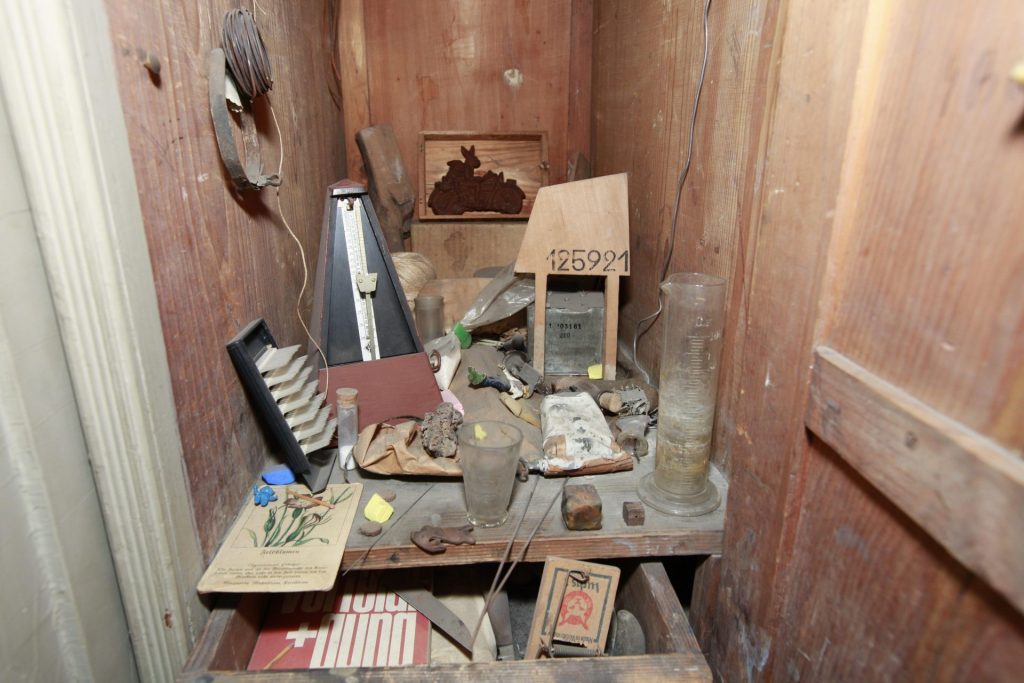

Despite a controversial renovation in 2007-2014, the Block Beuys section in Darmstadt’s Hessisches Landesmuseum retains its atmosphere of quiet decay, the cryptic and apparently provisionally stowed piles of materials that clutter its rooms bringing a restlessness to the place, rather like some unquiet grave.

Installed by Joseph Beuys himself, beginning in 1970, the beige, browns and greys so redolent of that era are carried in enigmatic – or arguably just nonsensical – arrangements of fat, felt, copper and dust: a pile of felt sheets; odd arrangements of electrical equipment and dried out sausages; a wedge of solidified, yellowing fat.

It’s a suitably unsettling memorial to Germany’s best-known, and perhaps most important artist of the post-war period. A sculptor, political and environmental activist and self-styled shaman, Joseph Beuys believed in the power of art to transform society, and with his notion of “social sculpture”, he expanded the boundaries of art to include all human endeavour.

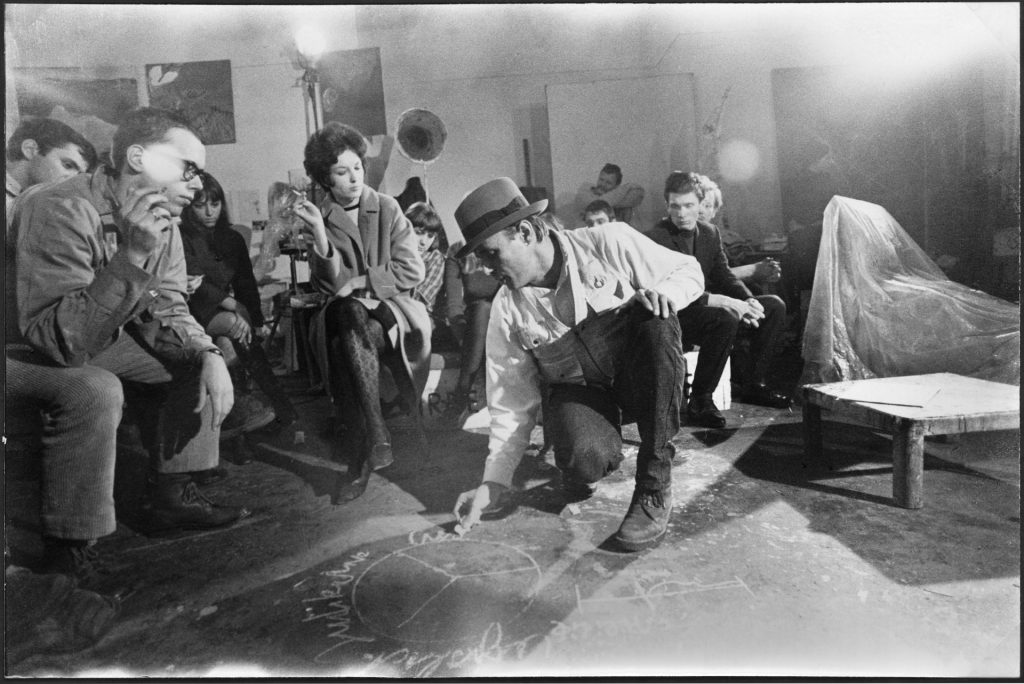

As West Germany began to reconcile its fascist past with a future centred on industry and commercial success, Beuys was a disruptive presence, his war service and later associations with former Nazis leading one critic to label him “the eternal Hitler youth”. In his fisherman’s jacket and fedora he presented an idiosyncratic alternative to contemporary superstars like John Lennon and Bob Dylan, provoking rage and adoration in equal measure: “Just as Lennon could imagine being more popular than Christ”, writes the art historian Mark Rosenthal, “Beuys made the same comparison in some of his Aktionen, or ‘Actions’, in which his flair for the dramatic abounds.”

Marking 100 years since his birth, the celebratory events and exhibitions held this year in Germany and beyond show that the man and his work are as contentious and influential as ever. In the artist’s home state of North Rhine-Westphalia, forthcoming exhibitions such as Ticket to the Future at the Kunstmuseum Bonn, Beuys & Duchamp: Artists of the Future at the Kunstmuseen Krefeld, and Technoshamanism at the Hartware MedienKunstVerein, Dortmund, indicate his continued significance to artists today, and the scope for new research into his work.

Beuys died on January 23, 1986, aged 64, his absence contributing no doubt to the mausoleum-like atmosphere of Block Beuys, which retains the presence of its creator much like a discarded chrysalis evokes its former occupant. “No other contemporary artist, not even Andy Warhol, was so personally a part of his works as Beuys”, wrote the German critic Bernhard Schulz in 2013: “With none did death so call into question the very survival of their oeuvre.”

That life and art merged in Beuys’s imagination, is amply illustrated in his fictional Life Course /Work Course, published in 1964, in which biographical details real and imagined are expressed as a series of artistic statements. His birth in 1921 is described as an “Exhibition of a wound drawn together with plaster”, his mental health crisis of the mid-1950s recorded as “working in the fields”.

Beuys notes his appointment as professor of sculpture at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in 1961, the same year that he “adds two chapters to Ulysses at James Joyce’s request”. Against 1964, Beuys records his recommendation “that the Berlin Wall be heightened by 5cm (better proportions!)”, a provocation that jeopardised his teaching position and prompted an investigation by the North Rhine-Westphalia Department of the Interior.

In his defence, Beuys protested: “It is surely permissible to contemplate the Berlin Wall from an angle that takes only its proportions into account. This defuses the Wall at once. Through inner laughter. Destroys the Wall. One is no longer hung up on the physical Wall. Attention is redirected to the mental wall and how to overcome it, and surely that is the real issue.”

It’s little wonder that the art historian Benjamin Buchloh accused him of spouting “simple-minded utopian drivel”, and yet, somehow one knows what he means and perhaps it is this improbable plausibility, along with the stories he told about himself, that have kept his flame alive.

One story – ‘the Story’ as it has been termed – is of particular importance, a personal mythology in which bare facts are steeped in a mystical narrative of rebirth and redemption.

As a pilot in the Luftwaffe during the Second World War, Beuys was shot down over Crimea in 1944: this much is true. But Beuys claimed that he was rescued from the wreckage by nomadic Tartars, who nursed him back to health, before he regained consciousness 12 days later in a German military hospital.

In 1978 he told the art critic Caroline Tisdall: “I was completely buried in the snow. That’s how the Tartars found me days later. I remember voices saying “Voda” (‘Water’), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep the warmth in.”

The Story is now known to be almost entirely untrue, but its characterisation by commentators as, variously, a response to trauma, artistic self-mythologising, and an abject lie, are measure of the spectrum of feelings he provokes to this day.

For Beuys, the Story served as the basis for his work and artistic persona: fat and felt became profoundly (if obscurely) meaningful materials, that recurred as frequently as the underlying narrative of transformation and rebirth. His Actions and cryptic pronouncements, not to mention the many bizarre objects he gathered and created, invoke the rituals of non-industrial cultures, pitting them against the values and assumptions of the rational West.

For many, the Story was and remains deeply troubling, his supposed spiritual as well as physical healing by the Tartars implying that he had been absolved of his actions in the service of the Nazis. The stain of Nazism combined with Beuys’ apparently magnetic personality to explosive effect in an early Action at the Aachen Festival of New Art in 1964, an event organised by leading figures of Fluxus in Europe. Fluxus was an international avant-garde movement with its roots in the New York new music scene. It centred on the composer John Cage, and included in its orbit figures such as Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik, who broadly sought to democratise art by removing it from the museum context and allowing chance occurrences and audience participation to shape it.

The festival was held on the 20th July 1964, the 20th anniversary of the attempted assassination of Hitler, and included performance pieces by a number of artists who made references to the Second World War. Accounts of the performance vary somewhat, but it seems that Beuys may have been unintentionally accompanied by a recording of Goebbels’ infamous Total War speech.

At the same time, Beuys melted fat over a stove, which he poured into a mould, enraging a group of right wing students who rushed at him, and punched him in the face. Shortly afterwards Beuys was photographed with a bloody nose, holding up a crucifix, his arm raised in a salute, a gesture that unsurprisingly upset the protestors still further, but secured Beuys’ place as a figure in the public imagination.

Though Beuys continued to associate himself with Fluxus, they were less keen on him, and disapproved of his cultish following and the deeply personal, expressive nature of his performances.

One shared point of reference for Beuys and the wider Fluxus movement was the artist Marcel Duchamp, held up by Fluxus as a hero figure, but treated with considerably more ambivalence by Beuys. In 1917, Duchamp had transformed the criteria for what art could be by submitting a urinal for exhibition, and his ‘readymades’ contributed to the antiestablishment, democratising ambitions of Fluxus. But if Duchamp believed that art is whatever an artist says it is, Beuys went further: he believed “that every human is an artist, that it is about the creative principle of humans and not about the artists”.

Images

Beuys’ expressed his frustration at Duchamp in an Action broadcast live on West German television in 1964, but not recorded, in which he wrote “The Silence of Marcel Duchamp is Overrated” on a placard, which he then seems to have covered with bars of chocolate. The extended dialogue between Beuys and Duchamp is the basis of a new exhibition opening in Beuys’ birthplace, Krefeld, in which for the first time the similarities and points of divergence between the two artists are explored.

Like Duchamp, Beuys continues to resonate with artists today: in 2005 Marina Abramovic paid tribute to Beuys by reenacting his gloriously bizarre 1965 Action, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, while artists Katinka Bock, Christian Jankowski and Jon Rafman respond to Beuys in Kunstmuseum Bonn’s Ticket to the Future.

At Tate Modern in London, artists Ackroyd & Harvey have paid homage to one of Beuys’ most important and prescient works, 7000 Oaks, his 1982 project to plant 7,000 oak trees in the city of Kassel. Some 7,000 large stones were also deposited in the city, with one removed each time a tree was planted. It is a fine example of Beuys’ “social sculpture”, in which art, urban renewal and environmental change came together in one act. In 2007, Ackroyd & Harvey harvested acorns from the Kassel trees, and now 100 saplings have been brought together as a living sculpture at Tate Modern, in advance of being permanently planted next year. It’s a fitting tribute to the prescience of an artist who foresaw the climate crisis that has come to a head in his anniversary year.

More details on exhibitions marking Beuys’ centenary are at beuys2021.de/en/homepage

BEUYS WILL BE BEUYS: A LIFE IN ART

1921: Born in Krefeld; his family move to Kleve

1936: Takes part in a march organised by the Hitler Youth: participation is mandatory.

1938: Briefly runs away with a circus

1940: Volunteers for the Luftwaffe

1944: Beuys’ plane crashes over the Crimea. He is decorated with various military honours

1947: Enrols at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf to study sculpture 1948: Assists with a set of doors for Cologne Cathedral 1956: Suffers severe depression

1961: Made professor of monumental sculpture at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf

1963: At the first Fluxus festival in Düsseldorf, presents his first ‘Action’, Siberian Symphony

1964: Beuys is attacked during his Action Kukei / akopee – No! / Brown Cross / Fat Corners / Model Fat Corners; The Silence of Marcel Duchamp is Overrated is broadcast live on West German television

1965: Presents the Action How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare

1970: Block Beuys is installed and opened at the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt

1972: Beuys is dismissed from the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf

1978: Wins court case against the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf and is allowed to retain his title and studio

1980: Co-founds the Green Party

1986: Dies of a heart attack