Someone must have been spreading lies about Will S, for without having done anything wrong, he was arrested one fine morning… OK, not actually arrested – but I’ve received a letter from the authorities informing me in no uncertain terms that I am “UNDER INVESTIGATION”. My putative crime? Why, watching television, of course.

Not that I’ve done it, you understand… No, really, I swear… I was only hanging on to TV at all for the feel-sick Kardashians and the feel-replete Great British Bake Off, but the truth is these tastes had become nauseatingly gourmand: there’s no such thing as “so bad it’s good” people – in the Britain of 2024 there’s only so bad it’s… criminal.

I’ve written before in these pages about the Kafkaesque outsourcing of the inexorably petty and soul-destroying bureaucracy, typical equally of state, and corporate, under late neoliberalism, nowadays. Josef K would have to accuse, arrest, and even arbitrarily punish himself by unticking the relevant boxes in the pop-up screen.

This is the trial of modern life – one extensively foretold by the futurologists of the last century. Contemplating the stentorian notice of my investigation, I thought of Ray Bradbury’s pedestrian, who, in his story of the same name, is stopped by the robot police for suspiciously walking the city streets at night, instead of staying at home in front of the box like everyone else. Worse still, when questioned by the automated law-enforcement function, the pedestrian states his occupation as “writer”; and since no one reads in the civilization of 2053, he becomes doubly suspect.

Or there’s Philip K Dick’s extraordinary 1956 story, The Minority Report, in which mutants possessed of prescience function as “precogs” for the police; and, rather like the TV Licensing Authority, scry out who’s going to commit a crime before they’ve actually done so. Both Bradbury and Dick were responding to the Red Scare in the US, and the growing collective sense during these years, that under pressure of imminent nuclear conflict, all forms of autonomy on both sides of the Iron Curtain were being rapidly corroded.

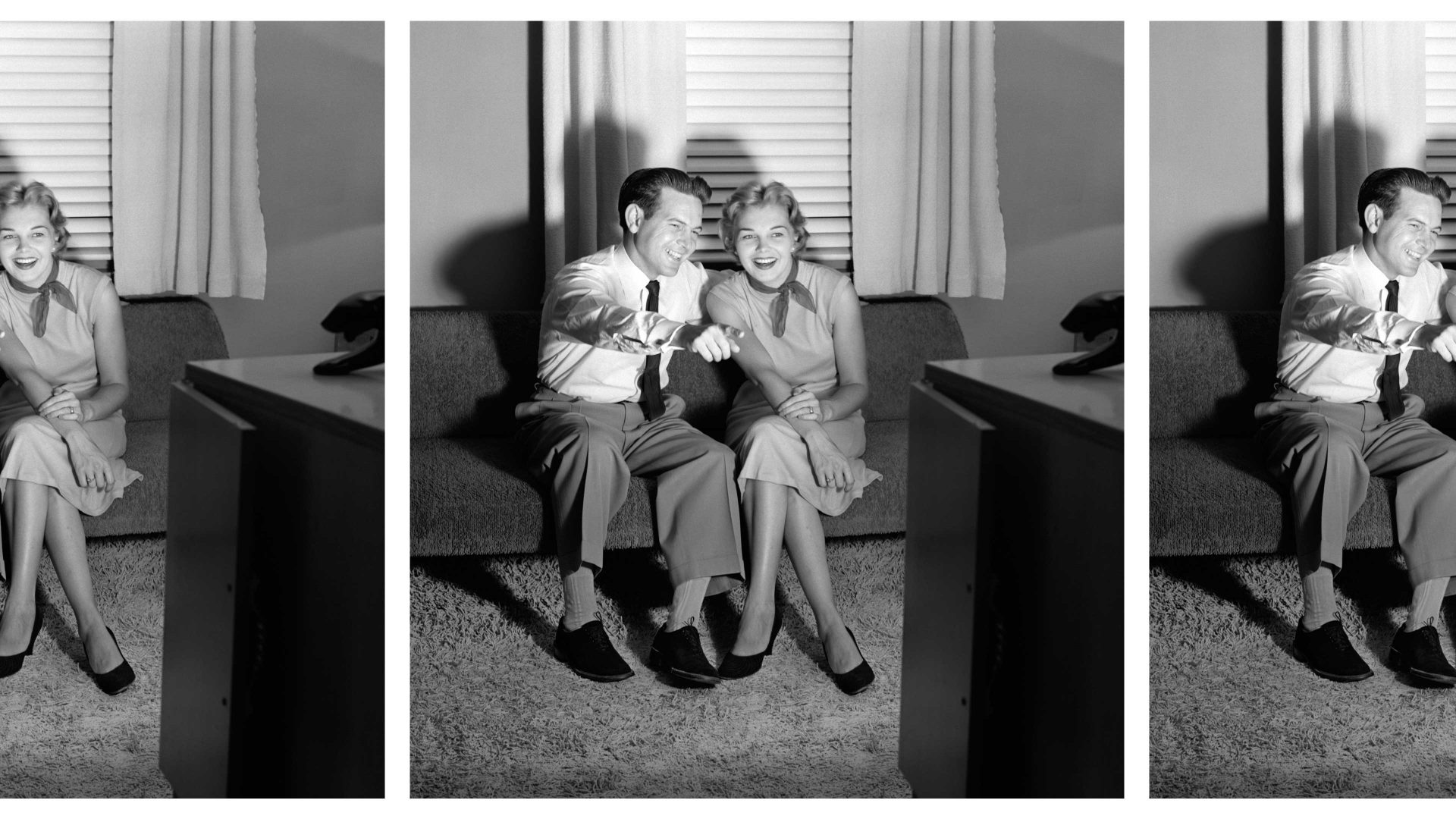

But really, television can be quite as totalitarian as, um, Marxist-Leninism. At any rate, for decades the medium exerted a totalising capability of the British collective psyche: its message was conformity to old school ideologies – Queen, country, sexist, racist and homophobic sitcoms – just as the message of new ones is reality on the instalment plan: buy now – pay later. Once upon a time, everyone went to the cinema then stood afterwards and sang the National Anthem; by the early 1960s, when television ownership was almost universal, everyone watched television – and a lot of it. Entire multi-generational families, sitting there in a biosphere of their own brassica-induced afflatus, watching Bernie gently insert his bolt, or the Graham Kerr vault over the breakfast counter in too-tight Terylene trews.

To not watch television under such circumstances was, indeed, unthinkable – quite possibly to the point of criminality. But nowadays, when every internet-enabled device with a screen spews imagery forth, and every half hour or so the big streaming services ejaculate ten thousand newer – and duffer plot lines – to arc across these myriad minuscule empyreans, there’s really no need for even the most senescent long-term care home resident to witness Fiona Bruce filching priceless heirlooms from their conspecifics who’re still at liberty.

No: everyone must die – and so must broadcast TV, and quite possibly with it the hectoring state broadcaster must also die away in a staticky susurrus; to be replaced, no doubt, with wholly corporate data services that fully integrate the commodity with civic space, such that we all wander around in one of those duff, 2010 iPad-influenced CGI sequences, where everyone is wiping the air’s arse to summon up floating images of as yet uncommitted crimes.

While the only antique road I’m interested in being shown is the one that runs by the end of my own, and which once connected Roman Londinium to the ironworks in the Sussex Weald. Lying, sleepless, last night, and contemplating a near-criminal night walk; I wondered at the identity of my investigating officer. The Authority will have an automated system that chases those delinquent citizens who, like me, are so revolted by the dross the passes for entertainment in this day and age we haven’t renewed our licences – but presumably, once the INVESTIGATION gets underway, like some erstwhile East German dissident, I’ll be assigned my own case officer.

I picture this fellow as rather like the Stasi spy in the superb Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others): a weedy, bat-eared, painfully-shy introvert whose only sexual relationships are with prostitutes, and who spends his entire working life watching gregarious, muscular, neat-featured me; who, in turn, isn’t watching television.