It was 4pm when they finally forced the door.

When the Zweigs’ servant had received no response to her knocks at 8am that morning in February 1942 she assumed the couple were sleeping late. They were still adjusting to their recent move to the Brazilian town of Petrópolis in the hills north of Rio de Janeiro where the unfamiliar heat and humidity often kept them awake late into the night. When there was still no sign of the couple by late afternoon she became concerned enough to ask a neighbour to put his shoulder to the door.

Stefan and Lotte Zweig were lying on the bed. He was on his back with his hands clasped on his stomach, dressed in a suit. Lotte was lying on her side against him wearing a kimono, her head on his shoulder, her left hand on top of his. On their respective nightstands stood the empty glasses from which they had drunk the massive doses of barbiturates that killed them.

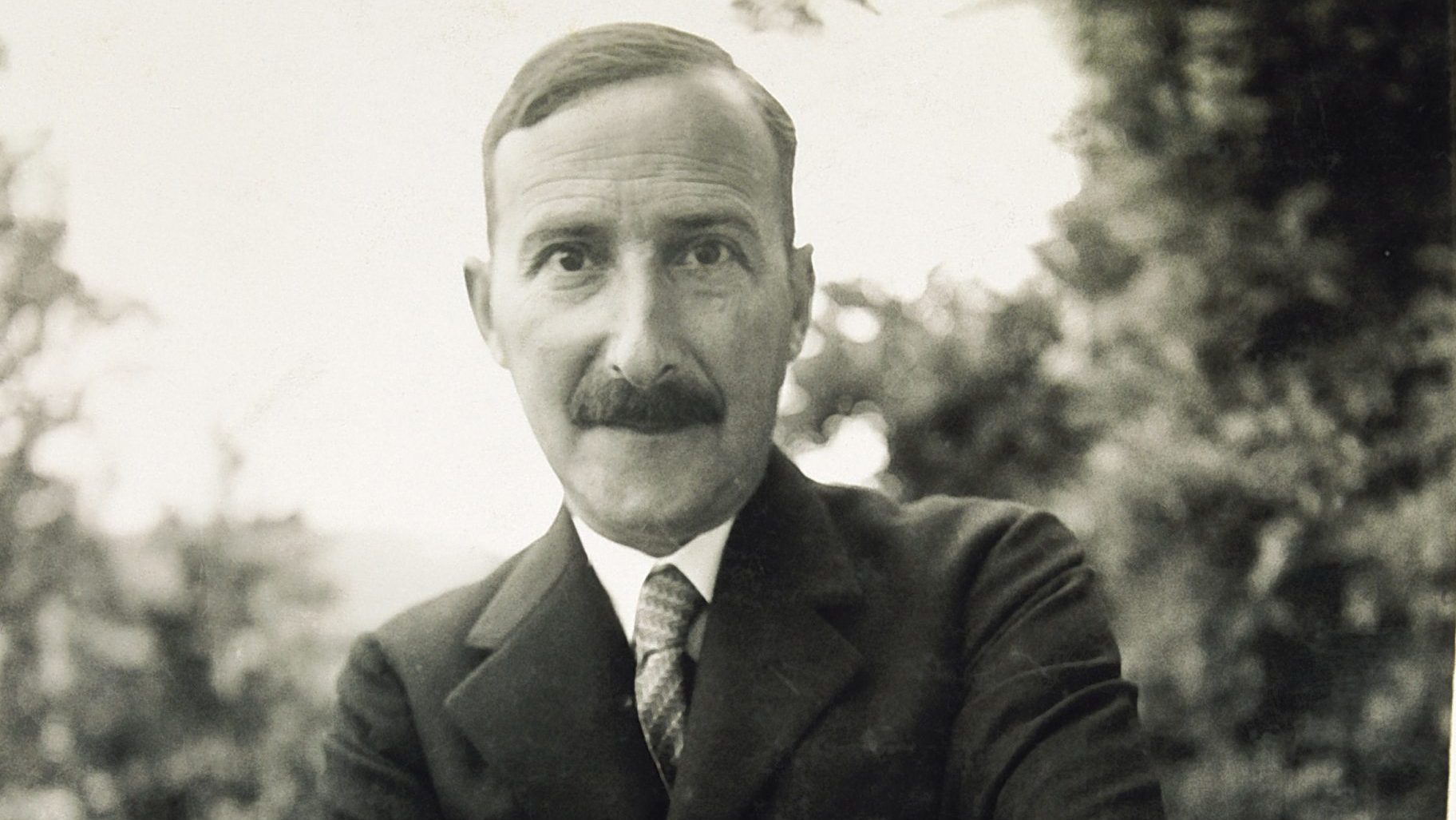

Propped up on the writing desk was an envelope containing Stefan Zweig’s suicide note. Citing his age – he had just turned 60 – the Austrian writer explained that “it would require immense strength to reconstruct my life, and my energy is exhausted by long years of peregrination as one without a country”.

His death was headline news across the world, making the front page of the New York Times and the London Daily Telegraph. Europe had lost one of its great writers and great chroniclers, a man who for the previous 20 years had been one of the most prolific and most widely translated of its authors.

Yet for the last decade, since the rise of fascism, Zweig had become a perpetual exile moving between nations and continents while longing for a return to the Viennese life he once knew. In 1942 the second world war seemed to be going Germany’s way, meaning Zweig faced the prospect of never being able to return home, of living in perpetual exile.

“The world of my own language sank and was lost to me,” he wrote, “and my spiritual homeland, Europe, destroyed itself.”

Many exiled European writers embraced their situation, energised by the injustice of their displacement, but for Zweig the loss of his nation represented the loss of his identity, commencing an inexorable erasure at the core of his being.

The day before he died he had posted the completed manuscript of his memoir The World of Yesterday to his publisher, an elegy for lost Mitteleuropa that has become arguably his greatest legacy. Although written as autobiography, Zweig saw his role more as the operator of a projector showing slides of the old Vienna he loved, a thriving, fizzingly creative city that was not only safe for Jews and outsiders but was keen to see them flourish.

The World of Yesterday showed that as well as being adrift in the world, Zweig was lost in time. He wrote of an age already long gone, of ocean liners and cafe society, of a cultural blossoming that thrived on meritocracy, unity and compassion. Even his fiction was stylistically outdated, plot-driven to the point of melodrama and written in a sentimental style already out of fashion even when he left Austria in 1934.

The dawning of his seventh decade confirmed to Zweig that the past was only slipping further away; the tolerant, diverse, creatively exciting Europe that made him growing ever more distant. With The World of Yesterday he could at least immortalise the past for which he yearned. The World of Yesterday would be his parting gift, a nostalgic testament wrapped around what we hoped would serve as a warning against complacency for future generations. Look what we had. Look what we lost.

The beneficiary of a privileged upbringing, Zweig established himself first among the cultural elite of Vienna, then a wider Europe beyond. Travelling widely through the continent, he wrote libretti for Richard Strauss, forged friendships with the likes of Romain Rolland, Rainer Maria Rilke and Sigmund Freud and corresponded with a range of European luminaries from WB Yeats to Rodin. He published prolifically, producing a string of novellas and carving a lucrative niche as an erudite biographer of historical figures; obituaries cited books about Mary, Queen of Scots and Marie Antoinette as his best-known works.

He was also an avid collector, assembling memorabilia from Beethoven’s writing desk to original manuscripts by Goethe, as if attempting to preserve the high culture of Europe while advancing it with his own writing.

As a Jewish writer, his books were among the first banned when Hitler came to power in Germany, while even before the Anschluss the far-right grew to wield powerful influence in Austria resulting in the 1934 burning of Zweig’s books on the streets of his homeland. When the police arrived at his home ostensibly to search it for weapons, Zweig realised what was coming, packed his bags and departed for London.

He moved to Bath in the spring of 1939 – a city that “reflects more faithfully and impressively than any other in England a more peaceful century, the eighteenth, to the reposed eye” – where, having left his first wife Friderike he married Lotte, his secretary, three days after Britain declared war on Germany.

The war meant that overnight Zweig was transformed from refugee to “enemy alien” and while never interned he was forced to wade almost daily through thick jungles of bureaucracy. He even needed a stack of documents just to take the train to London to give a eulogy at Freud’s funeral.

When the threat of German invasion loomed large in 1940 the Zweigs headed for New York where they joined thousands of other displaced Europeans. With the fate of their continent the only topic of conversation and the conclusions drawn being gloomy ones, Zweig moved on again, to Brazil, of which he had fond memories from a reading tour a few years earlier.

Within months, however, it was clear that this fresh start was a false start, bringing to an end this most European of lives in an uncomfortably humid rented house on a continent far from home.

The Zweigs were given a state funeral by the Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas, spotting an international PR opportunity, their caskets paraded through streets lined with people and interred close to Brazil’s former royal family. A day later a friend received a letter Zweig had posted in his final hours, asking that his and Lotte’s funerals “should be as modest and private as possible”.

Even in death, Stefan Zweig’s world of yesterday was no longer his own.