Aziyadé, set in an Istanbul harem, emerging from a love affair on which he had embarked while stationed in Turkey, for example.

In 1886 came his masterpiece, Pêcheur d’Islande (Iceland Fisherman), a melancholy love story set in Paimpol in northern Brittany that captured perfectly the landscape and life of the Breton coast as well as the hardships of the fishermen who would sail north at the start of each summer for the fishing grounds off Iceland and remain there until the autumn – a hugely dangerous occupation that brought great apprehension to a village counting the boats home, praying none had been lost.

“Almost a flawless book and the man who wrote it is a great writer,” was the Guardian’s verdict in 1891 on the publication of the first English translation, while the Telegraph, amazed that a man not raised in literary salons with metropolitan connections, saluted “a singular example of the untrained mind, of an intelligence allowed to develop itself in its own fashion”.

While Loti’s unorthodox passage through his literary career was a contributory factor, it’s hard to define the secret of his immense success. He was writing at a time when interest in the exotic, to European eyes at least, parts of the world such as the Pacific islands and south-east Asia was at its height. Indeed, it was most likely the locations, from exotic evocations of Istanbul to the dark, menacing seas off the coast of Greenland, that made Loti’s novels so popular. Plot and character were usually way behind an evocation of setting, superficially drawn and without a great deal in the way of narrative drive. Considered individually the component parts of Loti’s fiction were flawed, but when combined between the covers of his books they somehow sang in a harmony that captivated readers in their many thousands.

These were no tubthumping advocations of European imperialism either. While Loti’s naval service made him an instrument of colonialism up until his 60s when he volunteered unsuccessfully to serve in the first world war, and his work is littered with stereotypes, the books are infused with a rare and genuine affection for the cultures he visited. Indeed, the overriding atmosphere of Loti’s output is one of a lost innocence, a yearning nostalgia for a world before the corrupting influence of Europe and an unfulfilled search for somewhere for Louis Viaud to belong.

Never able to find happiness in himself, Pierre Loti was Viaud’s attempt to make sense of the ever-present doubt that travelled wherever he did, as if the words that flowed from his pen on to paper may one day provide answers to questions he didn’t even know he was asking.