“Are the rest of you ready? Go ahead…” are the words that can be heard, very faint and crackly, immediately before the first film to synchronise live sound and vision begins. Long thought to be lost, the film was rediscovered in the 1990s and fully restored at the beginning of this century. It deserves to be widely seen – which is lucky, because now, courtesy of YouTube, it can. Entitled by its restorers The Dickson Experimental Sound Film, the 17-second clip was made by William Dickson, when he worked at Thomas Edison’s Black Maria, the inventor’s film studio in New Jersey.

Which should give you some idea of just how early the film is. We can’t be absolutely certain, but Dickson set up his camera and wax-cylinder sound recorder either sometime late in 1894, or possibly early in 1895. The aim was to produce a film that could be shown using Edison’s kinetophone: a proto-sound film system that, while not able to show integrated visual and audio tracks, nonetheless attempted to synchronise film and sound recordings.

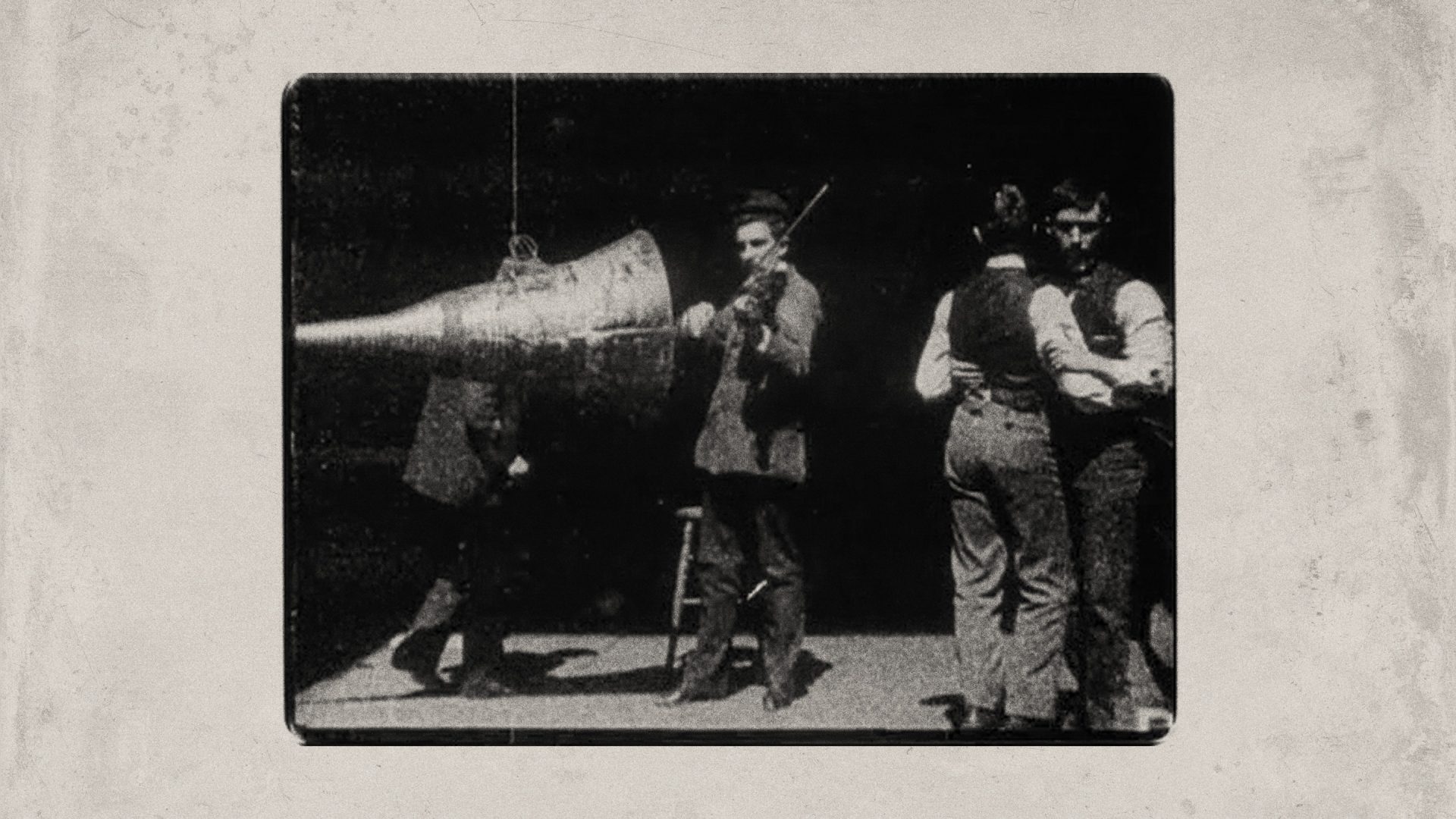

Dickson is the man in the film playing the violin into the huge horn of the wax-cylinder recorder. Three others appear: one walking across the back of the set in the closing seconds, and two others who dance together to the tune Dickson is playing. It’s these dancing men who’ve given this extraordinary moving-postcard-from-the-past its alternative title: The Gay Brothers. The reason being the apparently homoerotic intimacy with which the two revolve in each other’s embrace.

Of course, many have been quick to observe that this is an interpretation placed on the film by modern eyes: there was nothing that unusual about men dancing together in the America of the 1890s – all-male dances were a feature of a society where gender segregation was far more widespread, and nobody viewed men who attended them as necessarily homosexuals, any more than they perceived women who danced together as necessarily lesbians.

The trouble with this view is that it, too, is a modern interpretation – and one that the film itself, I’d argue, flatly contradicts. Have a look for yourself. As to why anyone would seek to deny that this is an act of frolicsome – and consensual – frottage, I’d argue that it’s for the same reason that Dickson’s film isn’t widely known outside of what we must, perforce, call the film studies community. Just as we moderns want social progress to be linear, with each new liberation of one or other formerly benighted group proceeding ineluctably from that of the one which preceded it, so we have a problem with understanding that technological progress is also discontinuous.

I mean, come on! A sound film in 1894! Louis Le Prince’s two-second-long Roundhay Garden Scene – widely believed to be the first full-motion film ever – was only made six years earlier. There are other examples of technological discontinuities – in the sense of developments that seem either to have been too in advance, or lagging behind. A couple of my favourites are the first fax to be sent (1922), and the comparative tardiness with which the fountain pen arrived on the scene.

There’s evidence of prototypical fountain pens going all the way back to first millennium China, and many scholars believe that Da Vinci developed his own, since his notebooks show none of the fading in and out you get with texts written using dipper pens. But it wasn’t until the 1880s that the innovations were in place that allowed for the first commercially viable and widely used fountain pens, which was around the same time that its effective replacement, the typewriter, began to be widely used as well.

We want technology to be developed in a logical fashion because we want to believe we, ourselves, are logical problem-solvers rather than mere tinkerers, messing about with this and that in the hope of coming up with something useful.

And by the same token, we want female emancipation to follow that of Catholics and Jews, and to be followed in turn by that of black people, gay people and now trans ones as well, because such a view bestows a Panglossian mantle upon us: all is the for the best in the best of all possible worlds – which happens to be our one.

The truth is surely far more disturbing; and just as the human species is now in grave danger from a still largely unacknowledged – if not entirely unforeseen – consequence of its techno-tinkering, so despite almost everyone’s professed intentions, the sunny uplands of inclusivity are being overshadowed by rampant bigotry and intolerance. In such parlous circumstances, it’s salutary to look upon those dancing men, seemingly quite oblivious of the darkness to come.