The video clip that did the rounds in the first days of the Ukraine war tells a story, shared by many, that is anathema to Brexiteers. “Hello,” says the voice of Angela Merkel, “congratulations, we decided to take your country to the European Union!” “Oh f***! I am so happy!” says Volodymyr Zelensky, his eyes wide with excitement. Water explodes from the fountain behind him, Beethoven’s Ode to Joy begins to play and Zelensky laughs, bursting with pride. It all deflates when Merkel realises she’d meant to call Montenegro.

It’s all fake, of course – a 2015 clip from the TV comedy Servant of the People, when Zelensky was still only pretending to be the Ukrainian president. But the point is –many countries are desperate to belong to the EU club, which they see as a beacon of progress and safety.

After Russia attacked Ukraine on February 24, Zelensky applied for his country to join the EU for real, as did Moldova and Georgia, both under partial occupation by Russia. Several EU leaders, who have responded to the war with surprising unity, hailed Ukraine’s application. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said: “Ukraine is one of us and we want them in”.

But according to some calculations it could take until at least 2036 for Ukraine to join under normal procedures. Slovakia’s prime minister Eduard Heger argued for a special membership track, saying there was no time to hesitate in embracing a country “protecting our system, our values”. Many others, including Italy’s premier Mario Draghi and Austrian president Alexander Schallenberg, have called for a creative approach to the cumbersome years-long process, saying expansion was more a geostrategic instrument than just number-crunching and laws.

“The 24th of February was a watershed,” Schallenberg told the Financial Times. “We have to… use the maximum of our imagination, to not stick to the old ways, to not stick to the same template that we have used for every accession to the EU since Great Britain.”

Does this mean that the EU, after years of aversion to expansion due to multiple crises, problem members and Brexit, is ready to grow once more?

Well, yes. And no. The moral case is strong for Ukraine as its citizens die for values espoused by the EU and when Zelensky is giving a masterclass in leadership.

“The arguments of those sceptical of enlargement to these three countries look increasingly questionable on their own terms,” wrote Richard Youngs, senior fellow and EU foreign policy specialist at Carnegie Europe. Morally, “it would be cruel to rebuff Ukraine’s membership plea.”

The EU’s international leverage and credibility could hinge on what it does next. Given Russia’s opposition to Ukraine joining Nato, taking it into the western fold through the EU seems an obvious path to pursue.

To a certain extent, this seems to be happening as Von der Leyen says the EU executive should give its “opinion” on Ukraine’s membership in June. “This first step usually takes years,” German MEP David McAllister, chair of the European Parliament’s foreign affairs committee, told me. “The Commission is working to examine the applications of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia around the clock.” Ukraine is already being integrated into the single market under previous agreements.

Any move to unlock and speed up expansion would be seismic, but seismic is what is required, a former senior EU official told me. “The whole architecture of the EU has been blown up by the war,” he said. “There’s a necessity to give a response and indicate some concrete path towards redesigning Europe.”

This fits with what Draghi told European lawmakers in Strasbourg earlier this month – that the new realities required “an acceleration in the European integration process”. He said Italy supported the immediate opening of accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia (the country closest to accession), wanted the EU to move faster in talks with Serbia and Montenegro, and be more mindful of the “legitimate expectations” of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo.

But dig deeper, and it’s much more uncertain. At their summits in Versailles and Brussels, EU leaders did not offer Ukraine candidate status, nor even the lesser status of membership perspective. While collectively effusive towards Ukraine, European leaders are split. Keen Baltic and central European members are facing off against the big beasts France and Germany, plus the Netherlands, Italy and Spain – all reluctant to rip up the carefully calibrated accession rulebook of painstaking legal, regulatory and other forms of alignment, especially without first overhauling the way the bloc operates. One envisaged reform is to make the process reversible if candidates backtrack on reforms.

In one sense, caution towards accession is understandable in the context of the past decade. EU membership almost doubled this century, with 10 new countries – mainly former Soviet states – joining in 2004, Bulgaria and Romania in 2007 and Croatia in 2013. Since then the EU has been stung by bitter internal disagreements while tackling the global financial meltdown, the Eurozone and refugee crises and the horrors of Brexit.

That last nightmare is refusing to go away, with foreign secretary Liz Truss – perhaps with domestic leadership posturing in mind – threatening to tear up parts of the Brexit treaty signed by Boris Johnson in 2019 and endanger the Good Friday Agreement for peace in Northern Ireland. The attorney general, Suella Braverman, reportedly approved overriding the Northern Ireland Protocol, saying its border checks are unfairly enforced – grounds dismissed by legal experts, particularly since the implications were known from the start.

It’s a grim reminder that disputes with mischief-making countries can grow out of control and occupy headspace when bigger things, like the Ukraine war, require full attention. The EU doesn’t want any more of this. It’s still dealing with the problems that came with eastern expansion. Many believe Romania and Bulgaria joined too soon. Hungary and Poland, in breaking EU law and blocking decisions such as refugee redistribution and then using their vetoes to protect each other from sanctions, have become enormous thorns in Brussels’ side. Although the war has modified Poland’s stance, Hungary is currently blocking EU efforts to ban all Russian oil, compromising the sixth joint sanctions package and hindering the EU’s efforts to squeeze Vladimir Putin further.

There’s been no real progress with the five current candidates – the fifth is Turkey – since then-president Jean Claude Juncker said in 2014 that there would be no expansion until 2019. That year, some EU member states, including France, controversially blocked even the start of membership talks with North Macedonia and Albania.

While apparently welcomed now, Ukraine’s membership could also become problematic, not least because its size would give it high status and power. Currently Kyiv is not ready, it is high on the corruption lists and its democracy is not embedded. Taking in a country with an uncertain border with Russia could cause problems for years to come, even without Putin. The EU is still licking its wounds from allowing the accession of Cyprus without resolving its uneasy Greek-Turkish division.

Delays have dampened enthusiasm within the current candidates and allowed unrest to develop in the Western Balkans, where Russia and China are vying for influence. The new mood music in the EU is in part an act of self-preservation – let’s grab them before they go elsewhere and boost our enemies. As Schallenberg said: “There is no vacuum. It’s either our model or someone else’s.”

The patchwork of schemes, such as the neighbourhood policy, designed to expand the reach of the EU model have not really worked. The Eastern Partnership, which included Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine all but disintegrated as Belarus drifted away and Russia-backed Armenia and Turkey-backed Azerbaijan went to war. Frustrated aspirant countries fear these are little more than eternal waiting rooms where the EU fobs off those it only pretends to want.

This could be remedied if the system were redesigned to use associate membership as a stepping stone towards joining, Dr Andreas Wittkovsky of Berlin’s Centre of International Peace operations, who has worked in Kosovo, told me. “It shouldn’t be the end of the story, it shouldn’t exclude full membership.”

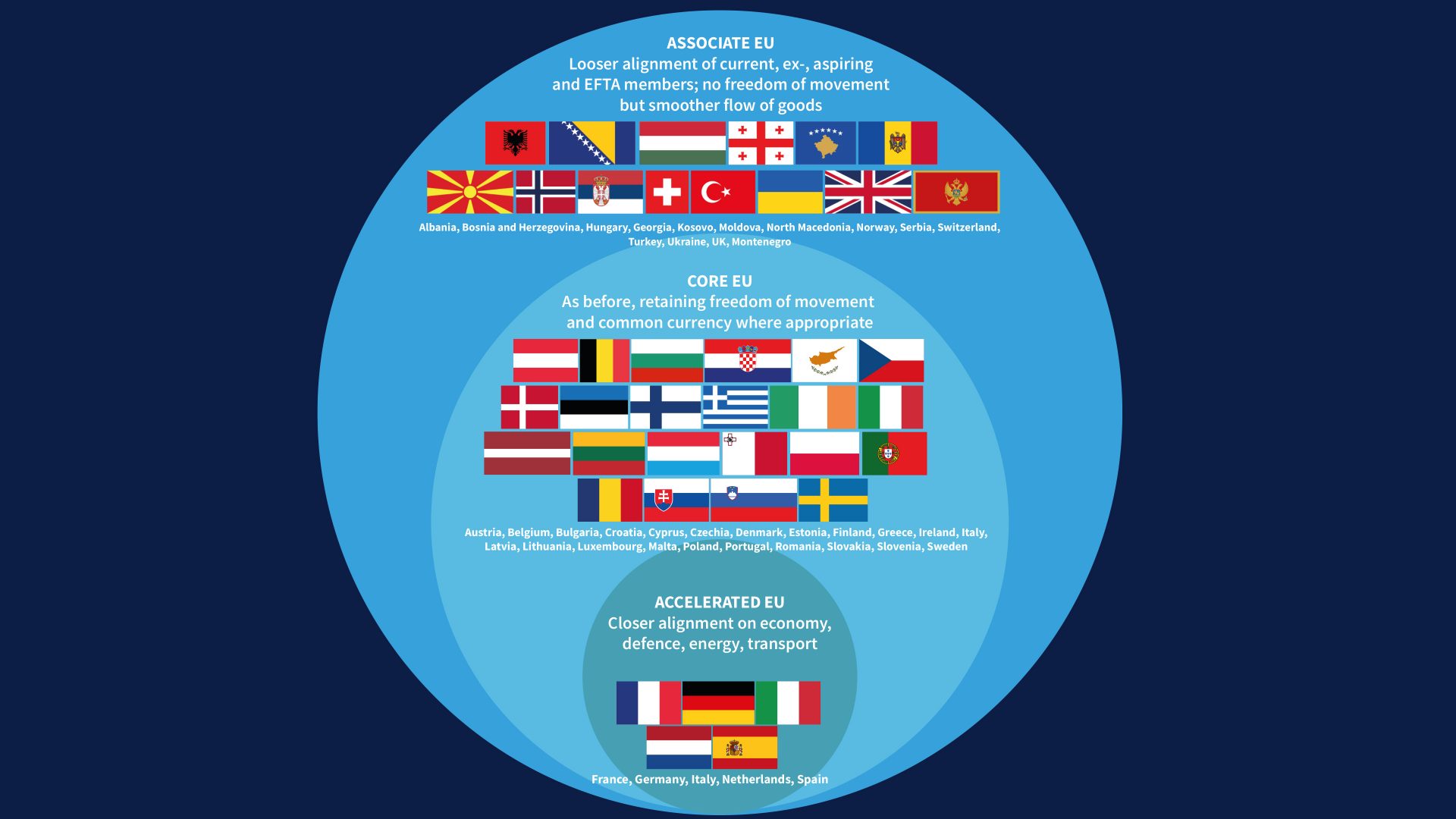

Amid the strong feeling that “something must be done”, increasingly, the idea of a multi-tier Europe, once decried as sacrilege, is being seen as a solution.

In a speech on May 9, Europe Day, French president Emmanuel Macron outlined a radical proposal to redraw the political shape of the EU with a new “European political community” that could also include and give a voice to aspirant members such as Ukraine and departed ones – a nod to the UK.

“This new European organisation would allow democratic European nations adhering to our set of values to find a new space for political cooperation, security, cooperation in energy, transport, investment, infrastructure, and the movement of people, especially our youth,” Macron said. The “legitimate aspirations” of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia “invites us to rethink our geography and the organisation of our continent.”

This idea is similar to a recent proposal by former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta for a European Confederation of 36 countries.

“This could produce a two-tier Europe or maybe a three-tier Europe,” the former EU official – a friend of Letta – said. “The European Union surrounded by a confederation and a third circle in the middle of a core number of states to take things further, to do more on economic integration, energy, the military, defence and security.”

He’s sure such ideas will be buzzing around the corridors of forthcoming EU summits, and that they could provide an opportunity to re-engage with the wayward, but politically important, Turkey, as well as reach out to Africa and the Middle East.

As for the UK, “the view in Brussels and Paris is that none of this can happen until Johnson goes,” Charles Grant, Director of the Centre for European Reform, told me. “The contempt is extraordinary – not regarded as trustworthy or reliable. Someone you can’t do business with”

If Macron’s new grand plan promotes a new spin on relationships with those outside the bloc, then Draghi’s Strasbourg speech offers a way to reshape those within it, something that could also lead to a way to embrace cantankerous members without the risk of complete chaos and deadlock.

The Italian leader urged the EU to streamline its decision-making processes by embracing “pragmatic federalism” in areas such as defence, foreign policy and the economy. He called the EU to drop the unanimity requirement for common foreign and security policy decisions. This could at a stroke remove the self-interested stranglehold members have on EU business and reduce the fear that new ones could do the same. But getting rid of unanimity would be difficult, since current voting rules mean Hungary would have to vote away its own veto.

Grant isn’t sure that the idea of the treaty change required for amending the EU rulebook has much support among members, while Macron’s idea of a breakaway inner circle could cause trouble. “It’s very controversial for an avant-garde group to go off ahead – it would be hugely divisive,” he said. “Macron is a very optimistic guy, very brave. Like (Tony) Blair he believes he can walk on water. But if he tries this it might end in tears.”

But he believes that EU members are warming to the idea of a confederation or political community as opposed to faster expansion.

It’s a tricky path, but given the changes forced by the pandemic, including joint vaccine procurement and financial tools for the recovery, the EU may finally be in a place to take a bold step to a new future.